This is an updated and extended version of an article I first published in print in 2019. It is free to read for everyone, but additional material is provided for owners of a paid subscription of 'THE IRON TIME’.

In March 1917 Germany launched Unternehmen Alberich, a strategic withdrawal to the Siegfriedstellung (english: Hindenburg Line). With this move it shortened its defensive lines by eliminating two salients which had formed in 1916 during the Battle of the Somme, between Arras, Saint Quentin and Norron. It had been aptly named after a figure from Germanic mythology, a cunning dwarven king with strength of 12 men, who possessed the power to turn himself invisible and took the Allies fully by surprise, spoiling all existing plans for a combined and coordinated offensive against the German Army in the spring of the same year. Whereas the French Army under General Robert Nivelles was still able to deal a blow to the Germans at the Aisne and the Champagne, the situation of its British Allies had changed drastically.

Their planned assault, intended as a diversionary action and supposed to draw German troops away from the French area of operations, was reduced to a few minor offensive operations of General Edmund Allenby’s 3rd Army in the area of Arras. During the execution of Unternehmen Alberich the Germans had systematically laid waste to 1500 square kilometres of French territory creating a wasteland of destroyed villages, roads, railway lines and polluted wells. Having to cross this desert of destruction was 5th Army under general Gough which failed to reach the new German defensive lines quickly enough to contribute much to the British main effort. Faced with this situation Field Marshal Haig ordered Allenby to launch a thrust towards Cambrai and ordered Gough to land a blow in the area between Bullecourt and Quéant - a risky move as this blow would have to land quickly if it was meant to remove German pressure on Allenby’s 3rd Army.

The great Clausewitz wrote that in the whole range of human activities, war most resembles a game of cards - according to him it was an interplay of possibilities, probabilities, good luck and bad. For Gough, faced with a lack of functioning infrastructure, horses, heavy artillery and enough time to blow sufficiently large gaps into the German wire entanglements, this had a similar effect to being dealt a 7 and a 2 in a game of Poker. The only thing that he was able to do was to launch an attack on a narrow front and to play a Joker in the form of a handful of Mark II training tanks with which he might just be able to break the wire quickly enough. After that he would have to rely solely on the courage and morale of his Australian troops to win the day. Initially the plan was to attack Bullecourt from two sides on 10 April 1917, in a joint attack by the British 62nd and Australian 4th Division. Yet the assault had to be delayed by 24 hours when the supporting tanks failed to arrive in time. The spontaneous change of plan did not reach all units in time. Two battalions of West Yorkshire Regiment (62nd Div.) attacked only to be repelled with heavy losses. Now a day later, on 11 April the attack was resumed. Yet only 11 tanks had been able to advance in support of it and due to the abortive attack the previous night the German defenders were now on alert, ready and waiting. Ultimately, the Australian attack on Bullecourt on 11 April 1917 would become a costly and tragic failure. The attacking formations of 4th Division (4th and 12th Brigade), had suffered over 3300 casualties, 1170 of them taken prisoner.

During the last 100 years there have been countless attempts to explain this. The most common explanations, ‘the element of surprise had been lost’, ‘there wasn’t enough artillery preparation’, ‘the tanks failed to do their job’ and ‘high command (Gough) is to blame’ all have a grain of truth in them. Others like the story of the ‘impregnable Hindenburg Line’ with its deep network of trenches, dug outs and wire entanglements are less convincing. The most obvious explanation, i.e. the excellence and bravery of the German infantry defending the Hindenburg line, is barely talked about. So how did the battle pan out for the German defenders, what were their experiences? We are lucky that the original records of 27 ID and its subordinated formations more or less fully survive, which allows us to highlight a few central themes of the battle by using personal and official German testimony.

THE MYTH OF THE SIEGFRIEDSTELLUNG

Before taking a look at the German soldiers' experiences during the battle, it is important to talk about what exactly they were defending.

Siegfried Dragon Slayer, invulnerable after bathing in the dragon’s blood, is the mightiest hero of the Norse and continental Germanic traditions. He wields the magical sword Balmung and has the power to make himself invisible by using a cloak he took from the dwarven King Alberich. Siegfried Position is thus a fitting name for the mighty defensive line that Gough was tasked to crack open. It was modern, having been designed based on the German experiences of the battles of Verdun and the Somme. In it the doctrine of in-depth elastic defence had been translated into a complex system of concrete and barbed wire. Two lines, each one consisting of a series of deep trenches, interspersed with bunkers, pillboxes and other nests of resistance. All of it adapted to the topography and geography of the land and tweaked to allow for active and passive tank defence. Its propaganda value certainly equalled its enormous building costs, yet by March 1917 it was - in many places, still far from being completed. Its defensive qualities were in many places as real as the Germanic heroic legend of the Dragon Slayer.

During the same month Generalleutnant Otto von Moser, in command of Gruppe A of 1. Armee (XIV. RK) wrote a report about the defences at Bullecourt: ‘Sadly my impressions about the alignment and the state of development of this defensive line emblazoned with the nice and hopeful name of Siegfried are not entirely pleasant. The position itself is unfinished and negative experiences have been made with construction management by civilian engineers. Illusionary patchwork along the roads and villages. In other, less accessible places, little or nothing or things unsuitable and unfinished. Of the latter, right in the centre of the forwardmost trenches, a large number of construction pits for concrete dugouts, the completion of which has not been achieved. The men are, without question, fairly disappointed’.

He wasn’t alone in his judgement. A plethora of similar and more devastating reports exist. The commander of Gruppe Arras (IX. RK), Oberstleutnant Albrecht von Thaer expressed a similar view. For him the Siegfried-Stellung was ‘nothing but an enormous trench’ behind which ‘nothing had been finished’. On 3 April, the Generalkommando of XIII.AK reported that ‘major parts of the position had to be built anew, because local staff responsible for the construction of the reverse slope positions had ignored the requirements of observation’. Reports compiled by 199. Infanterie Division and 22. Reserve Division on 31 March 1917 criticised the ‘total lack of tactical understanding and consistent construction plans’ among the engineering staff.

