Those who know me, have probably heard [I talk a lot about it] that I am currently working on a new history of the Iron Cross [working title: A Cultural and Combat History 1813-2008], which should be published by Greenhill Books next year. Among many other things, the book will be introducing some of the men and women who were first to be decorated with the iconic award. Triggered by a few things I had to read and see online in the past two weeks, I decided to share a little bit of the information before publication.

We know who the first winners of the Iron Cross were in 1813, in the Wars of Liberation and in 1870, during the Franco-Prussian War, but that changes radically, when we look at the third institution of the Iron Cross in 1914. While in the earlier conflicts the power to bestow the iconic award had rested solely in the hand of the King of Prussia himself, underlining its value and importance, this changed with the outbreak of war in August 1914, where due to the enormous size of the German Army, Wilhelm II placed the right to bestow the Cross into the hands of the commanders of his armies. The German Army of the First World War was a federal force, comprising the armed forces of four kingdoms (Bavaria, Prussia, Saxony and Württemberg), six grand duchies (Baden, Hesse-Darmstadt, Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Oldenburg and Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach), five duchies (Anhalt, Brunswick, Saxe-Altenburg, Saxe-Coburg-Gotha and Saxe-Meiningen), seven principalities (Lippe-Detmold, Schaumburg-Lippe, Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt, Schwarzburg-Sondershausen, Reuss Elder Line, Reuss Younger Line and Waldeck-Pyrmont) and three Free and Hanseatic Cities (Bremen, Hamburg and Lübeck). And while the sovereigns (and Senates) of each of these states, along with the Prince of formerly sovereign Hohenzollern territories in south-west Germany, had the authority to issue their own awards, the Prussian Iron Cross could and was awarded to soldiers in all those contingents, just like an ‘Imperial German’ decoration (which it never was). This resulted in decentralisation of records on a scale not seen in previous conflicts which, together with the tragic fact that the vast majority of those records were destroyed or lost in the Second World War, makes it incredibly difficult to answer the question who the first winner of the Iron Cross of 1914 actually was.

