'A DIRTY DUTY WELL PERFORMED' - GERMAN SNIPERS IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR

The first of four parts, taking unique look at Germany's ‘Zielfernrohrschützen’, the “scoped rifle marksmen” - who were they, and how did they operate? A look past myth and fantasy.

‘Besides I have been assigned a wonderful job. I am now a sniper and do a lot of observing work. Whenever I feel like it, I walk to the observing post where there is a so-called 'scissor' telescope, through which I can observe everything that is going on on the English side. When I spot an Englishman who is bold enough to raise his nose, it is my duty and obligation to shoot him. I do not need to do any sentry duty and am allowed to sleep at night and that while everyone else is on their feet. I feel like I am in heaven!‘

Ignaz Hautumm, Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment 236, 21 April 1916

ENTER THE SNIPER

A lot has been written about the dangerous world of sniping during the First World War. Most of it, however, focuses on the Allied side. Was the first school of sniping really established in Great Britain? Was Francis Pegahmagabow really the most effective sniper of the First World War? Are statements like this not only based on the fact that we know very little about what went on across the barbed wire? The few books which dare tackle the subject of German sniping, focus on the weapons and rifle scopes used, and fail abysmally when it comes to the subject of ‘the sniper’ himself. The author of this feature has not encountered any English language title worth its salt when it comes to the subject of the Zielfernrohrschützen and Scharfschützen of the Great War. The basis for most of the existing writing seems to be myth, hearsay and pure fantasy. Due to the near total destruction of Prussian First World War records in a bombing raid on Potsdam in April 1945, it is indeed difficult to find hard evidence of Germany’s snipers. And even where records survive, for example those of the Bavarian Army in the Kriegsarchiv in Munich, the sparse facts usually revolve around distribution and use of rifle scopes, scope mounts and other technicalities.

In this feature we take a closer look at the men themselves, the ‘Zielfernrohrschützen’, the “scoped rifle marksmen”, how they operated and how Germany deployed them.

Since I am the best shot in my company I was issued with a special rifle which mounts a telescopic sight! Both rifle and optics are of similar quality to that on my old Simson, but here I hunt a different prey. Each morning I choose my deerstand, which has to offer a good view of the English positions and wait. When a cap appears over the parapet or I see movement through a loophole I pull the trigger. Sadly I rarely have the chance to confirm my success, but it is an interesting and exciting work!

Gefr. Hermann Kieser, Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment 248, 23 January 1915

THE STRAY BULLET

By the end of 1914 the fluidity of battle on the Western Front had come to an end when the lines solidified. Both sides dug in, seeking shelter from the destructive power of modern weaponry in deep systems of trenches, fortified strongpoints and barbed wire entanglements which stretched from the Belgian North Sea Coast, across north-eastern France to the border of Switzerland. On the enormous length of the Eastern Front armies continued to manoeuvre in sweeping movements, often achieving decisive breakthroughs which resulted in enormous advances. On the Eastern front, trench warfare existed, but it would never be the defining motif of the fighting there. Yet on both fronts, soldiers facing the Germans soon encountered the same, new phenomenon of which only few took any account of at first.

This phenomenon becomes very apparent when looking at the personal accounts of British soldiers, published in the newspapers during this early period of the war. “My chum was struck at the back of the ear by a stray bullet and killed on the spot.”, “(...) the doctor then told us that his case was hopeless, he had been hit in the head by the stray bullet.”, “he was walking up and down the support trench he was unfortunately struck by a stray bullet which hit him at the back of his head.”, “(...) the Lance-Corporal, a Buxton man, was shot through the heart by a stray bullet, whilst engaged with a working party some distance behind the trench.”. Random, but for some reason pretty accurate, “stray bullets” were responsible for a great number of British casualties. Yet the more static the war on the Western Front became, the clearer it was that these incidents, even in quiet parts of the line, could just not be explained by some stray bullets finding a particularly unlucky target. Indeed the French and the Belgians in the West, as well as Russian troops on the Eastern Front experienced the same phenomenon, but it was less well, or in the case of Russia, not at all documented. By Spring 1915 most soldiers on the Allied side of the barbed wire knew that there were highly effective German marksmen armed with scoped rifles on the hunt for prey.