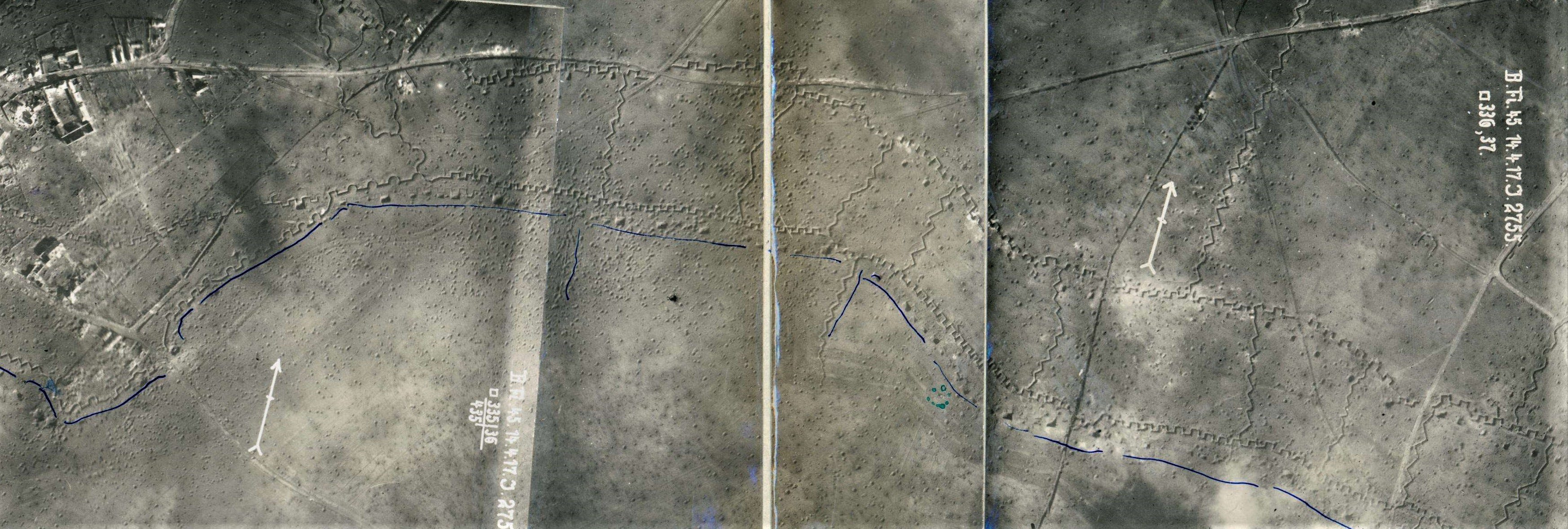

In stark contrast to these reports the sheer scale of the construction works, clearly visible from the air, and perceptions on what the Germans were in the process of building, led to an Allied portrayal of the Siegfriedstellung as an impassable barrier. The myths about its importance still live on today. Yet, just as the dragon blood hardened skin of the hero Siegfried was vulnerable on a small spot on his shoulder, the Siegfriedstellung, as substantial as it was, was far from being impassable. The regimental reports of Grenadier-Regiment Nr. 123 (GR 123) and Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 124 (IR 124) on the defensive works and their effects on its outcome of the battle on 11 April state that: ‘barbed wire entanglement in front of the first line was built very well’ and served to ‘stall the enemy advance considerably’, but there was a lack of ‘strong points in the intermediate zone’ and although ‘deep dugouts had served well to protect the men from shellfire’ they had, in many cases been ‘too far away from the forwardmost trenches’. This and the lack of supply storage points in the combat zone had caused ‘critical delays’.

THE DEFENDERS

Facing the Australians in the sub-sectors of Riencourt, Bullecourt and Quéant was the 27. Division which was one of the finest and most capable Divisions of the German Army. The 27. (Königlich Württembergische) Division, to give it its home kingdom’s title, had fought its first major battle at Longwy in August 1914 before forcing its way across the Meuse and taking Mont-Montigny. In the first battle between Varennes and Montfaucon it had chased the French 3rd Army into the Argonne forests where the division engaged in positional warfare from late September 1914 to the Winter of 1915, when it was transferred into the trenches along the River Yser in Flanders. In July 1916 the Division fought in the Battle the Somme in the defence of Guillemont. 27. Division - with Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 120 (IR 120), Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 124 and Grenadier-Regiment Nr. 123, artillery and pioneer elements - was an elite formation with an impressive combat record. In the Winter of 1916/17, with the introduction of the German Army’s latest combat regulations ‘Grundsätze für die Führung in der Abwehrschlacht’ ['Principles for Conduct in the Defensive Battle'] and an associated restructuring of its Divisions, the 27th was designated as ‘training’ division. It would become the first to be trained in, and trial the new tactics and latest combat methods running manoeuvres and courses during the first quarter of the new year. It is quite safe to say that there could have been no formation more ideally suited to stand its ground in the lines at Bullecourt.

11 APRIL 1917: BATTLE

There is no doubt about the fact that the attack of 11 April didn’t come as a surprise to the German defenders. The attack of the West Yorkshire’s of 62nd Division on the preceding night (which had caused 162 British casualties) had alarmed them, although no-one was able to make sense of it: ‘On 10 April the enemy attacked northern sector with a battalion of the 62nd Division from the direction of Ecoust. What purpose he hoped to achieve with this sortie is not discernable.’ (27 ID, situation assessment). Nevertheless what it did achieve was to put the whole of the German frontline into full alert. Generalmajor Heinrich Maur, commanding 27 ID, issued an order in which he pointed out that ‘large swarms of enemy riflemen followed by columns of infantry’ had been seen taking position behind the railway embankment in front of Bullecourt and that the enemy was ‘still occupying this position in strength’. Further enemy attacks ‘had to be expected’. At around 2am (German time) patrols working in the German wire entanglement could hear ‘strong engine noises’, but didn’t take much notice of it mistaking it for that of transport lorries. Heavy Allied artillery fire lay on Bullecourt and Riencourt, the defensive positions and trenches themselves ‘initially received only light fire’. At 4:30 sentries spotted ‘the English working in the wire entanglement’ and 15 minutes later - out of the twilight: ‘(…) a number of firing tanks moved against the sector. English assault columns in five waves advancing with the tanks, followed by more infantry in closed order. Patrols and sentry posts fell back in face of the tank fire’ while at the time ‘low flying aircraft raced overhead giving horn signals’.

‘The machine guns were mowing down whole lines of Englishmen. The English though charged forward in such masses, that the thin ranks of the garrison of the forwardmost trench in section C1 stood powerless against them.’