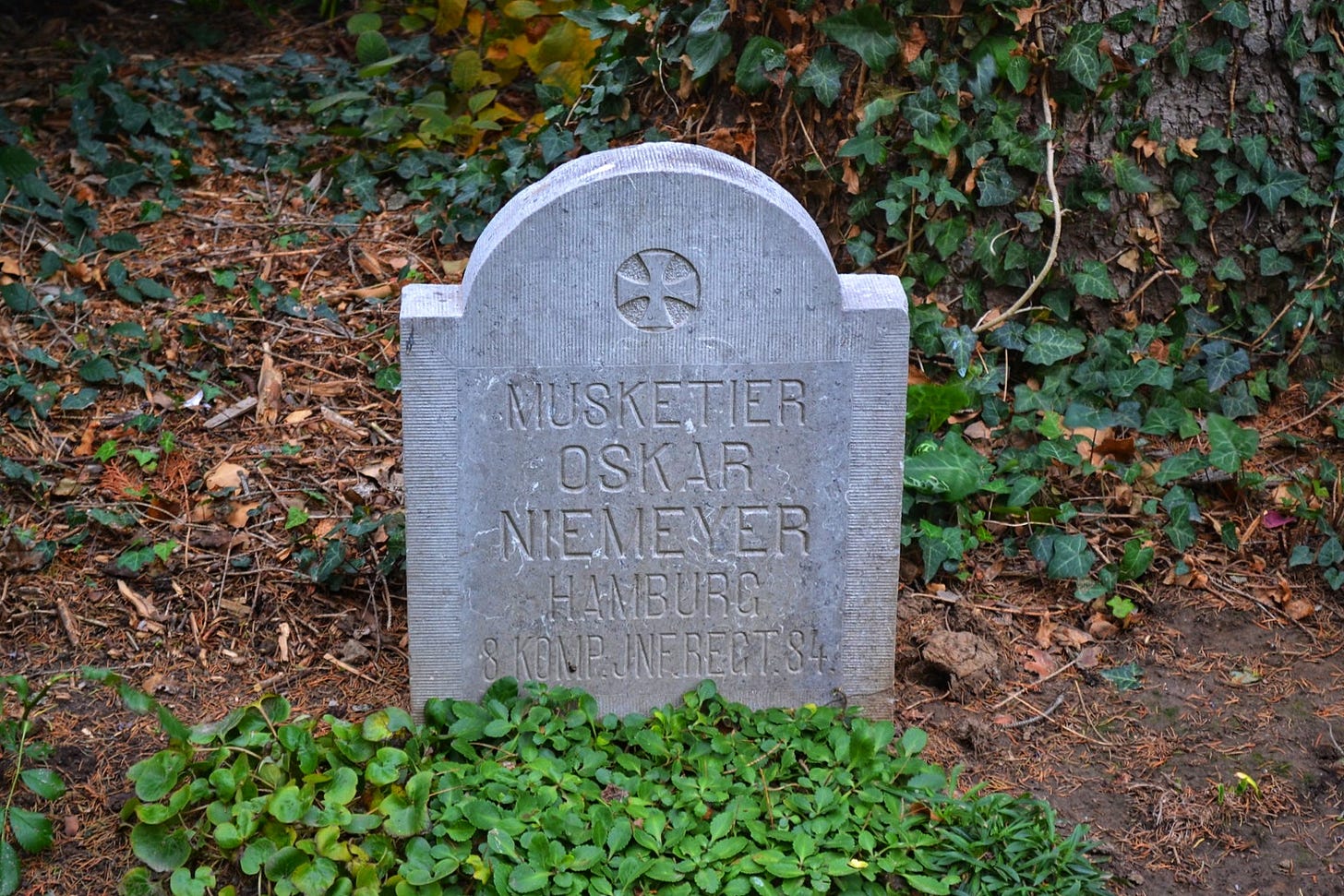

The tourist office of Mons in Belgium still claims that the first man of the German Army to win an Iron Cross (Second Class) in the First World War was Musketier Oskar Niemeyer, who today is buried on the St. Symphorien Military Cemetery, a CWGC burial ground in Saint-Symphorien in Belgium (originally a German cemetery, Ehrenfriedhof 191), which contains the graves of 284 German and 229 Commonwealth soldiers. Niemeyer’s claim to fame can also be found in several English-language books about the battle, there is a Wikipedia entry about him and the story is continuiessly being repeated in online articles, on social media platforms, in podcasts and so on. It can even be found on the website of SHAPE [Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe].

As such, Niemeyer’s grave in St. Symphorien Cemetery can often be found adorned with poppy wreaths and small wooden crosses left by (mostly British) battlefield pilgrims. Oskar Niemeyer is said to have been decorated posthumously for an extreme act of bravery, just like the British Lieutenant Maurice James Dease, who was the first officer to posthumously receive the Victoria Cross and is also buried in the cemetery.

So what evidence is there that Niemeyer was the first winner of the Iron Cross in the First World War? The short answer to this question is: None at all! But let’s look at this in a bit more detail.

HERO OF NIMY BRIDGE

On 23 August 1914, during the Battle of Mons, a patrol of 8th Company, Infanterie-Regiment ‘von Manstein’ (Schleswigsches) Nr. 84 (short 8./IR84) approached the Nimy Bridge spanning the Canal de Mons à Condé, which was heavily defended by British troops. The swing bridge had been retracted and a hail of fire was directed against the Germans from the other bank. Oskar Niemeyer’s company commander Oberleutnant Grebel, later described what happened next:

‘At first there was no sign of the enemy, who was well entrenched behind piles of sandbags on the other side of the canal. The two platoons avoided 10th Company's position as far as possible and moved furthe to the left, taking advantage of the terrain. Seeing more of our own troops to the left of his platoon as they proceeded, Vizefeldwebel Hartwig sent Unteroffizier Röver and his group out to secure his left flank. Röver advanced with his group towards the canal and discovered a swing bridge there, which had turned to the opposite bank. Then Musketier Niemeyer decided to throw himself into the canal and fetched a barge from the opposite bank. On it, the group crossed the canal despite the heavy enemy fire. From a house not far from the canal, Röver had a good view of the enemy position and was able to apply effective fire. Under the cover of this fire, Niemeyer managed to turn the bridge back to the northern bank. Unfortunately, this brave man fell shortly after his heroic deed. Niemeyer came from Hildesheim, was a gardener by trade and had joined the company as a recruit in the autumn of 1913. He was a lively, popular soldier who had always done his duty and obligation and had a great future ahead of him. The company owes a great deal to his heroic deed, for his bold action played a decisive role in the success of the attack on Nimy. Honour to his memory!’

