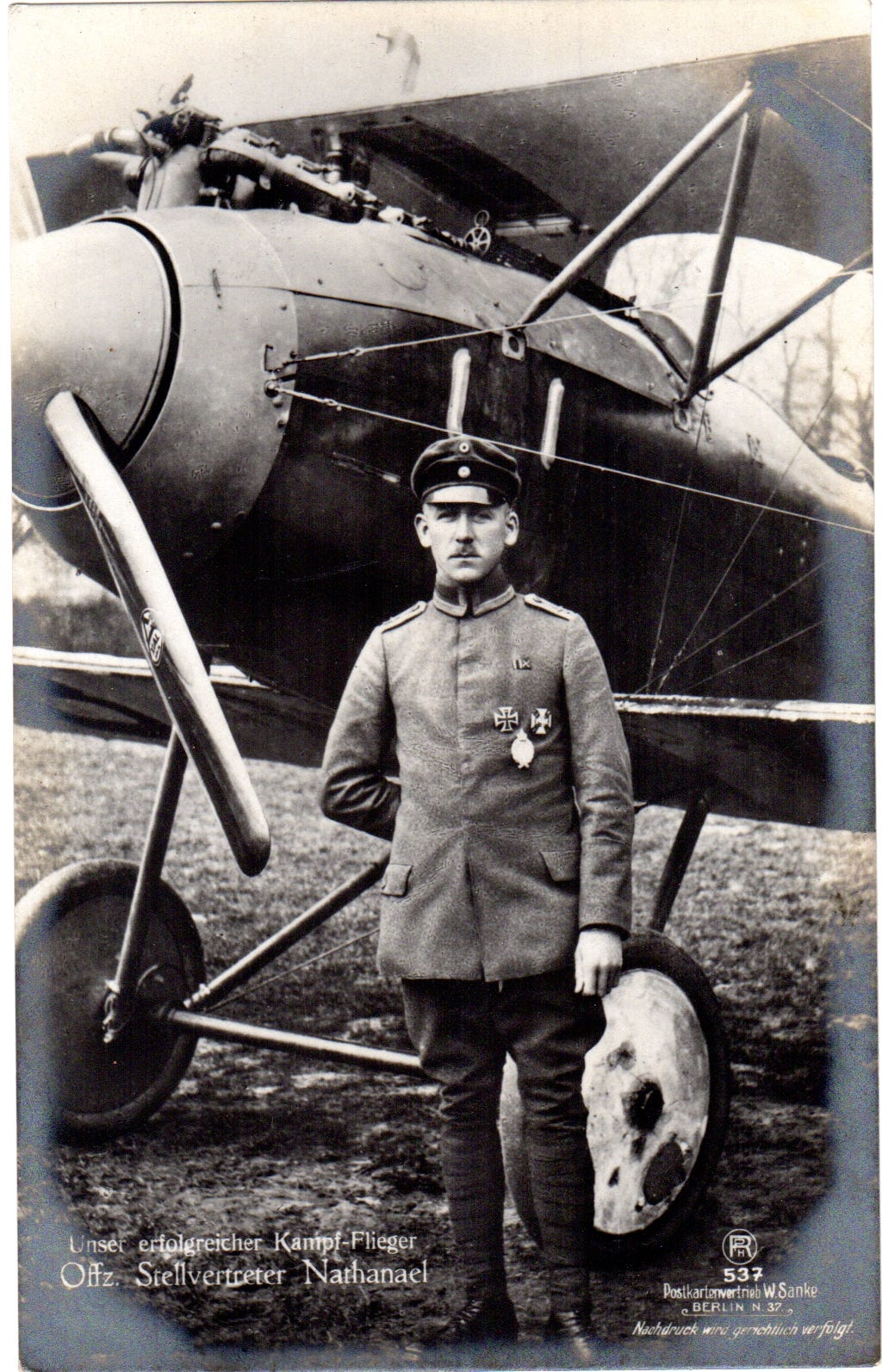

Emil Edmund Nathanael came to my closer attention several years ago, when I managed to acquire a signed portrait photograph of him in an estate sale in northern Germany. The unique photo, which since then has been published several times, still ranks among my favourite collection pieces and I have used the time since to gather more information about the man, who shortly before his violent demise on 11 May 1917, was on track to become one of the shooting stars of the German air service. Information about him is choppy at best and the few reliable facts gathered by aviation historians like Lance Bronnenkant and Neil O’Connor, have been much diluted by myth and hearsay.

