Even though I was intending to launch the second instalment of my series on German sniping in the First World War today, I have to postpone this event to tomorrow. Having found some fascinating, new accounts last week, I decided that these would make a wonderful addition to the otherwise finished article.

Pondering about this however, reminded me that one of the most gripping, literary descriptions of a sniper’s work can be found in the writings of none other than Ernst Jünger. In case you have no idea who Ernst Jünger is [I am not sure if this is possible], let me furnish you with the briefest of biographies:

Ernst Jünger was born in Heidelberg in 1895 as the son of a comfortable middle-class family. With a lust for adventure he was bored and uninterested in school life; he soon ran away from home in 1913 to join the French Foreign Legion, briefly serving with his regiment in North Africa, until his father hauled him back home. This experience left him with a lust for combat, and it is not surprising that he volunteered for the Kaiser’s army in 1914. He served with great distinction in the Hannoverian 73rd Fusilier Regiment, becoming a legend among soldiers on the Western Front as an infantry officer and leader of stormtroopers. During his service in Flanders, the Champagne, the Artois and the Somme, he won both classes of the Iron Cross, the Royal House Order of Hohenzollern with Swords and Prussia's highest military award, the Pour le Merite. He spent almost three years in the trenches in the bloody triangle between the north-eastern French towns of Arras, Albert and Cambrai on the Western Front, receiving his promotion to Leutnant in November 1915. Fortunately he was as lucky as he was courageous and it is a sheer miracle that he wasn't killed or permanently crippled. In battle, on patrols and in trench raids, he was hit by 14 projectiles, only three of which came from indiscriminate artillery fire. The other eleven - rifle bullets and hand grenade splinters - were directed at him personally by British or French troops. His company was almost completely wiped out on two occasions. When he was wounded for the last time at Cambrai, two men who tried to carry him to safety on their backs were killed with shots to the head. Jünger found the war to be a supremely transcendent experience, a distillation of the struggle of life, and the core of masculine identity. A passionate and latently-suicidal warrior, pathological narcicisst, writer, biologist, philosopher, mystic, nationalist, anarchist, and consumer of psychedelic drugs, he stands alone among twentieth century writers.

