BROTHERS OF THE BLADE: TWO LIVES AGAINST NAPOLEON (2)

INSTALMENT NO. 2 : LONDON, JULY TO SEPTEMBER 1810

Editor’s note: Here Moritz von Hirschfeld introduces us to the diary of his brother Eugen, and also to his own experiences in London and on the sea voyage to Spain, where he would reunite with his beloved brother.

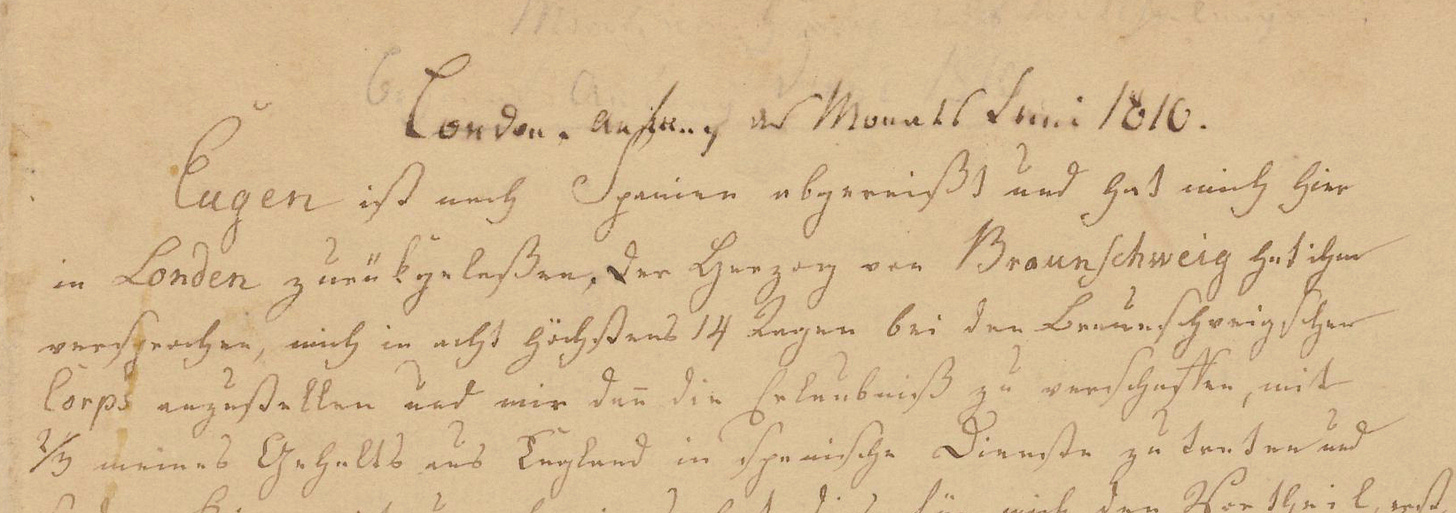

London at the beginning of the month of June 1810

Eugen has departed for Spain and left me behind here in London. The Duke of Brunswick has promised that he would send me to the Brunswick Corps in 8 days, at most 14 days, and then to get me permission to enter Spanish service with 2/3 of my salary paid from England and thus to take part in the war. This has two advantages for me, firstly of doubling my salary and secondly, if I should become a cripple, that of being eligible for an English pension. Surely Eugen's intentions and care are the best. Saying goodbye to Eugen was very difficult for me, and I would have wished he had taken me with him right away; I feel very abandoned and lonely in big, prosperous London, have few acquaintances, and association with the English is almost impossible to achieve because of their cold, repulsive character. I gave up my quarters immediately after Eugen's departure because they were too expensive for me, and moved into a very small room on the ground floor in a very narrow alley; the whole ameublement consisted of a very simple bed , two chairs and a table. Everything seemed to be from the time of Cromwell. The house was a kind of boarding house; the woman who was in charge of this household was a widow. Great cleanliness, good naturedness and order were her chief virtues; as for her faults, her only one she shared with me -- poverty. My money was almost at an end, and from the Duke, in spite of all my inquiries about my employment, I heard nothing at all; if he didn’t keep his word, I don't know how it would have gone. I had nothing to do either, and the time was getting very long for me. Everything there was terribly expensive; I cleaned my things myself and had a small piece of bread for breakfast; I also did the laundry myself. I didn't think it would be like that when I left for England full of golden plans. The first two shirts turned my blood sour , especially the stupid thick folds in the collars. To make sure that my landlady didn’t notice anything, I had a bucket of water put in my room each evening to wash my feet, and when everyone was asleep, the laundry started, which was then hung over chairs and tables to be dry and ironed on the next morning with an empty glass wine bottle, especially the collar and other visible parts.