Major Liebe, the Adjutant of IR 84 equally remembered Niemeyer’s deed:

‘The brave 10th company had lost its outstanding leader, Hauptmann Stubenrauch, who had been shot in the leg. The other companies of Battalion von Vieregge had also suffered painful losses. The enemy troops had entrenched themselves in the houses on the southern bank and on the railway embankment, held the attacking companies in check with well-aimed fire and dominated the bridge crossing. It was already evident here that the old English troupiers, hardened by colonial warfare, were good soldiers. soldiers of whom we in Germany had had quite the wrong idea. After a long firefight however, we gained the upper hand. A patrol of II/84 under Unteroffizier Röver (8th/84) succeeded in reaching the bridge over the canal. The Musketier Niemeyer of 8th company swam through the canal in spite of the fierce fire of the English and swung the bridge, which the enemy had turned away, into a closed position, so that the further crossing was made possible. The brave man suffered a heroic death in the process [of the crossing]. A monument to his heroism is hereby set up for him.’

Fahnenjunker-Unteroffizier von Zeska of 12./IR 84 also saw Niemeyer fall: ‘(...) we managed to gain a foothold in the northern part of Nimy. (…) Musketier Andreas Nissen was shot in the stomach and died a hero's death. It was not until about 2:30 in the afternoon that the enemy gave up the northern bank of the canal under the pressure of the well-placed artillery fire. Subsequent patrols found the railway bridge to the west of Nimy blown up and the swing bridge northwest of the village turned away to the south bank. In the heat of the moment, Musketier Niemeyer, from Röver's patrol of the 8th company, plunged into the water, swam across the canal and fetched a barge on which the patrol was able to cross despite heavy fire. While Röver with his men kept the enemy holding at the bridge under fire, Niemeyer succeeded in turning the bridge back so that the crossing was made possible for the following riflemen. Niemeyer suffered a hero's death immediately after performing this brave deed.’

While Niemeyer’s bravery is unquestioned and was clearly decisive for the German success on the day, none of the men above, not even Niemeyer’s company commander (who would have been the person to recommend him for the Iron Cross), mentions that he was decorated with an award of any kind. And this is not surprising, as the ‘Prusso-German’ Army generally knew no such thing as a posthumous award for bravery. There were a few exceptions, often based on an elaborate bending of rules and dates, but we can be sure that no such exception was made for Niemeyer. A similar example which underlines this fact, took place in Niemeyer’s regiment a few months later.

In Champagne on 6 July 1915, a mine had been blown under the French trenches opposite II./IR84. Immediately afterwards a sap was driven towards the resulting crater in an effort to incorporate and fortify the crater lip. Three men of 6th Company, fuelled by adrenalin and keen to distinguish themselves, jumped into the crater and started throwing hand grenades at the French infantry on the other side. The French replied in kind, wounding two of the Germans severely. One of them was Musketier Albert Bannier, who according to the commander of II. Bataillon had been ‘the best recruit of 1913’ and ‘a brave and fearless soldier’ who ‘had already distinguished himself many times in the past’. Oberleutnant Rabien, the commander of 6th Company, was present when Bannier succumbed to his wounds and later wrote that it was ‘painful that he [Bannier] did not yet have the Iron Cross.’ Banniers direct superior, Vizefeldwebel Albers, pleaded with Rabien ‘in order to give Bannier one last joy and recognition’ and ‘to arrange by telephone, if possible, for him to be awarded the Iron Cross before his demise.’ This however, as Rabien later wrote, was ‘unfortunately not possible any more’. After half an hour in full consciousness, Albert Bannier ‘joined the ranks of the Great Army.’