These aircraft were taken under fire by the German infantry lining in the trenches. Gefreiter Wilhelm Bieler of IR 120 later wrote in his diary: ‘the English aeroplanes flew over our position. So low that we could clearly see the heads of the pilot. We all opened fire with our rifles and one plunged into the earth right in front of our trench, where it shattered into several pieces.’

The regiment claimed two aircraft shot down in that manner on that day. Yet this resulted in a soft reprimand after the battle, when 27 ID ordered that from now on: ‘wild, uncoordinated infantry fire on low flying aircraft is to be avoided’ and that ‘only specifically designated groups of men under command of an officer’ were to engage aircraft in that manner. The wreck of one of the aircraft brought down is clearly visible in later aerial photographs of the area.

By then German defensive artillery fire had been called in, although this was: ‘too weak to cover the whole width of section C’ (IR 124). Waves of Australian infantry surged at a quick pace towards the German lines. The outnumbered German infantry: ‘to avoid being slaughtered in the deep trenches from above, immediately jumped onto the parapet and directed a lively fire into the English masses and threw hand grenades. The machine guns were mowing down whole lines of Englishmen. The English though charged forward in such masses, that the thin ranks of the garrison of the forwardmost trench in section C1 stood powerless against them. Each man had fired up to 70 cartridges. When the enemy reached the trench, close-in combat began. Hundreds of hand grenades were thrown into the English assault columns. The English pushed on sharply, butchering the small garrison of C1 including a machine gun crew. A total of 20 men of the 1st company were killed and 49 wounded. Only a small number managed to escape the slaughter.’

Musketier Johann Baierlein described this in a letter to his sister a month later: ‘The English fell upon us and I have to thank our Lord that I managed to escape with my life. Not even the wounded they spared. Rest assured though that we later repaid them in kind. This war brings out the worst in all of us. Pray and be grateful that you are all safe at home.’

During an unsuccessful counterthrust Leutnant Mohr, commander of 1./IR 124, was killed by a hand grenade. The 30 or so survivors fell back into the second line. In section C4 and C5 of the German line Australian troops achieved another break-in. The after action reports of IR 120 stretch the fact that the Australians had been able to exploit the ‘momentary confusion and uncertainty which seized the fighting troops when the tanks appeared’.

The Australians had already begun consolidating their gains, using picks and shovels to turn the trenches they had taken, some had even advanced further, into the second German line. At 8:15 already Oberst Rudolf von der Osten issued orders for an organised counter attack to the reserve companies of IR 124 and to assault groups of GR 123 and IR 120. The would attack from three sides, one group from the front while the others were to roll up the enemy held positions from the left and right, a ‘roll-up’ manoeuvre which the regiments had trained and exercised for numerous times. 45 minutes later the counter assault commenced and after brutal and intense hand to hand and close quarters fighting the battle slowly fizzled out.

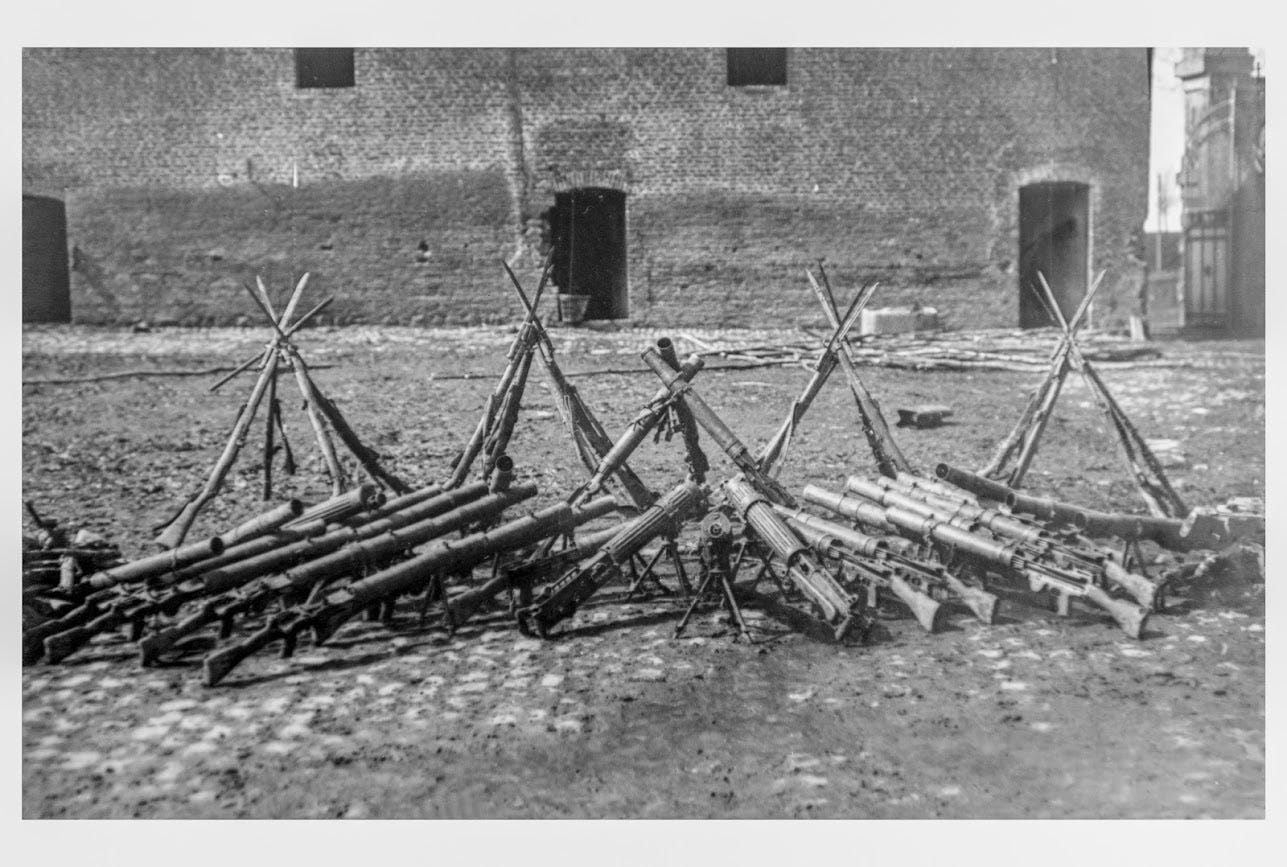

‘Our positions were filled with dead and wounded English. In front and inside the wire they lay in piles. Having fought bravely, they had ultimately been let down by their own, having been unable to push further forward due to lack of reinforcements. We have captured over 400 rifles and 60 machine guns and over 1000 English have been taken prisoner.’ Leutnant Herzog of IR 124 later wrote to a friend in Bad Cannstatt.