Major Hesketh-Prichard, who made a significant contribution to the development of sniping practice in the British Army, described this in his book Sniping in France: ‘At this time the skill of the German sniper had become a by-word, and in the early days of trench warfare brave German riflemen used to lie out between the lines, sending their bullets through the head of any officer or man who dared to look over our parapet (...) Only those who have been in a trench opposite Hun snipers that had the mastery, know what a hell life can be made under these conditions. I don't think the Germans are better snipers than our men, except that they are more patient and better organised and better equipped.’

CITIZEN MARKSMEN

Early in the war British newspapers were abundant with stories propagating the prowess of arms of the soldiers of the BEF, who not only fired a lot faster than their German adversaries, but were also a lot more accurate. In 1914, it was only the sheer weight of numbers which had caused the professional British soldiers to withdraw in the face of the German advance. German conscripts, often badly led, advanced in solid blocks of men, making excellent targets for highly accurate, rapid British rifle fire. They were generally bad shots, often firing high and regularly missing their targets, while in addition they were so blinkered, that they could not distinguish the sound of rifle fire from that of machine guns. Even though one would think that comical statements of the kind, which were produced and spread by British propaganda at the time, would have been forgotten in the years following the Great War, they have instead become lore, accepted truths that continue to resurface in literature and in the media. This is not the place to discuss the ins and outs of German leadership, doctrine and army training at the brink of the First World War, yet it is important for this article to take a closer look at the importance that the German Army, in all its contingents, put on the rifle and marksmanship training of its soldiers.

There is a lot of things to learn here, but I like the shooting most. Today we have been shooting again, amidst a scurry of snow. I could hardly see the targets, but I made a good job of it. At the moment half of our company has an extra hour of marksmanship training at noon. Last week there was a shooting competition where I scored 41 rings. Today I scored 39 and we only need to hit 30 (…)

Peter Schmelzer, I. Ersatz-Batl., Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 473, 14 January 1916

ARMY TRAINING - THE IMPORTANCE OF MARKSMANSHIP

Since 1871, every able-bodied German male between the age of 17 and 45 was liable for compulsory military service, which broadly followed a progression through various tiers of service based on age. At the age of 17 or 18 young men were formally registered with the Landsturm, which meant that from that time they could, if needed, be called up to defend home and hearth in times of war. Yet proper military training started when they had reached the age of 20 and entered the Aktiver Dienst [active service] period, which meant service for a two year stint (three in mounted units). Upon finishing their active service time, they were discharged to civilian life and moved on to the Reserve for 4-5 years were they would be regularly called up for military training excercises to keep them in shape. Next, the older soldiers would be transferred into the Landwehr reserve pool for 7 years, where they would be called up twice a year to refresh their military skills and finally, for another 7 years, into the Landsturm reserve in which no training exercises were conducted. During the whole time of those 21 years a reservist could be called up to take up arms for his country. A great emphasis during training in active and reserve service time was placed on individual marksmanship. A recruit soldier would not only be trained in combat shooting as part of a platoon or company, but would also undergo intense individual rifle drill and dry and live-firing exercises on static and moving targets.

Service here is more or less the identical to that in the barracks but it seems that it is to start all over again! When our Hauptmann welcomed us he said that we had learned nothing so far! Yesterday we had to do manual labour for 3 1/2 hours and started building a shooting range on which we will train in the coming weeks.

Karl Lindner, Rekruten-Depot 7, I. Bayerisches Armeekorps. 22 January 1915

Company commanders took great care and effort to turn their soldiers into the best shots of their regiment, as they were being held personally responsible for the marksmanship results of their men. In barracks soldiers were given constant access to their rifles which were stored unlocked in racks, close to the soldiers quarters. During off-duty time it was taken for granted that the men practised drill and cared for their rifles. To control marksmanship performance, a company commander could always access his soldiers firing results, as each man was required to keep a Schiessbuch, or shooting book, into which he had to enter the results of a prescribed firing table, which he had to complete with at least minimum standards and which he had to repeat until he managed to do so. The combined results of all men who were then entered into the Kompanie-Schiessbuch (company shooting book) where they were closely monitored not only by the battalion, but also by the regimental commander himself. From 1895 onwards, all regiments of the German Army´s contingents held shooting competitions on a Corps basis and had to participate in the so-called Kaiserschiessen, or Königsschiessen as it was known in the armies of Saxony, Württemberg and Bavaria. These were shooting contests in which one regiment’s company with the best marksmanship results in its respective Army Corps was rewarded with the highly regarded Kaiser (or Königsabzeichen). The gilded metal wreath surrounding two crossed rifles (for the infantry) would then be worn by all men of that company for one year up to the date of the next annual shooting contest. Excellent individual marksmanship was further rewarded by the award of a Schutzenschnur, the marksman lanyard, which was awarded in 10 classes and worn on the uniform in the early stages of the war.