The Iron Cross wasn’t just a military award. Its value, importance and the esteem in which it was held in society since its first institution in 1813, can not be overestimated. In August 1914 and indeed for the first months of the war, winning an Iron Cross was a widely celebrated and publicised feat. It was the ultimate patriotic achievement, placing the winners into a continuous line with their forefathers, who had forged and united the German Fatherland in the shadow of this ‘sacred symbol’

‘For the third time, German men fight for possession of and in the sign of the Iron Cross, for the third time a Hohenzollern established the Iron Cross as a sign and honour of German bravery, for the third time the German Iron Cross finds a strong and heroic lineage. There can be no better sign of German heroism than this simple Iron Cross, no more beautiful a symbol of the brave trust in God with which our good soldiers go to face the enemy. Under the Iron Cross the German people fought for freedom and honour 100 years ago, 48 years ago they forged their unity under this very symbol, and now they are going into the field to fight the most difficult battle of all (...)’ - Kölner Lokal-Anzeiger, 12 September 1914.

If Oskar Niemeyer had indeed been the first German soldier to win the Iron Cross, there is no doubt that we could find a record of it somewhere.

BAGS FULL OF EVIDENCE

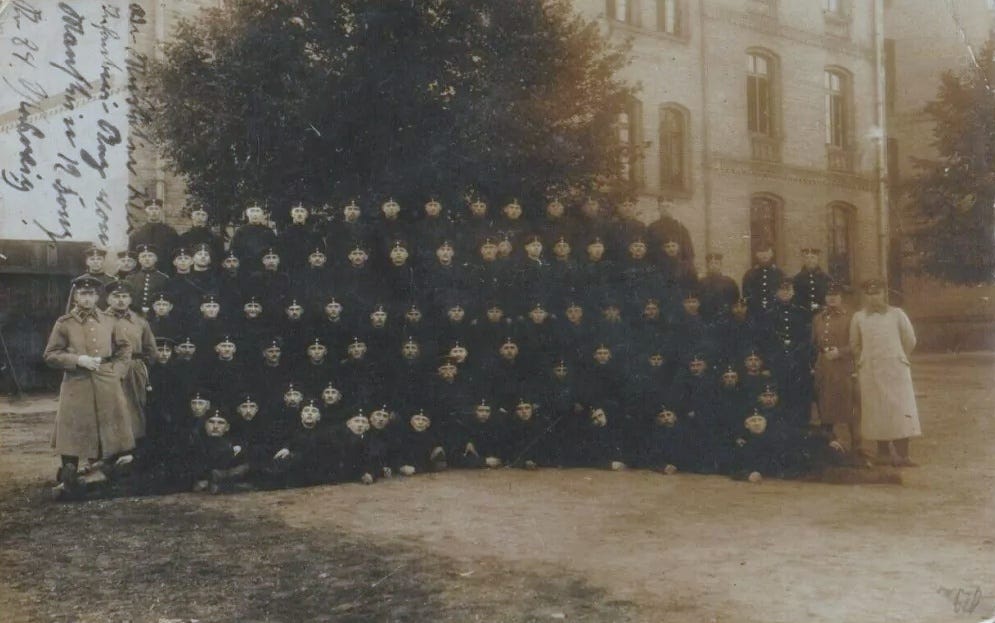

There are bags full of evidence which show that Niemeyer was never decorated with the Iron Cross, and that even if he had been, he would not have been the first soldier of the German Army to win it. In fact he would not even have been the first man within his own regiment! In 1922, the former commander of 6th company of IR84 remembered that on 20 August 1914, near Les Baraques in France, he and the other company commanders of II./IR84 (‘lying on our bellies in the chaussee trench’) wrote the first recommendations for all those who, in the previous 14 days, had distinguished themselves enough to be considered for an Iron Cross. On 23 September 1914, three days after IX Army Corps had delivered the first batch of Iron Crosses to the regiment, some men of II. Battalion received the ‘First Iron Crosses for the Battle of the Gette on 18 August’. On that day, the first enlisted man of 7th Company to receive the actual award in its paper wrapper, was Gefreiter Kruse, the company drummer.