A day later 27. ID announced that ‘4th and 12th Australian Infantry Brigades have been wiped out’. 27 officers and 1137 other ranks had been taken prisoner, 9 tanks had been destroyed, 2 aircraft shot down, 53 machine guns and an enormous amount of hand grenades, rifles and ammunition captured and in front of the position ‘the English dead lay piled up high’.

TANKS AT BULLECOURT - THE GERMAN PERSPECTIVE

After their defeat on 11 April, Australian opinion was unanimous that it had been the failure of the tanks which had caused the disaster. Of 11 tanks fielded, nine tanks had been destroyed, seven in or near or in the German lines. The tanks themselves however, so the story goes, mainly ‘failed’, because they had been Mark II training tanks, covered with un-hardened steel.

Of those tanks which did manage to reach the German lines, one deviated from its course when it was showered by German machine gun fire. It then suffered mechanical difficulties and returned to the railway embankment. Another tank also swung to the right and crossed the first trench opposite Grenadier-Regiment Nr 123, about 450 metres to the right of the attack front and was knocked out by machine-gun and Minenwerfer fire. Another reached the German lines, entangled itself in wire while crossing the first trench and was knocked out by Minenwerfer fire. The last tank of the group was about 2 hours late and followed a similar path to the first. The four tanks comprising the left-hand section were late and two were knocked out short of the German trenches; the third tank arrived after the Australian infantry had reached the German positions and silenced a machine-gun firing from Bullecourt. The tank was hit twice, returned to the railway and was hit again. The last tank had ditched but one of the tanks that had veered off course and then returned pulled it free and towed it over the railway, by when it was 6:30 a.m. Under the impression that the Australians were in Bullecourt, the crew drove over the German trenches and into the village where it suffered an engine failure. The surviving crew dismounted and got back to the railway. As tanks were immobilised, German artillery deluged them with shells and all but two were destroyed

Those tanks that didn’t break down or were destroyed by artillery before managing to get close to the German lines now began to engage in earnest. And - contrary to the commonly accepted version of events, they did so with great effect. For most, if not all German soldiers, facing them would be the first time they would come face to face with the steel beasts. And despite the fact they were picked off one by one by artillery and other weapons the MK.II tanks performed well and were very effective. This is clearly evident in the surviving German testimony of the day.

Grenadier-Regiment Nr. 123 later reported that: ‘Shortly after 5am a patrol spotted a tank in a distance of about 600 metres in front of our wire entanglement.’ [D26 799, commanded by Lt. Davies] (…) It approached directly, taking the shortest route towards the wire with a speed of about 3-4 km/h. Arriving there it briefly halted and opened fire on our trench with machine guns. Then it drove along the wire towards the right, firing constantly. After a few 100 metres it turned and broke, without any difficulty, through the triple line of 10 metre deep iron wire and stake barriers. It halted at the furthermost trench, pouring flanking machine gun and cannon fire into the trenches on both sides. The trench defenders, pre-warned about the tanks arrival, had taken cover behind the traverses. This way casualties could be avoided, but further away - in the section of the neighbouring company, a number of Grenadiers were wounded.’

The tank, still firing, then rumbled on, crossed over the firing trench towards the communication trench and then suddenly halted ‘if voluntarily or forced has not been found out’ (GR 123 war diary) - between the first and the second line. From the start, it had been taken under regular rifle and machine gun fire which failed to have any effect. When it approached the second line it was taken under fire by a light machine gun manned by Leutnant Schabel, commander of the regiment's 3rd machine-gun company. He had: ‘brought a machine gun into position a few hundred metres in front of the KTK and had opened up at the tank from a distance of about 150 metres firing 1200 rounds of K-ammunition (steel core) into its side (of which 77 perforated as later counts showed). The tank was at that point still firing lively with its machine guns and two 5.5-cm QF cannon. It then turned, probably because it had taken a number of effective hits, towards the left in an attempt to face the machine gun with its more heavily armoured frontal side. Shortly after this its fuel tank received a number of hits. This resulted in a fire and an explosion of the ammunition stored inside the tank’.

Seven of the crew died in their vehicle, five were taken prisoner. The light Minenwerfer of the regiment had also taken the tank under fire and ‘a number of impacts and air bursts close to it had been observed’. Later evaluation of the wreck showed that this had led to further damage to the tank.

IR 124, which bore the brunt of the fighting on that day, found ‘several tanks driving back and forth along the front of the wire, shooting down everything in range.’

The regiment’s after action report stretched the fact that ‘it was impossible to hold out in the fire of the tanks, from each of which six machine guns raked the parapet of the first trench, causing severe casualties to 10th and 11th company’.

‘Without protection’ the war diary of II./124 goes on to explain, ‘the men stood in the trenches, not knowing how to get to grips with the monstrosities’ and the German companies were forced back into the second line. In front of the regiment’s line, one of the tanks: ‘drove into the wire entanglement where it got stuck. Driving desperately back and forward in an attempt to free itself it finally stood still, but continued firing’. It was finally taken out of action by four Minenwerfer shell hits (firing with a flat trajectory from a range of 450-500 metres) and by the fire of a machine gun. The crew tried to escape and was killed in the process. Another tank, that had one of its tracks blown off by a Minenwerfer shell, was immobilised.