RIFLE ASSOCIATIONS AND HUNTSMEN

In Britain, hunting was an exclusive and expensive sport and very much the preserve of the upper classes. In Germany, with its 32 million acres of forest (in 1913), forestry and hunting were an industry of major importance. Not only were there enormous numbers of state employed foresters and hunters required to sustain this industry, but private licensed hunting was common in all levels of society. As a result of the revolution of 1848, the hunting regimes of the nobility had been abolished and every citizen was allowed to hunt on his own grounds or with permission of the ground owners. In more remote areas of Germany, in the Eifel, the Hunsrück, the Harz mountains or the Alpine regions (to name just a few). it was still common that young men would learn the basics of fieldcraft, stalking and shooting, before being taken into the adult community. In the villages, towns and cities all over Germany Schützenvereine, Schützengilden and Schützenbruderschaften, rifleman associations, guilds and brotherhoods, drew thousand upon thousands of members.

A remnant of the medieval age where settlements had formed crossbow-, and later musket-armed militias to defend themselves from outside intruders and rampaging men-at-arms. These associations had seen a renovation and peak in popularity at the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The oldest were in continuous existence since the 12th century and although largely ceremonial in modern times, members still regularly honed their shooting skills on the range and held competitions against other associations. In addition, the rifle associations took an active role in training the reserves. On 19 May 1915, the ‘Darmstädter Tagblatt’ reported upon the important role of the local rifle association: “On Sunday 100 future conscripts assembled on the seven ranges of the rifle association where they received special marksmanship training for more than five hours. A total of 15000 rounds were fired, the cost of which was paid for by the city of Darmstadt. All men were thoroughly motivated by the knowledge that there is no skill more important in the field than that of shooting. The training program, which is now being copied by many other cities, was a great success and will in the future take place on every Sunday. At the instigation of Commerce Councilor Hickler another 115 scoped rifles have been made available by the war ministry and will be sent to Hessian troops in the field very soon.”

When the reserves were called up in August 1914 and the Reserve and Landwehr regiments were activated, it took the German Army only 12 days to expand from about 840,000 to three and a half million soldiers. In addition to the marksmanship training all of these men would have had during their army training, a large number of those called-up or already in active service would have had additional marksmanship skills honed in shooting guilds or on the hunt. It would be men like this who, equipped with scoped precision rifles would wreak havoc amongst the foe across the barbed wire.

