Every now and then I come across documents, whose content is so unusual that, although there is no big story to be told, I simply have to share them. This report, written by Oberleutnant König of the intel-section (Ic) of Feldluftgaukommando Westfrankreich [Air District Command Western France], is such a case. Today it is found in file RL 7-3/599 in the Federal Archives in Freiburg, in an attachment folder for a war diary which doesn’t exists anymore. It tells the story of a rather peculiar, and unsuccessful, desertion attempt of two German Fallschirmjäger.

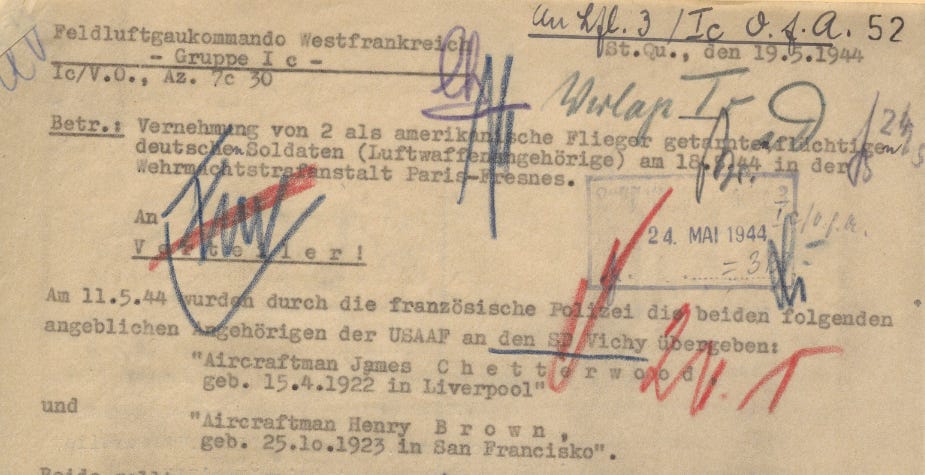

Interrogation of 2 fugitive German soldiers (Luftwaffenangehörige) disguised as American airmen on 18.05.1944 in the Paris-Fresnes penitentiary.

On 11.05.44, the French police handed over the following two alleged members of the USAAF to the SD-Vichy:

"Aircraftman James Chetterwood, born 15.4.1922 in Liverpool".

"Aircraftman Henry Brown, born 25.10.1923 in San Francisco".

Both were to be sent from Clermont-Ferrand to the Auswertestelle West Oberursel1, as they had declared the following:

They were members of the American Air Force and had been shot down during an attack on Frankfurt am Main on 18.4.44 near that city. After the crash, they had immediately removed their flying suits, under which they were wearing German airmen's uniforms: Tunics, trousers, cap and belt. They claimed to have destroyed their papers immediately after being shot down and then turned to France via Mainz and Saarbrücken in order to escape to Spain. Near Chaumont (Haute Marne), they exchanged their German uniforms for civilian clothing. Shortly before their arrest by the French police, they entered a French farmhouse whose occupants were absent and appropriated food and 2 pairs of civilian trousers. In their possession were pistols with ammunition, including an English escape handkerchief, such as those contained in the RAF or USAAF escape bags.

The following facts made the statements of the two aforementioned, appear suspect from the outset:

1.) Their rank designation "Aircraftman" is not used either by RAF or USAF aircrew.

2) There has been no known case of USAF personnel bailing out of combat aircraft with German uniforms under their flying suits.

3) The identification numbers given by the prisoners (1417 and 1512) were four digits in contrast to the USAAF numbers which are at least six digits long. Neither of them had a dog tag.

The fourth suspicious factor that immediately emerged during the interrogation was the inadequate command of the English language on the part of the two prisoners. The interrogation took place individually.

The alleged Henry Brown, who was interrogated first and who, after a short interrogation in English, was told in German that he could not be a downed US airman for the reasons mentioned above, but that he must be German in language, appearance and demeanour, nevertheless stuck to his original statements and foolishly claimed that he did not understand German. Asked about his duties within the crew, he described himself as a 'telegraph operator' (!) (RAF members call themselves 'wireless operators' and USAAF members 'radio men'). His request to be allowed to speak to his comrade, in order to apparently get instructions for his further behaviour, was refused by the undersigned and his interrogation was initially discontinued.

The second interviewee ("Chetterwoood"), after giving his name, rank and identification number, attempted to evade the exposure of his insufficient knowledge of the English language by refusing to give further information. After pointing out the above-mentioned grounds for suspicion and evidence against his USAAF affiliation and urging him to tell the truth, the alleged James Chetterwood confessed as follows:

His real name and personal details:

Gefreiter Arthur Baltrusch, born 16.6.22, last unit: 13./Fallschirmjäger-Ausbildungs-Regiment Commercy.