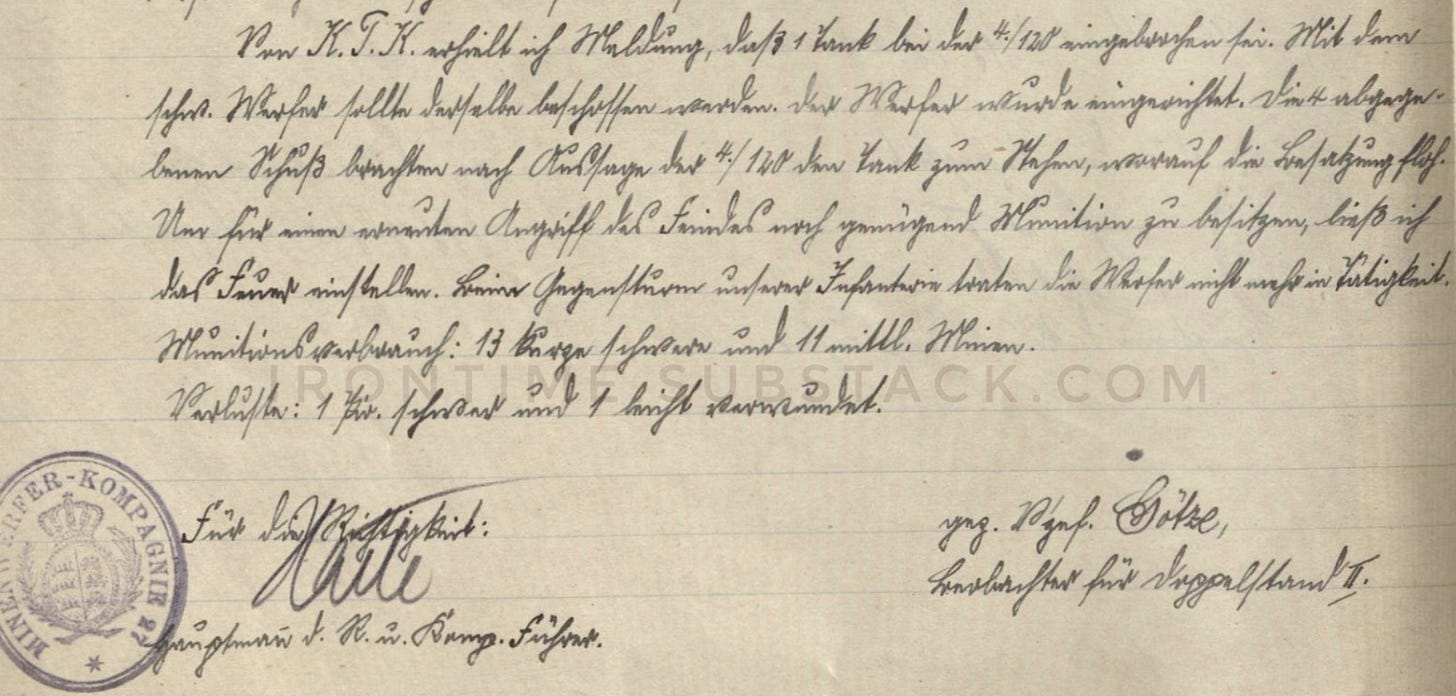

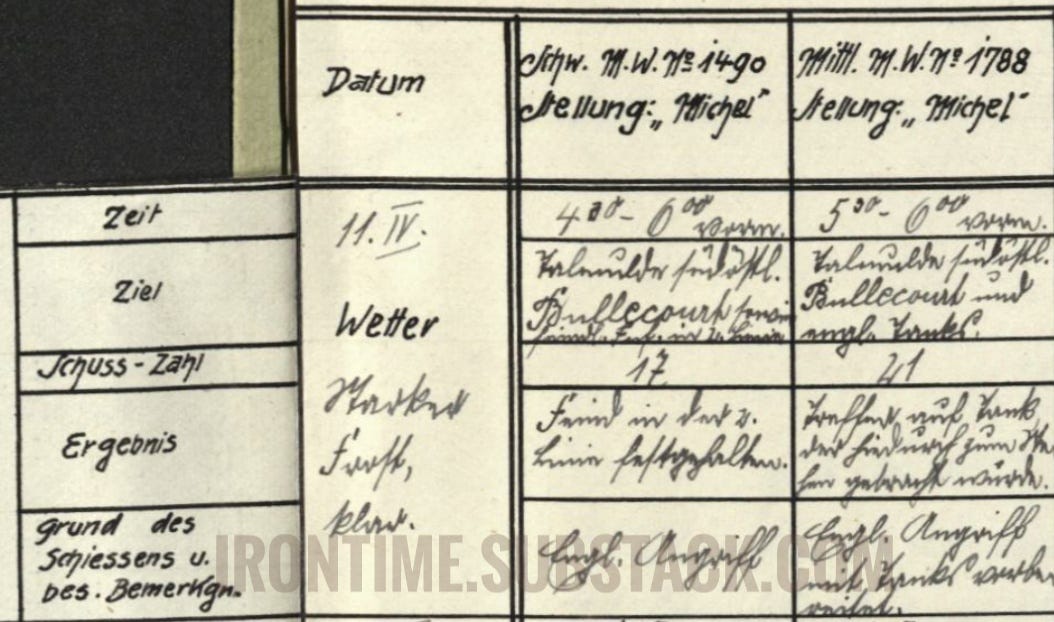

Few things in history are as detailed and thorough as a German war diary, and because the records of 27.ID and its subordinated formations survive more or less in their entirety, we are even able to say who fired the tank-killing Minenwerfer shells. The leader of Doppelstand II [a firing position for two Minenwerfers] in the Michel Position, Unteroffizier Hans Götze, in command of one heavy and one medium Minenwerfer [Serial Nos. 1490 and 1788 - the reports are indeed that detailed], had just run forward to the command post of Hauptmann Schaidler, the KTK [combat troop commander] of IR 120, to make a report and to inform himself about the situation at the front, when the approach of three enemy tanks were reported. His combat report stated that he: ‘was told by the KTK to go back and take [the tanks] under fire as soon as we could identify them visually. Upon my return the heavy Werfer fired 3 shots on the 2nd Line. I observed the impact of our mines. The first one was 20 metres too short and too far to the right, the others were right on target. The medium Werfer fired another 5 rounds on enemy infantry reinforcements. From the KTK I received the report that one tank had broken through at 4./120. The same was to be taken under fire with the heavy Werfer. The Werfer was set up. The four shots fired, according to the infantry of 4./120, brought the tank to a standstill whereupon the crew fled.’

This first documented tank ‘kill’ with a mortar-type weapon, was also neatly documented in MWK 27s war diary: ‘medium M.W.No.1788 - time 5:30-6:00 am - target: depression south-east of Bullecourt and enemy tanks. Rounds fired: 21. Effect: Hits on tank which thus was brought to a halt.’ It is interesting that while Götze claimed that ‘1490’, the heavy Minenwerfer had taken the tank out, the firing log awards the kill to medium Minenwerfer ‘1788’.