The Duke told me he could not employ me. Eugen and I had relied entirely on the Duke's word, and I was therefore only weakly provided with money; I felt really terrible; without money , acquaintances and friends, all alone in London, that was a difficult situation! One of my few acquaintances, who travelled from Germany to England with us at the same time and whom Eugen knew before, was brought to King’s Bench because of debts; His name was Löffler and he was from Havelberg, a very smart young man of 28 years. When we arrived in England, he was employed as an officer in a dragoon regiment of the English-German Legion, with the promise that his relatives would cover the very expensive equipage. He owed Eugen not inconsiderable sums; the funds for the equipage never arrived; he lived like a rich young man and finally ended up in debtor's prison. I often visited him in King's Bench, and even though it’s a debtor's prison it is most tolerable. It consists of a very large four-storey building with a courtyard, which forms half a square. The whole thing is enclosed by a very high wall, on the edge of which are iron barriers. The prisoners can move around in this space as they wish, and many continue their previous trades and, if they want a somewhat larger place than is their due - which is a small room without furniture and bed for four people - the same has to be rented from the director. One therefore found innkeepers, coffee rooms, billiard tables and all kinds of craftsmen; I used to have lunch there because it was very good and cheap. Every prisoner has to take care of the necessities of life himself; those who can not do this are taken to another prison, where the prisoners are to be fed by the state, which due to corruption however, is done in a horribly poor manner.

For me the thing had the good effect that I developed a tremendous loathing of going into debt. Many of my acquaintances from that time have perished there abroad in a most miserable way through their careless running up of debt, although the possibility was there for them, albeit with some sacrifice, to get through life without it. I was now at the point, since all other avenues of advancement and employment were closed to me, to join the English 60th Regiment as an officer. This regiment consists mostly of foreigners, most of them Germans, and has 6 battalions two of which are permanently stationed in the West Indies; every year one of the battalions there is relieved by a battalion of the same regiment in England, and then, apart from the staff, the few non-commissioned officers and soldiers who do return usually do so in a very sad and thoroughly bad physical condition; all this due to the unhealthy climate. It is true, this regiment offers a very good chance of advancement, and as a rule five years is counted as the longest time it will take the most junior officer to advance to Captain; yet only few get to experience that promotion, and many are crippled for life. However, I was determined to risk it; in the end it was better than starvation.

In the meantime a German merchant made me the offer to take me to Hamburg free of charge; but should I have gone back to my father, who had enough to do with my siblings, and eat the bread from under their noses? - I didn’t want that; I had started this and didn’t want to turn back halfway, come what may. I should have acted earlier and looked for some employment as soon as we arrived in England, so as not to be a burden to poor Eugen. However, since we came to England with the intention of going to Spain and could not have foreseen that this matter would be delayed for so long, I always expected something would happen and the time just passed by without any result. If there had only been someone to give me a nod or, even better, had told me how things stood, I would have acted in a different way - then it would still have been possible to find employment in the English-German Legion, where in those early stages it was possible to purchase the equipage even with limited means, which later became an impossibility.

My previous upbringing and the perpetual guardianship in which I always lived, as well as the general opinion of my siblings and relatives, that I was in no way capable of a strong and quick decision, which shone through on so many occasions, had made me self-conscious from an early age and my sense of independence and self-confidence was very depressed. It depressed me even more in the presence of my relatives, so that I often felt bad about myself and was aware that especially in their presence I usually had to appear in a very unfavourable light. This feeling disappeared completely when I was left to myself among complete strangers; I then acted, as Eugen often told me, resolutely and correctly, and I have to admit that I was surprised at first by my good and rapid success. And even later, when I acted in difficult and desperate situations in my life, I was accused of great rigidity, obstinacy and perseverance; this perseverance has almost always led me to good results. With regard to my appointment to the 60th Regiment, I had just begun to take the necessary steps when I found an opportunity to communicate my decision to Colonel Dörnberg and to ask for his employment; he immediately wanted to help me out of my distress with an advance of money; but since I had no prospect of repaying him, I refused. However, he promised me that I would be employed again by the Duke, which also turned out to be in my favour.