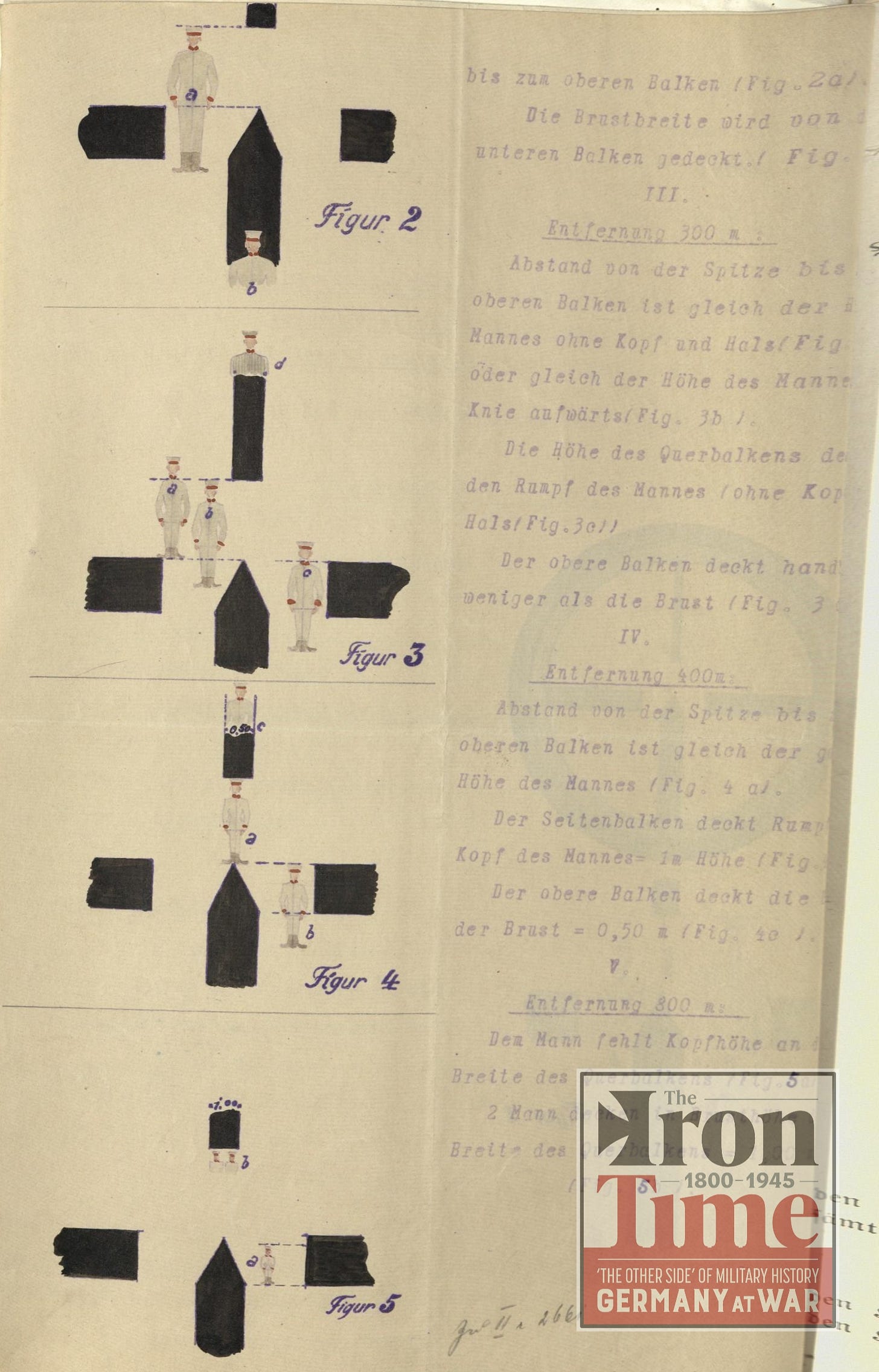

ZIELFERNROHR-GEWEHRE

Within the first days of the war the Germans quickly realised that to complement the mass destructive power of the machine gun and that field artillery, a more discriminating weapon would be required. Almost as soon as the first shots were fired in anger the first scoped hunting rifles were acquired to fill that role. These were weapons made for the civilian market mounting a variety of commercial telescopic sights made by Zeiss, Goerz and Gérard. These civilian rifles were chambered to fire the Patrone 88, rather than the new, powerful Mauser S-Patrone which had become the standard cartridge of the German Army in 1904/05. Even though these weapons were more delicate than a combat rifle and as such not ideal for trench usage, their apparent value in combat soon became apparent and efforts were taken to make them more available for army use. The old Viktor Amadeus, Duke of Ratibor, then a member of the Prussian cabinet, personally funded a program with the aim to collect 20,000 scoped rifles for frontline use and it is estimated that about 5000-8000 of them were gathered before the end of December 1914 when the program slowly fizzed out. Yet it was clear to the Army that these weapons could only form a stop-gap solution. At about the same time the Prussian War Ministry ordered the first 15,000 scoped Gewehr 98 combat rifles, known as the Scharfschützen-, or Zielfernrohr-Gewehr 98. The first batches of these rifles went to the Bavarian Army in the winter of 1914. The G98, the German Army's standard rifle during the First World War, though long barreled and a bit cumbersome, was powerful and accurate against man-sized targets up to a range of 600 metres, and still potentially lethal in ranges of about 2000 meters.The scoped versions of the G98 were a specifically selected and finished and as such, accurate examples of the standard rifle. The bolt handle was bent down and a recess to hold it cut into the stock. Other rifles had the underside of the bolt handle ground away to allow the stem to pass back under the mounted optical sight. German Army never had a standard telescopic sight although it was initially specified that 4x sights by Goerz and Zeiss were to be used. As those two companies could never satisfy demands virtually any other available rifle scope was pressed into service, makers included Ernst Busch in Rathenow, Voigtländer in Braunschweig, C.P. Goerz in Berlin, M. Hensoldt in Wetzlar and Carl Zeiss in Jena. Whereas most sights had 4x magnification, others ranged from 2 ¾x to 6x. Each rifle was zeroed in and paired with one specific rifle and both were numbered as such.