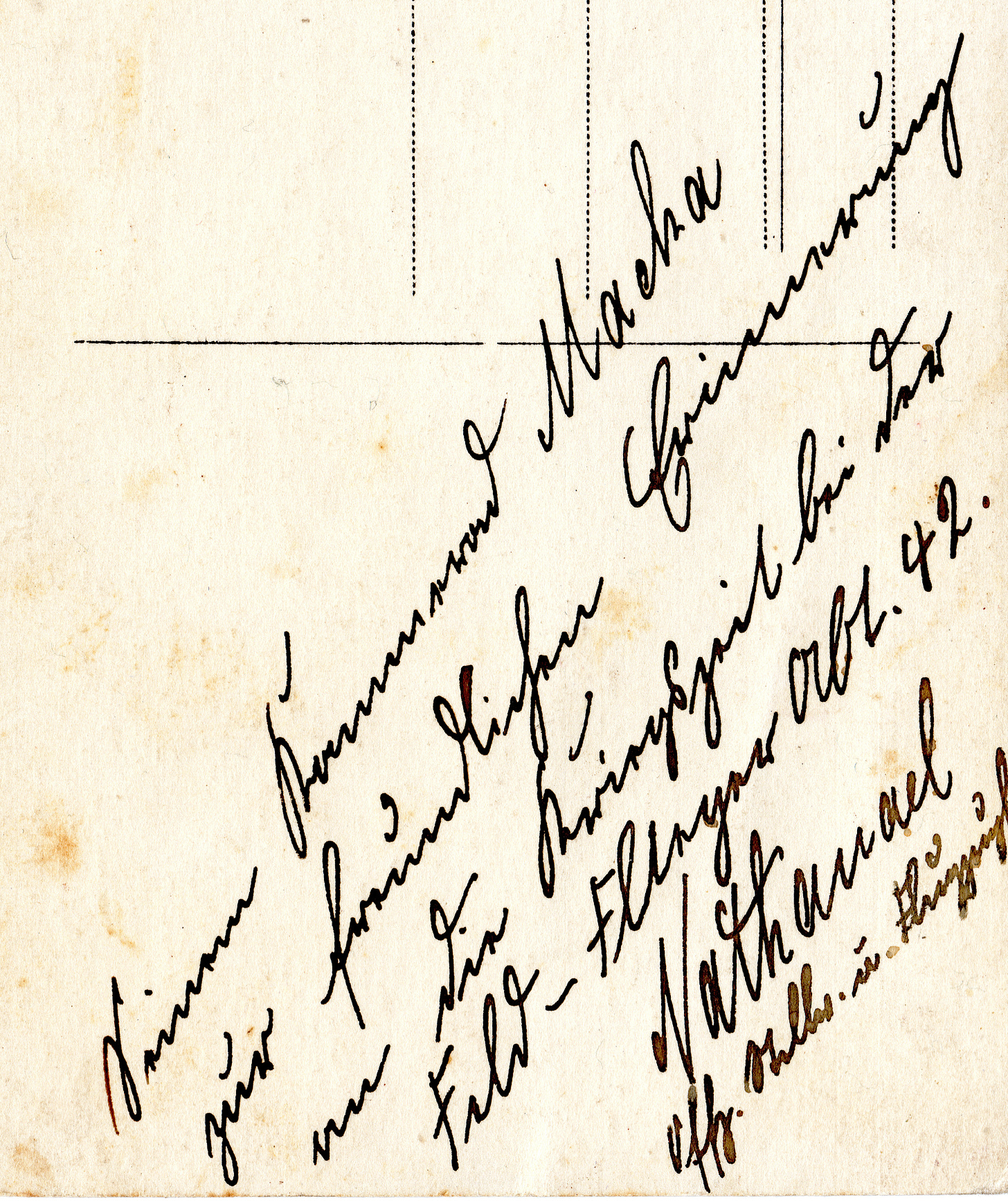

Emil Edmund Nathanael was born on 18 December 1889 in Dielsdorf, a village in what then was the Duchy of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach. Edmund’s father Karl ran a small tailor’s shop and generated enough income to allow his family, his wife Wilhelmine and his four children, two boys and two girls, to live a simple, but secure life. According to Nathanael’s great grand-niece Elise Diethold, who today lives not far from the ancestral home in Vogelsberg, the children all visited the Volksschule after which Edmund’s education was continued at the Wilhelm Ernst Grammar School in Weimar. Edmund and his younger brother August Karl Friedrich were both drafted for compulsory military service before the war. In which unit they served is unclear. Frau Diethold was also kind enough to rummage through two substantial drawers full with family papers which didn’t add much to Edmund’s story, but contained a copy of Sanke postcard No. 537, which shows Edmund Nathanael in front of his Albatros D.III on Jasta 5’s airfield at Boistrancourt in the spring of 1917.