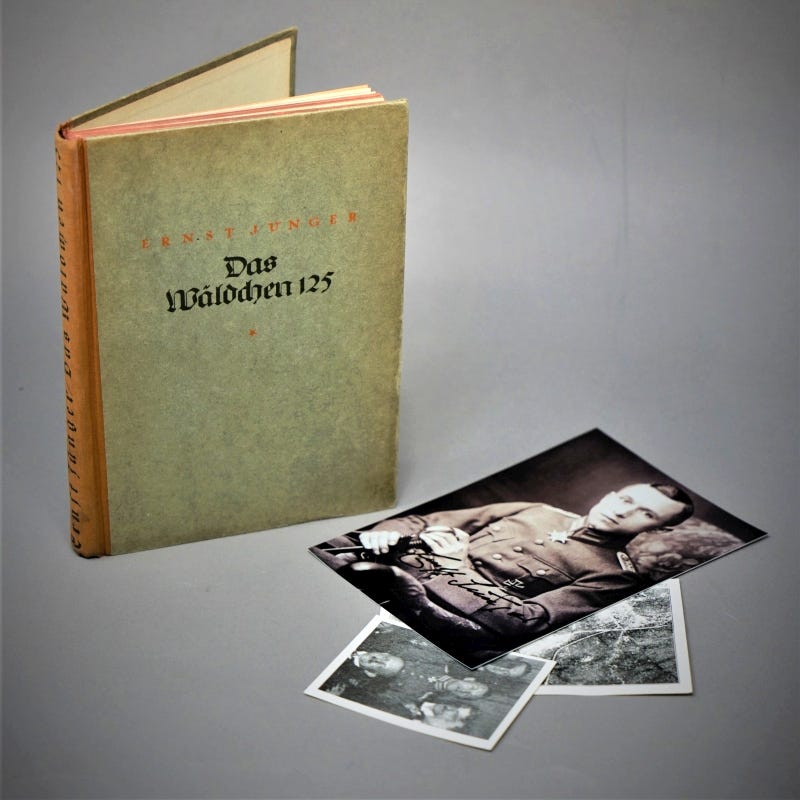

The description can be found in Das Wäldchen 125: Eine Chronik aus den Grabenkämpfen 1918 [English title: Copse 125: A Chronicle from the Trench Warfare of 1918], an autobiographical work by Ernst Jünger, in which he describes the events surrounding the positions in front of Copse 125 at the Somme in excerpts and in an exemplary fashion. An episode already described in Storm of Steel - Jünger's world-famous book about his experiences in the First World War - was elaborated here into an independent chronicle of the deadlocked positional warfare on the Western Front in the last year of the war.

Do we still know the spirit of the hunt in our reserves where no large or combative beast can survive? It has become a sport, a recreation and a dull reflection of the bold deed it once was. Perhaps something of its spirit has passed into the high game, in which chance and the prize still rule supreme, and in which power, masked behind the form of money, is vied for on fields of red and black. For the true gambler, it is not the prize that is essential, but the stake and the throw, where defeat and victory converge into a single emotion. He desires much, he wants to feel the triumph of the hunter and the fear of the prey at the same time. Blessed is he who, in order to experience such feelings, is not dependent on the game, that flat mirror of life and fate! In all great passions, wherever love or combat stir the blood, one feels oneself and the other with it. In these moments of exhilaration one enters into a higher order, the understanding of the brain is replaced by that of the blood, one perceives the person, whom one is facing as friend or foe, as another self. Therefore, the one who shoots at a human being also feels fear, even if it is done from the most secure ambush. It is impossible for him to remain calm, he is gripped by a frenzy which cannot be imagined to be wilder and at the same time more frightening. Philosophical or moral reasons could be found for this phenomenon, but in soldierly terms it is simply an inhibition that must be overcome, overcome quickly, so that no veil covers the eyes, the breath does not pause and the finger can be curled without trembling. There is much premonition in war, if only because war is a matter of the blood and not of the mind. And this time, too, it was more a premonition than a thought that told me: behind this clump of grass, however immobile it may seem in this dead land, there is nevertheless a human being hidden, and although almost two hours had passed, this feeling did not let me rest for a second. It had not deceived me.

Suddenly there was a sound that was strange in this midday field, a scraping clank, like the sound of a steel helmet or a gun scraping the walls of a trench. At the same time I felt a fist digging into my leg and heard a whistling breath behind me. It was H. who had been lying in the same tense attention for these past hours. I pushed my foot back to warn him, and at the same moment a greenish-yellow shadow streaked across the open trench from back to front. The apparition had passed by like a breeze, but had still been clearly visible. A tall figure in a clay-coloured uniform, his head covered by a flat, somewhat crooked steel helmet, and both hands clasped to the rifle, which was hung by a strap around his neck. It had to be the relieving sentry, and now it could only be a matter of seconds before the relieved one would walk past the same spot towards the rear. I took another sharp look at them in the reticle. Only now did the time begin to become endless. Behind the screen of grass a murmuring began, occasionally interrupted by muffled laughter or a soft clattering. Then a tiny wisp of smoke rose up -- now the moment must have come, for the departed had probably lit a pipe or a cigarette on his way. And he did indeed appear, first with the steel helmet, then with the whole figure. He was not as tall as the other, perhaps an Irishman or a London city boy. He was not lucky, because just as he was about to cross the finish line, he turned around and took the cigarette out of his mouth, probably to call back a few words that had occurred to him during those few steps. He was not to get an opportunity to do so, for just then the iron connection was forged between shoulder, fist and rifle butt, just then the reticle cut across the sewn-on pocket that stood out so clearly from the left side of the middle of his tunic as if it were pinned up in front of the muzzle. Thus the shot tore the word from his mouth. I saw him fall, and having seen many fall, I knew he would not get up again. He fell first against the wall of the trench and then collapsed, no longer subject to the laws of life but to those of gravity alone.

Stay tuned for the next instalment of ‘A DIRTY DUTY WELL PERFORMED’ tomorrow.

On tenterhooks!