For further information on the weapons themselves and on the telescopic sights used I recommend looking into the works of Dieter Storz.

ZIELFERNROHRSCHÜTZEN

“Rifles with telescopic sights belong into the trenches and are only to be used for precision shooting. The scoped rifle can only be successfully used by the hands of a trained marksman who not only has a personal interest in precision shooting, but also brings with him the cold-bloodedness necessary to place a calm shot even when subjected to enemy fire. As such the men operating the scoped rifles have to be chosen very carefully. It is safe to say that there will be several in each company who are used to this kind of calm, precision shooting from the hunt, and who take personal pleasure and satisfaction from it.”

- Generalkommando, XIII. Armeekorps, IIc, June 1915

It is quite clear that differences existed in the way that snipers within the federal contingents and even within individual divisions of the German Army were employed, yet all of them, except for the Bavarian Army seemed to have modelled their sniper force after the Prussian model. Due to the limited scope of this article and because it generally seems that sniping played a much lesser role in the East, I have focused solely on the Western Front.

There is a lot of contradicting information on the distribution and number of scoped rifles within German regiments, which is mainly due to the severe lack of official records from the Prussian side. So far historians have thus focused on the distribution within the Bavarian army and, to a lesser extent, the army of Württemberg. It is safe to say, that distribution within these state contingents differed. Initially scoped rifles seem to have been issued on the scale of one per line infantry or Jäger company. After this the distribution among regiments becomes unclear. In some Bavarian units the number had risen to three per company in August 1916, while a report of the 26. Infanterie-Division (Württemberg) from April 1915 states that it was requested to have six scopes and an extra two in reserve for each of its regiment’s companies. A month later the 26., 27. and 28. Division each reported 18 scoped rifles available, while some Landwehr and other second rate units were still waiting for their allotment. By early 1917, each company in an infantry regiment would have had at least three rifles with telescopic sights at its disposal. Initially scoped rifles had to be returned to the armoury after use, where one armourer, usually an experienced NCO, was in charge of their care. However, this practice seems to have been abandoned within the first months of the war. In July 1916 the Prussian War Ministry ordered all remaining civilian hunting rifles still in service to be returned immediately, as they were badly needed in Germany.

How German snipers operated is still very much unexplored, and most of the information found in literature today is based on Allied wartime sources and simple speculation. A fascinating insight into the world of mid-war German sniping can be gained from a so-far unpublished report compiled by the 87. Infanterie-Brigade in the summer of 1917 which survives in a private collection in Germany:

“87. Inf. Brig.

Abt. I, Nr. 6781Zu Abt. I, Mun./Nr.7631/v. 15. 6. 1917

To the Generalkommando XVII. A.K.

Experiences from the work of the telescope rifle marksmen

The Brigade currently has 110 scoped rifles of various manufacturers available of which those equipped with telescopes made by the companies of Dr. Walter Gerard, Charlottenburg and by Voigtländer Braunschweig have proven themselves best. Each company has a complement of 10-15 trained scoped rifle marksmen. On operation it has become clear that the men work best when divided into Abschusskommandos [lit. ‘kill commands’] consisting of two marksmen and two observers. The observers are equipped with Gewehr 98, flare pistol and DF 03 6x binoculars. The use of the pattern 08 binoculars has to be refrained from, due to their limited field of vision and low magnification. In addition to the standard load-out the ZF-Schützen (scoped rifle marksmen) carry an additional 15 K-cartridges to use for long distance shooting and against hard targets. Members of the Abschusskommandos are exempt from labour duties. The Abschusskommandos, in a strength of 2 to 4 men, operate freely within the regimental sectors, work closely with the troops in the trenches and are subordinated to the KTK (Kampftruppenkommandeur). Wherever possible the ZF-Schützen cover one another during operations. Best success is still achieved at dawn and dusk, with illumination by the moon also at night. Today scoped rifles remain in the trenches. The responsibility of care and maintenance for the weapons lies with the individual operator.