The Duke summoned me the next day and announced his willingness to help me and in order to test my usefulness and to be able to recommend me with conviction , gave me a little test of my knowledge. The first questions he put to me in history were about the Crusades. I had happened to borrow, entirely out of boredom, an outline of the Crusades from a Captain Hoffmann, and having nothing better to do in London, I went through it very carefully, noting down the dates and names of the most prominent persons and places. The answers rolled out like the Lord’s Prayer, I always answered more and more extensively than the Duke had expected, including the place and time, so that I could see that the gracious gentleman had not expected it. I obviously knew more than he remembered from his school years. It was only later that I found out from Major von Oppen, who laughed a lot about the Duke's exams, that the Duke had also studied an English work on the Crusades, and had therefore probably made it the choice for the exams. The examination then passed to fortification and artillery; I had been very diligent in both subjects at the Junker school, since both subjects, artillery in particular, gave me a great deal of pleasure. I had benefited from this, so my exam went excellently here too, to the more and more visible astonishment of my senior examiner, who now went on to the little war and field service. Eugen had worked through this branch of service very thoroughly with me, since he considered it absolutely necessary for our forthcoming career, and used Scharnhorst's book as a basis, which I also owned, and I can well say that this instruction helped me in later years in the field and always been of great use. It was in a sense the guide I took as the basis of my military decisions. The Duke seemed to have drawn his wisdom from the same source, and I could clearly see his astonishment at my knowledge and my erudition. He dismissed me with very kind and flattering expressions and, since he had convinced himself of my usefulness, promised me an advance of 30 Pounds Sterling, which was paid to me the next day. Later he spoke very favourably to others about my abilities and knowledge in all subjects and stated that he had not expected this thorough and solid knowledge from me.

I now made an effort, and all my striving was aimed at getting free passage with provisions to Spain, like the English officers and officials, and although Colonel von Dörnberg and several other gentlemen were very helpful to me, the matter did not go well until chance again became my greatest helper. At the time of my great distress, when things were going really badly for me, even before the Duke declared himself in my favour, a German merchant, who had offered me free travel to Hamburg, had promised to transport a letter from Eugen from Cadiz to Brandenburg. So, since the man lived near the Tower and I did not want to miss him , I went out very early to meet him. There was still a dense fog , such as it usually lasts until 10 o'clock in the morning and even later , especially in London, and the streets were still fairly empty. I was then living in the James Park area, and therefore had to walk through Piccadilly, Haymarket, Charing Cross and the City, The Strand, to get to the merchant. I therefore walked briskly along the sidewalk and had arrived near St. Paul's Church when I saw a wallet lying in front of me on the sidewalk; I picked it up and examined it. It was made of red leather and tied together with a green woollen band. I opened it, to find an address or a card of the owner, but found that it was filled with bank notes. On the top a whole bundle of 100-pound notes and others were of even higher value. It was still very early and there were very few people on the street, so I went completely unnoticed; I tied the wallet close again and looked around for someone who might have lost it. The only one I noticed was a small, well-dressed man in an overcoat walking at some distance in front of me; So I followed him to ask if he had lost his wallet. I have to say here that the doubt as to whether I should keep the money or look for the owner in my oppressively poor and absolutely penniless situation, without prospect for the future, rose up in me, and it really cost me an effort to overcome it and to run after the man, who was in front of me, who I took for the rightful owner. But the Prussian officer and the nobleman in me soon helped to overcome these not very noble doubts and I did what was right. The man didn't want to take notice of me at first; but when he heard about the wallet, he turned pale except for his blue nose and reached for his breast pocket where he immediately noticed the loss. After he had now given the necessary description of the contents of 3000 and a few 100 pounds, I handed him his property and now believed that the man would throw his arms around my neck and dissolve in gratitude. Instead he grabbed it very greedily, carefully counted the contents, took out two £10 notes and held them out to me with a very cold, contemptuous expression, much like offering a tip to a servant. As poor as I was at that moment, and as much as I could have used those 20 pounds, all my feelings about the nature of such treatment revolted. I wanted to punch the man in the face, so I turned around without answering him and went on my way. After a while I looked around for him; he was still standing quite stiffly on the same spot, the wallet in one hand, the two notes in the other, and he was watching me. It probably hadn't occurred to him that someone didn't want to accept money.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to THE IRON TIME to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.