“Apart from Hauptmann Mende, the brave Tambour Kruse of 7th company received this well-deserved award. When on 18 August we saw the first heads emerge from the Belgian positions in the action near Tirlemont, Kruse could no longer be held back. ‘Well, off we go!’, he shouted to those lying near him and drummed the signal for the assault. His drumbeat swept everyone with him, and in no time at all the enemy positions were overrun in their entire depth; the front platoon had had no casualties. At Esternay, in the midst of heavy enemy fire, Kruse, with the drum under his arm, advanced behind the firing line, controlling the actions of the individual riflemen. When his drum was shot to pieces, he took up a rifle, which he has not let out of his hand since.”

On that day Gefreiter Tambour Kruse was decorated for his actions on 18 August, 5 days before Niemeyer so bravely jumped into the water of the Condé Canal. That fact alone should be enough to destroy the ‘first Iron Cross in the German Army’ myth once and for all, but just for the sake of it, let's go a few steps further.

We now know that the first Iron Cross recommendations for soldiers of IR84 were written at least three days before Niemeyer’s tragic demise. We have established that the first Iron Crosses were only delivered to the regiment on 20 September 1914, and that the first men (who had earned them days before Niemeyer’s deed) were decorated with them three days after that. This rules out any spontaneous or irregular ‘in the field’ decoration of a dying soldier, which could have been entered into the records post mortem (which did indeed happen now and then). There were no Iron Crosses available when Niemeyer passed away. In fact Leutnant Franz Heyne, who in 1914 served in the regimental baggage train, noted in his diary that the first time he saw troops wearing Iron Crosses, was on 18 September 1914, when passing a column of Prussian cavalry near Château de Pinon. He hadn’t seen any in his own regiment.

On 13 August 1914, Hauptmann Hermann Meyer, then serving on the Great General Staff, was decorated for his actions during the attack on Liege on 7 August 1914. The press all over Germany hailed him as ‘first recipient of the Iron Cross’. Although a short biography was published by the Stuttgarter Tagblatt on the occasion of Geyer’s 60th birthday in 1942 (when he was General in command of IX. Army Corps of the Wehrmacht), relativised this by stating he had in fact been the first officer from Württemberg to receive the award. Prussian General Staff Officer Bodo von Harbou, who played an important role in the capture of the city of Liege (which capitulated on 16 August), was the first to be decorated with the Iron Cross by the Kaiser himself on 22 August 1914. Leutnant Freiherr Friedrich von Martels zu Dankern won his Iron Cross 2nd Class on 19 August 1914 and was declared the first man on the Eastern Front to win the award. From 25/26 August 1914, newspapers all across Germany began to proudly announce the first local winners of the Iron Cross, not bothering to even try to claim that one was the ‘first German soldier’ to so decorated.

Even though Iron Cross award numbers in the first months of the war were indeed low, German troops on all fronts had already won or had been recommended for an Iron Cross by the time of Niemeyer’s feat. Only a week after mobilisation and activation of the reserves, the German Army had about 3,8 Million men under arms. On 23 August 1914, when Niemeyer supposedly became the first man of the German Army to win the cross, hundreds of men were actually doing the same and survived long enough to be actually decorated with it.

To put this further into perspective, on the same day (23 August 1914) five British soldiers conducted acts of bravery which would win them the Victoria Cross, in an army in which rewarding individual bravery was traditionally uncommon and which at the time numbered only about 130,000 men. In fact, so many German soldiers won the Iron Cross in the second half of August 1914, that even high command, army staffs, the press and the public found it impossible to decide who actually won it first. Today we still do not know. It gets a bit easier when looking at the far more prestigious Iron Cross First Class, the first of which were awarded to frontline troops a few weeks later, but this is another story and one of many you will be able to read about in my forthcoming book [apologies for the shameless advertising].

Some sources:

Hülsemann, Geschichte des Infanterie-Regiments von Manstein (Schleswigsches) Nr. 84 (1914 - 1918), in Einzeldarstellungen von Frontkämpfern. Erinnerungsblätter der ehemaligen Mansteiner. 1929 Hamburg, Volume 1.

Various issues of : ‘Allzeit Voran! - Regiments-Zeitung der ehem. 84er’

Soldaten und Garnisonen in Pommern und im Bezirk des II. Armee-Korps. Krister R. G. E. v Albedyll. Léon Sauniers Buchhandlung, 1926

Outstanding article - myth slaying at its very best

Absolutely brilliant. I love your work. Proper, niche and nerdy military history.