The main combat zone of the ZF-Schützen is the trench, nevertheless good results have been achieved within the forefield and in shell crater positions. Typical engagement distances range between 100 and 400 metres. Although hits have been scored on distances of over 800 metres, it is often impossible to observe and confirm the actual effect of such long range shots.

For the Abschusskommandos operating in these positions good camouflage is of major importance. In that regard some of the men show a great eagerness making use of specifically tailored tent squares, face wrappings and individually dyed and painted pieces of uniform. A kill can only be classed as confirmed when it has been performed under observation of a witness. All kills, confirmed and unconfirmed, are entered in the Abschussbuch register with information on: time, location, distance, ammunition used, target identification and effect. A notably successful and distinguished marksmen is Gefreiter Anton Gaskowski of 5th company, IR 176. Since the start of the Battle of the Somme until today he has registered 79 confirmed kills. Some regiments pay head bounties for confirmed kills from their regimental coffers, which has notably increased the number of confirmed kills (IR141 pays 10 Marks for every enlisted and 20 Marks for every officer shot). Yet this is not well received by all of the men as many consider this to be dishonourable and beneath the dignity of the German soldier. A first selection and basic training of the ZF-Schützen is nowadays already conducted with the replacement battalions. There men with hunting or similiar shooting experience are chosen before they receive further training by experienced marksmen in the field. For the training of promising candidates within the regiment the Zielfernrohr-Kurse (telescopic sight courses) have proven themselves greatly since their initiation in April 1915. One main task is the annihilation of the enemy’s scoped rifle marksmen, whose number and quality on the English side have strongly increased during the previous months. Even though the English optical sights are far inferior to ours, some innovations of the enemy, like industrially manufactured target dummies made of wood or Papier-mâché, are noteworthy. The far inferior quality of the enemy’s optical devices can also be judged by the fact that he usually ceases precision fire after dusk. The experiences since the start of the war have shown that amongst our foes the English are the best precision shooters and come before the French, who make little use of scoped rifles. The Russians don’t seem to employ scoped rifles at all.” [With thanks to the Walther Sterz Collection]