I.Btl.120 - Command post a Nord, 17 April 1917 to M.W.K.27

May it be brought to your knowledge that the Vizefeldwebel Götze, Werfer commander during the fighting of 11.IV.17, has greatly distinguished himself. He knew how to bring his Werfers to bear on the advancing masses of Englishmen in the section 124. The outstanding effect could be observed from my observation post. Suddenly finding himself under attack he bravely defended his M.W. position together with the infantry. During the later course of the battle, after the attacks had been stopped, he took the enemy under well-aimed, regular fire. As such he played an essential part in repelling the English attack and in the retaking of section c. The most special deed of this brave Vizefeldwebel however, was that he took it upon himself to establish communication with me and that he then took the time to inform me about possible uses and performance of his Werfers. A uniform deployment of all forces for the counter thrust was thus assured. I commend Vizefeldwebel Götze to be decorated with the Iron Cross 1st Class. - Schauller, Hauptmann und Bataillon leader I./120

Three tanks approached into the general direction of IR 120 turning towards Bullecourt: ‘Two were finished off by artillery before they even got close, but a third managed to cross over the wire entanglement and our position before driving into Bullecourt (….) when it tried to cross into Hendecourt it also found its destiny. A direct hit by a mine (mortar shell) caused it to explode’.

AFTERMATH

All German regimental accounts universally agree that it was the tanks that had enabled the Australians to momentarily break into the German lines. Their effect was valued and understood. The German Army did not (as is often claimed) learn ‘the wrong lessons’ from facing MK.II tanks. K-Munitions (steel core) had been effective and were later effectively used against MK.IV tanks. It was understood that effective tank defence was and would be a combined arms effort and that artillery played a key role in it. Tanks were technically unreliable, slow and could be defeated by well-supported and equipped infantry and artillery. This only changed with the mass deployment of tanks in combined arms attacks later in the war. If the German Army had learned a wrong lesson during the Battle of Bullecourt it was that tanks could be effectively stopped by ground obstacles, pits and trenches with a width of 2,50 metres. A fatal lesson that would continue to be taught in the months to come.

‘I fired at it myself, but I could just as well have thrown peas at it.’