The real name of the alleged Brown was: Gefreiter Schille.

B. claims to have been wounded in the East and to have volunteered for the Fallschirmjäger. As a result of his wound (missing a finger and a bullet wound in the right upper arm) he had not been able to fully meet the requirements of the service, had felt unjustly treated and had absconded under the mask of a shot-down airman, expecting that even if he were discovered by the French police, they would not put any obstacle in the way of his being forwarded to the Spanish border.

During the second interrogation of Gefreiter Schille, he gave his personal details as follows:

Gefreiter Manfred Schille, born 25.10.1923, serving in the same unit as Baltrusch.

He claims to have volunteered for the Fallschirmjäger from a Norwegian posting and to have fled out of weariness of service.

13./Fallschirmjäger-Ausbildungs-Regiment Commercy was informed by the undersigned on the evening of 18.5.44 by telephone of the arrest of the two aforementioned.

Using the escape routes of Allied flying personell, pretending to be American airmen, in German uniform, without the language skills? I don’t think the questions which arise here can ever be answered, but did ‘Brown’ and ‘Chetterwood’ really think this plan would succeed? And why ‘Chetterwood’? As far as I can tell this isn’t even a family name, but an area in the Dorset countryside. Where did Baltrusch get the inspiration from?

During the National Socialist era, deserters could expect most severe punishment. On 1 January 1934, the military criminal courts were reintroduced in Germany. In 1935 and 1940, the provisions on the two offences below were considerably tightened:

Unauthorised absence basically constituted an ordinary military offence. The new, stricter provisions turned an offence into a crime punishable by up to ten years' imprisonment. The crime was considered to have been committed if a member of the Wehrmacht had deliberately or negligently been away from the unit for more than seven days (or more than three days in the field) , or had not returned to the unit after being separated from it. The special wartime criminal law regulation reduced the time limit for cases of unauthorised absence to one day (according to the 1940 revision of the law, the time limit for returning after separation from the troops was three days, from October 1944 only one day).

For desertion, the rather forgiving sentencing guidelines of the German Empire had initially remained in force and had provided for the death penalty only in the few cases that were particularly detrimental to the military, but by no means in all cases. However, the Kriegsssonderstrafrechtsverordnung (KSSVO - Ordinance on Special Criminal Law for the War), which was issued before the start of the war, stipulated indiscriminately in § 6: "In the case of desertion, the death penalty or life imprisonment or imprisonment for a period shall be imposed.”

The death penalty however, seemed to be the preferred option; in accordance with the lack of judicial independence, it can be assumed that the Hitler statement "The soldier might die, the deserter must die" had a decisive effect. If the offender turned himself in within a week to continue his military service, the court could reduce the punishment to imprisonment.

According to extrapolations, the Nazi military justice system handed down around 30,000 death sentences; of these, around 23,000 were carried out. However, a recent study by the historian Stefan Treiber arrives at lower figures. A more detailed evaluation of the Wehrmacht criminal statistics revealed that during the Second World War, approximately 26,000 soldiers were convicted of desertion. Looking at the jurisdiction of the field army during the campaign against the Soviet Union, he arrived at a death sentence rate of about 60 % by the end of 1944. The execution rate, measured by the death sentences, was also about 60 %. This would mean that about 10,000 Wehrmacht deserters were executed by the end of 1944. In total, about 350,000 to 400,000 soldiers deserted. This makes for a desertion rate of about 2% out of about 18.2 million soldiers in all branches.

Although the death penalty was often imposed for desertion, prison sentences were also imposed, especially penitentiary sentences, and more rarely also prison sentences. From 1942 onwards, when prison sentences were increasingly served in front-line penal units, a transfer from there to a concentration camp could also take place after a review period. In the late phase of the war, there was the possibility of a pardon, which was linked as a condition to deployment in a military probation unit, where assignments with little chance of survival often had to be carried out.

It is unlikely that Baltrusch and Schille will have escaped the most severe of sentences. The records are silent about their fate.

(Dulag Luft) was located at Oberursel (13 km north-west of Frankfurt-am-Main in Germany) and was the greatest interrogation centre for captured Allied aircrew in all of Europe. The vast majority of captured airmen were sent there to be interrogated before being assigned to their permanent prison camps.

Very interesting. It’s fascinating to find out about this sort of historical information.

Great stuff, Rob! Very interesting article.