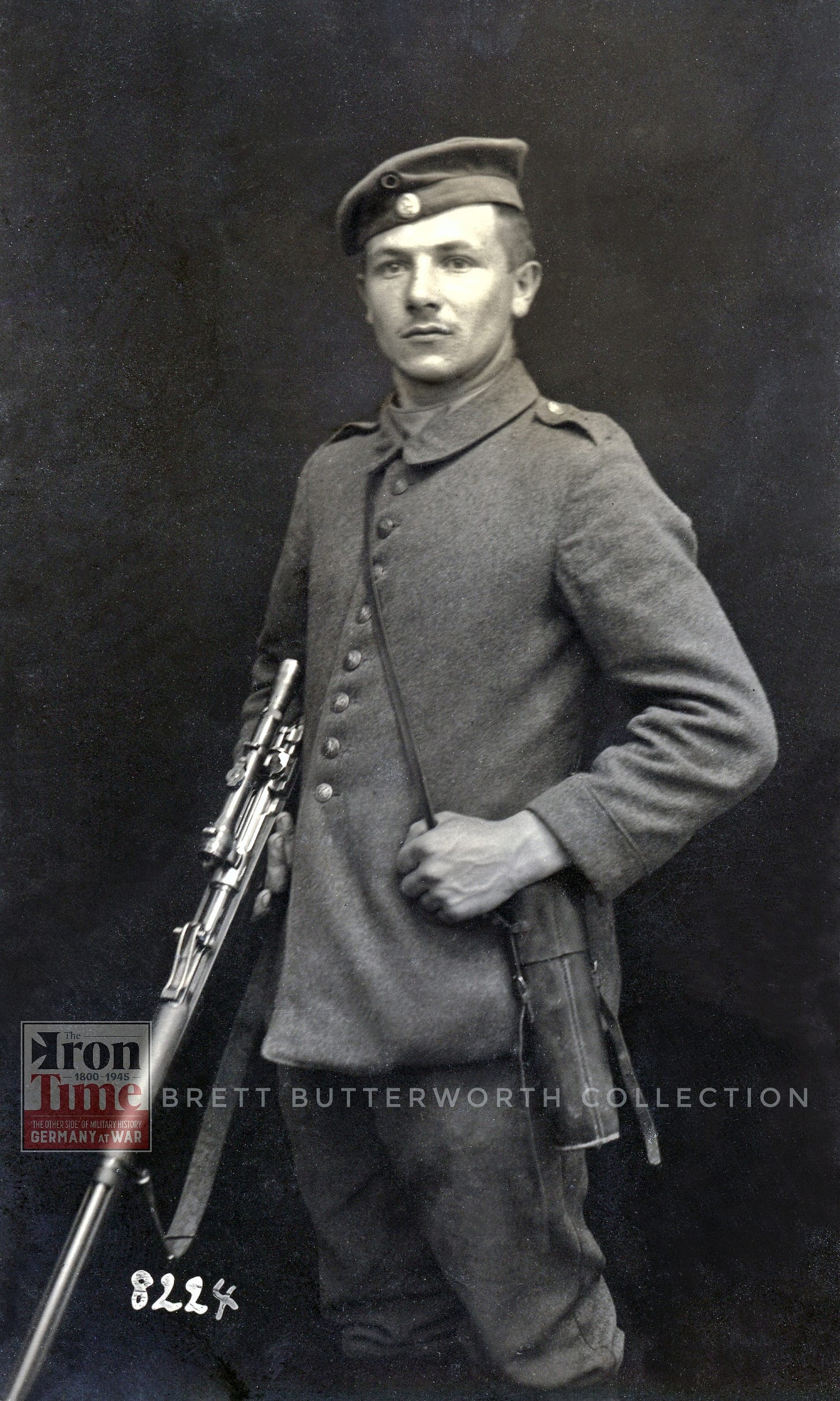

Scharfschütze Vitus Heiss of the Royal Bavarian 16. Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment also known as the ‘List Regiment’. Heiss was killed by a headshot on 12th May 1917 near Roeux in France.

A DIRTY DUTY

A quick look through the internet and a flick through available literature about the First World War will be enough to come up with the names of the most successful snipers, like Francis Pegahmagabow, Billy Singh and Henry Norwest. Not a single German name makes an appearance [ignore the often mentioned fantasy sniper ‘Georg Schmidt’]. Looking at the fact that it was the German Army which first deployed telescope rifle armed marksmen on the battlefield and which developed the tactics and operational principles, which later formed the basis for the creation and development of other nations sniper forces, this seems a bit odd. One reason is surely found in disinterest, another in difficulties for international researchers to access and (more importantly) to read and understand the available German sources. The third reason is the aforementioned destruction of records in the Second World War. A fourth reason however, is found in the near-total lack of mentions of German sniping in published German sources. In the hundreds of super-detailed regimental histories published after the war, in which all manners of prowess at arms are celebrated to great extent, one only finds a handful of mentions of the work of German snipers. So why is that the case? The answer might be found in a letter written by young Leutnant Dietz von Saucken (GGR 3) to his friend Leutnant Joachim von Kortzfleisch (IR43) on 22 November 1916 in which he reports that: “During the period at Beuvraignes we did our best to give those opposite a good spanking. Some men of my company have become very proficient working with telescope rifle sights and merrily kept the Monsieurs on their feet. One man in particular has done in over 20 of them during only 5 days. A dirty duty, even if well performed, doesn't deserve an award from the Fatherland, so I presented him with a simple silver pocket watch instead (...).” A silver pocket watch as reward for a dirty duty well performed, seems similar to mentions of per-head bounty in cash, which was seemingly paid by some German regiments. The work of the sniper, though important and valued, might not have been considered honourable enough to deserve high awards and mentions in the press and post-war regimental literature.

This is outstanding work Very glad to have found this Substack and have subscribed.

Im new to your blog and this is the first article I’ve read. A very good read it was too.

It’s a subject I’ve often wondered about.

As you mention, the volume of sniping early in the war in British accounts that refer to stray bullets has always made me wonder what the writer thought was being shot at, if not by a sniper.