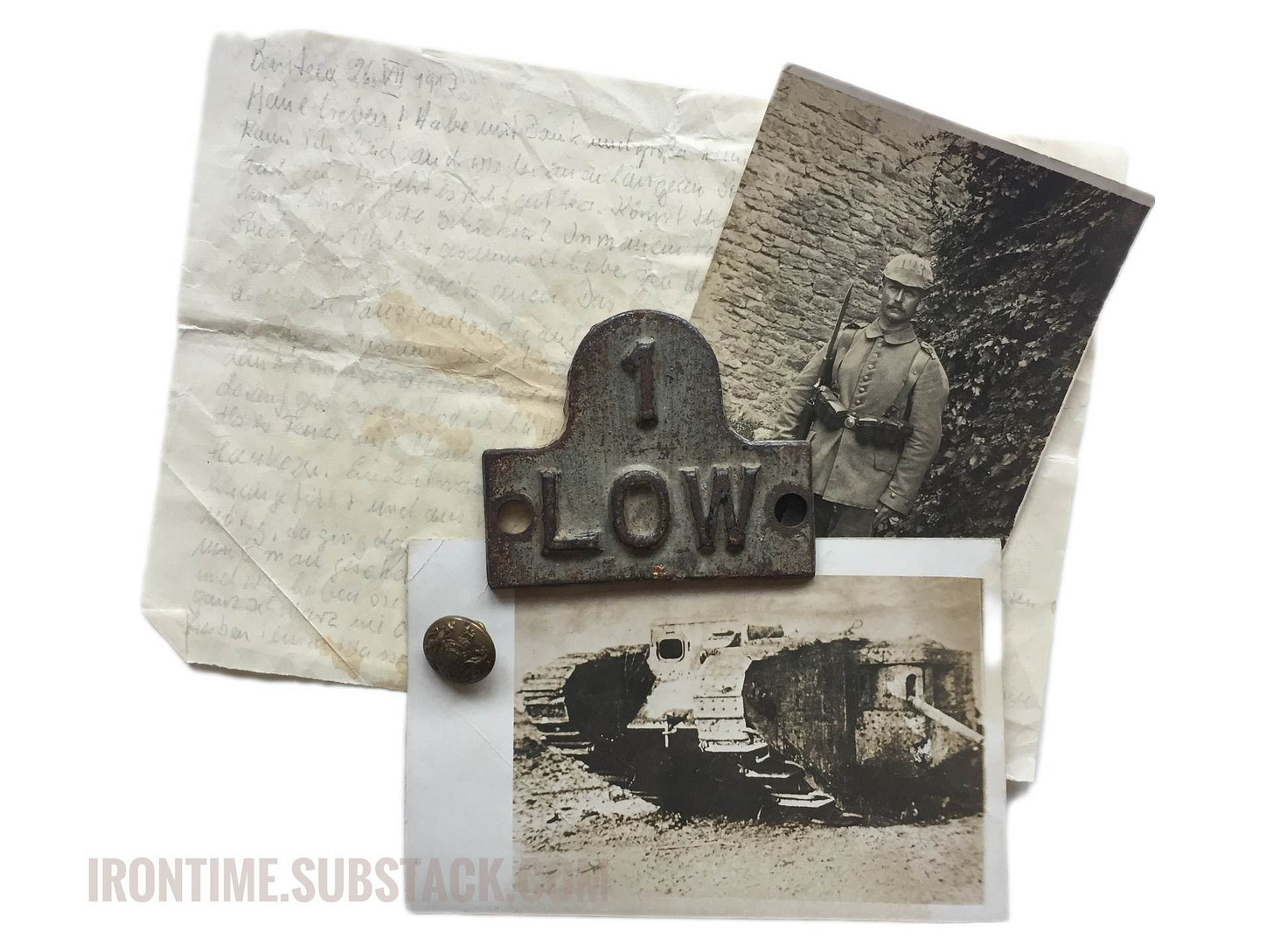

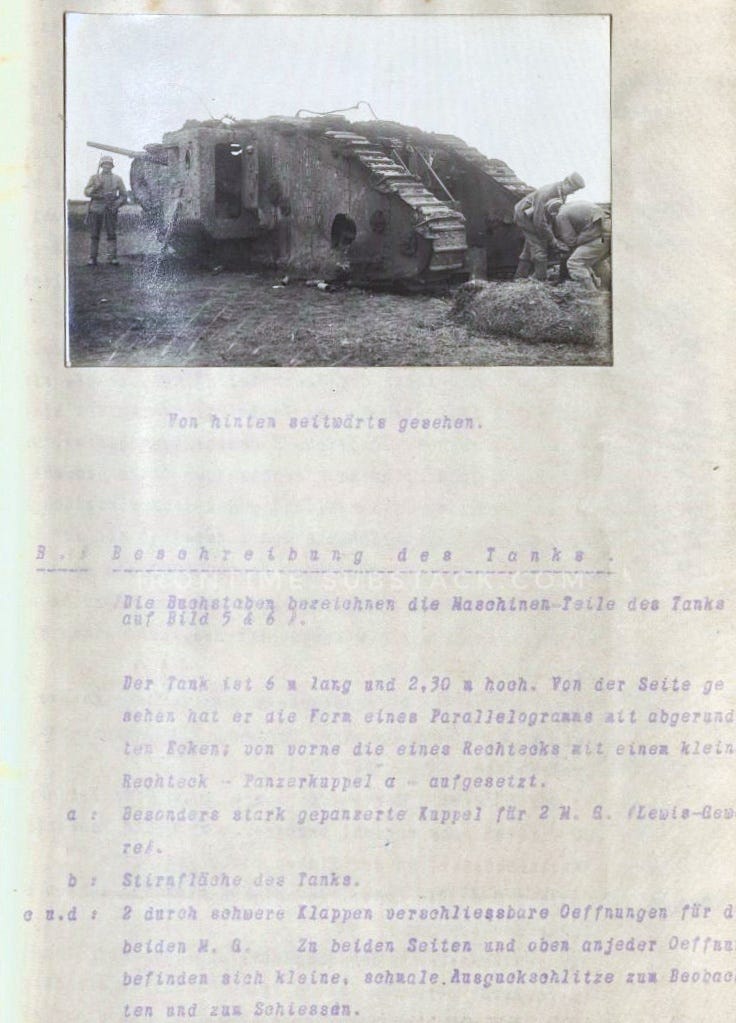

After Bullecourt the German Army, for the first time, had unrestricted access to a number of British tanks and only hours after their destruction, the wrecks still hot from the fires which had destroyed them, German troops started taking a close look at the defeated giants. The tanks of Bullecourt became the most photographed of the war, every soldier felt magically drawn to them and first photographs taken of them were copied, sold and sent home to families in Germany in enormous numbers. A soldier of GR 123, whose family name is unknown, sent a parcel of souvenirs home [see photo below] which included the gear shift indicator plaque of D26 (Lt. Davies) destroyed by Leutnant Schabel:

‘In this parcel you will find the new pieces I have collected here. You can give the English helmet to Georg as I already have one myself. The plaque is from one of the English armoured cars, which are known there as “Tank” and which was shot to pieces by the regiment near Arras. I fired at it myself, but I could just as well have thrown peas at it. Only when it was fired at with mines did it turn away and so exposed its flank. A Leutnant from the MGK brought up a machine gun and fired at it from close range. It took nearly 2000 rounds before the beast caught fire. Such an infernal spectacle has to be seen to be believed. The crew had to get out and we welcomed them. The poor devils were black from the oil. Some were severely burned and wounded. We then gave them water and bandaged their wounds. We then all got out to take a closer look at the monster. It is about 7 metres long, has a height of 3 metres and is made completely of iron. It is armed with two heavy guns and 4 machine guns. The side was shot to pieces by bullets. The inside was still too hot from the fire. Next to the Tank lay a dead English officer from whose jacket I took the button. On the following day we buried him behind our trench. Inside, Heinrich and I later found a few more things. Inside the machine it is similar to what it must be like in the inside of a ship. The Captain sits in front while the gunners sit on the sides. The regiment slaughtered two of these infernal machines on that day. We too suffered casualties, but they were light. The fear these machines cause is their biggest asset. When this has been overcome their effect is small. Please keep all the items for me.’

Only two days after the battle, the first detailed technical evaluations of the tanks were created and published in a report which contained the first German photographs taken of British tanks. It made note of the effect that defensive weapons of all kinds had on them, described weaknesses as well as strengths and formulated, for the first time, strategies to counter them.

‘12 April 1917: (...) the ‘Panzertanks’, which have fallen into the Division’s hands during yesterday’s attack, are to be brought in. 1 Unteroffizier and 1 man of the company were commandeered to do so. They tried, but as the ‘Schuppengürtel’ (lit: scale belt) which serves to drive the vehicle forward had been destroyed by a shell, it was impossible to do so. The tanks were examined, sketches were made and important apparatuses dismantled and passed on to the Kdr. der Pi. 27.ID (Pioneer High Command, 27ID).’ - War diary of Pionier-Bataillon 13

The Allied artillery preparation had been recorded as efficient, but ‘weaker than expected’. 27 ID blamed this on a British lack of ammunition, not on a lack of guns.

In advance of the attack, severe casualties were inflicted to the Germans by ‘highly concentrated Phosgene’. On 10 April, IR120 had ‘a full company was incapacitated by gas. 20 men were killed by gas poisoning’. On 11 April, 50 of the 264 wounded men treated in the main dressing station were suffering from severe gas poisoning. According to later evaluation gas masks could have offered protection, but had not been put on in time.

For the Australians the day would enter the history books as one of their costliest. Casualties had been severe and on no other single day of the war had so many Australian soldiers been taken prisoner. For the Württemberg soldiers of 27 Division though, the day had been a great victory and proof that the new tactics they had learned to employ were working. A feat rightfully described by some of the captured Australian officers as a ‘splendid action’. The action that would follow during the second Battle of Bullecourt in May would have a different outcome however, but this is a story I can hopefully tell another day.

Report of the commander of Infanterie-Regiment ‘Kaiser Wilhelm’ Nr. 120

In my eyes the initial failures during the Battle of Arras are based on the superiority of the enemy artillery. I can’t judge from personal experience as there was no such initial failure in the sector of Infanterie-Regiment Nr 120. On 10 and 11 April 1917, the regiment had held its positions (700 meters north-west of Bullecourt up to and including the eastern side of Bullecourt) in the face of heaviest artillery fire, strong infantry attacks and tanks without fail and has played a significant role to thwart an enemy breakthrough in the neighbouring sector by rolling up the furthermost trench with hand grenades and in the main by MG-fire from the area north of Bullecourt. Thus I see it as important that the distribution of machine guns behind the furthermost line also takes the defense of neighbouring sectors into account and not only that of one’s own section. The tanks have only caused confusion at their first appearance. It’s been clearly shown that their armour can be penetrated by machine guns firing K-Munition. Here at the front of 27 ID they are not being feared anymore, although they can be quite a nuisance when driving along between the trenches and the obstacles. It is valuable to try to get them with light, rapid firing guns and munitions with high penetration before they reach the obstacles. In addition their movement mechanism doesn’t appear to be working without fault. New experiences with combat methods were not made. But I have again come to the conclusion that the most important things in the fighting of today are not tactical variations and regulations, but - next to making use of all available technical means - good nerves, presence of mind and common sense. One can’t claim that all means of today's technology have been used in the defended sector. The battalions however, arrived in a fresh and rested state. Thus the men have endured the very effective and precise fire of the English artillery, which admittedly didn’t last that long, and even the nerve-wrecking gassing, without fail, even though one company was made fully hors de combat by it. If the nerves weaken, then there is always the danger that the men, even if usually excellently disciplined, well trained and superb moral, will try to avoid being engaged in close combat. The moral can only be partially influenced by suggestion and is mainly based on physical living conditions.

The basis of strong nerves is ample sleep, no overburdening with manual labour like digging trenches, spending not too much time in dugouts with bad ventilation and meagre lighting. To keep the spirits of the men up it is important not to demand exhausting services from them where they are evidently not required by the conduct of war. Wherever possible the troops need to rest before and even during major fighting. This, and their timely relief is more valuable for the achievement of success than any leadership order, even is right and proper, which is only taking the elements of space, time and units designation into consideration. It is clear that the grinding influence of combat has the deepest effect on the leaders in the furthermost lines and as such, the reports arriving sent by them are often exaggerated. It is natural, knowing how much the higher leadership focuses on maintaining an ‘excellent moral’, that mid-level leaders are often tempted to portray the state of their men better than it actually is. It is maybe worth checking if certain failures can be explained by this fact.

That the sector held by the division was very wide (5 km) didn’t result in any disadvantage. On the other hand the infantry regiments had to activate their reserves very quickly, and if they had been unable to achieve success with their own means, then battalions of another division would have had to be called up for support. The enemy attack however was met with a uniform, flexible leadership which, free of model formula, was able to shift troops by battalions and companies to where the moment demanded their presence. The often narrow, tubular and often wildly and awkwardly curved trenches formed by the necessities of positional warfare, make any kind of uniform command difficult indeed. Only in a wide regimental sector as we found it here, can the regimental commander take a little command influence. In a normally structured system (three lines deep), he is more or less redundant. The battalion and company commanders have a better situational awareness, right from the start according to schedule and during battle. He and his company commanders can act and react independently. The regimental commander doesn’t really have any troops at his personal disposition, the battalion resting is usually a group reserve, tied directly to the orders of the Brigade or the Division. Once the combat troops in the frontline are beaten, he has no option but to wait for the help of others and to afterwards take responsibility for failure. As such he is often not a tactical, but more of a policing and regulatory officer. The fighting at Bullecourt has also shown the layout of the furthermost line is extremely unfavourable. ‘Bastions’ are misunderstood traditions from the days of short firing distances. They devour enormous numbers of infantry without any apparent advantage. Instead they are being flanked. For the enemy artillery however such a fortified bastion village offers great amusement, as they are able to gas the whole thing with a few shots. The quite considerable gas casualties of the regiment have been caused by the above.

Positional construction: Obstacles, dugouts and trenches - superb, but sadly not present in this sector. The eyes of the superficial observer are being blinded by faultless trenches, but there were only few dugouts, concrete shelters in particular were not finished at all. The planned command posts of the battalion leaders were already under quite severe artillery fire while they were being built. If the work parties are then frequently exchanged, it doesn’t come as a surprise if only a minimum of the work has been done. In addition the concrete-reinforcement and similar construction troops, not subordinated directly to the infantry, see themselves as Army troops, only briefly attached to the infantry and on a flying visit in a guest role only.

Finally I think I need to point out that the voluntary withdrawal from a threatened, but still more or less usable position into an unfinished, rearward position, doesn’t have a positive influence on the men. The common man has a keen sense of observation. He will have more understanding if he is asked to hold his position at all cost instead of suddenly, after a voluntary, ordered withdrawal, finding himself in an even worse position, which requires additional work from him, while at the same time the result of his previous work is left to fall into enemy hands. A repetition of this, against all advice, will damage the trust the common soldier has in the leadership.

Signed: Oberst von Gleich

‘AUSTRALENGLISH’

In German records, both personal and official, soldiers of the British Army and from the Commonwealth, men from Australia, New Zealand and Canada were almost universally described as ‘Engländer’ (English), yet the formations these men served in were correctly named according to their origin. For the German soldiers in the frontlines the finer nuances of the cultural diversity they faced across the barbed wire was of little importance and ,in most cases, not really understood. A rare exception to this rule was Gefreiter Konrad Striebel, who reported about the battle on a field postcard to his parents on 13 April. He had a better understanding of the men he faced and he seemed keen to educate his parents about it too when he wrote: ‘The attackers were English from Australia. You have to know that they are the descendants of English convicts who were sent to this country for their crimes! They are coarse and sturdy fellows, but we have taken a large number of them prisoner.’ A clerk keeping the war diary of Feldlazarett 255 (field hospital) based in Bugnicourt, revived an outdated and old fashioned German word on 13 April when he noted: ‘Arrival of an additional 20 wounded, among them 7 Australengländer (Australenglish)’. A staff officer of 53. Infanterie-Brigade, Hauptmann Wilhelm Rieger wrote to his wife: ‘Registration and interrogation of the Australian prisoners taken at Bullecourt is progressing well. In general they are all quite cheerful and happy that the war is over for them. They are all tall and well-built fellows, but they lack formal education. I have encountered several who are not able to read and write. The officers happily answered all my questions even though they had initially claimed they would not. They are an interesting people, who don’t have much sympathy for the English.’

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to THE IRON TIME to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.