According to Frau Diethold both Nathanael boys served ‘bei den Jägern’; and indeed the casualty lists confirm that August Nathanael was killed serving in Jäger-Bataillon Nr. 4 in October 1914. I see no reason not to believe that his brother Edmund served in the same unit. Very little else is known about his service in the infantry, except for the fact that he was decorated with the Iron Cross 2nd Class before volunteering to join the air service some time in the second half of 1915. In the spring of 1916 we find Edmund Nathanael in France, as a pilot in Feldflieger-Abteilung 42 (FFA 42). When exactly he joined the unit, which until February of that year had been commanded by Hauptmann Hugo Sperrle, the later Fieldmarshall of the Luftwaffe, is unknown. Nathanael soon made a name for himself flying reconnaissance missions deep into enemy territory. One of the earliest mentions of him can be found in the Jenaer Volksblatt on 15 April 1916, which reported about Nathanael’s decoration with the Iron Cross 1st Class.

Dielsdorf: The pilot in the western theatre of war, Offiziers-Stellvertreter Eduard [sic] Nathanael from here, was awarded the Iron Cross 1st Class on the 7th of this month for outstanding and successful reconnaissance flights in enemy territory. Nathanael already holds the Iron Cross 2nd Class and the Weimar General Honour Decoration in Gold with Swords.

On 4 August he was decorated with the Wilhelm Ernst War Cross of the Duchy of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, which was only awarded 366 times (22 times to aviators). Having proven himself as a flyer, Nathanael transferred to fighters in November 1916, joining the newly raised Jagdstaffel 22 (Jasta 22) at Vaux, Laon. The Jagdstaffel stood under command of Oberleutnant Erich Hönmanns, who 24 years later in January 1940, would become involved in the so-called Mechelen incident. Edmund Nathanael didn’t score any victories during his time in Jasta 22, but was nevertheless transferred to another fighter unit, the prestigious Jagdstaffel 5.

JAGDSTAFFEL 5

Like many others of the early Jagdstaffeln, Jasta 5 had originally been a Kampfeinsitzerkommando (KEK Avillers), assemblies of combat single-seaters, Fokker and Pfalz monoplane fighters, formed to combat the concentrations of enemy aircraft in particular sectors of the front. In the case of KEK Avillers, throughout most of 1916, this sector was Verdun. Command of the KEK and later Jasta 5, was Oberleutnant Hans Berr. Jasta 5 was formed on 21 August 1916 at Bechamp near a small village about 8 kilometres east of Etain. About a month later it was moved to the Bellevue Ferme near Senon and on 11 March 1917 to Boistrancourt where it conducted operations in support of 2. Armee. By the time Edmund Nathanael joined the unit, Jasta 5 was one of the most successful and promising fighter units on the Western Front, having scored 37 confirmed victories in the five and a half months since its establishment. With Hans Berr, himself an ace decorated with the Pour le Merite, Jasta 5 had an excellent and influential leader who commanded the respect of his men.

Why Edmund Nathanael, a national of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach and an inconspicuous pilot in the rather unsuccessful Saxon Jagdstaffel 22 was transferred into Hans Berr’s elite formation, becomes explicable when looking at Berr’s activities before entering the flying service. Berr was a career officer who had joined the army in 1908. At the outbreak of war in 1914 he was serving as Adjutant of 3rd Battalion of Jäger-Bataillon Nr. 4. It is highly likely that Berr and Nathanael were already acquainted with one another and that it was Berr who made sure that an old comrade, the former Jäger NCO Nathanael could join him in Jagdstaffel 5. When exactly Nathanael joined Jasta 5 is unknown.

On 6 March 1917 Jasta 5 was involved in a large dogfight over Gueudecourt in which Offiziersstellvertreter Edmund Nathanael claimed a ‘Morane 1’, in fact a Morane-Saulnier P two-seater of No 3 Squadron RFC. The pilot Lieutenant Cuthbert William Short MC managed to land his stricken aircraft in friendly territory but later succumbed to his wounds. Lieutenant Simon MacKay Fraser, Short’s observer, was wounded.

Guided by Berr and supported by a fiercely competitive and highly trained group of comrades, Nathanael had scored his first victory, setting himself on the path of a meteoric career. On 11 March, the first day on Jasta 5’s new airfield at Boistrancourt, Nathanael shot down an FE.2 of No.18 Squadron. The machine went down in flames near Bapaume, killing both occupants, Sgt. H.P. Burgess and 2/Lt. H M Headley. For some obscure reason however, the victory was initially credited to a crew of Schutzstaffel 3 (Schusta 3). It is clear that Nathanael protested against this and the victory was duly credited to him on 17 April. On 20 March, after a long string of unconfirmed victories, Leutnant Renatus Theiller scored his 11th victory, making him Jasta 5s top-scoring ace, a title he should not hold for long. On 24 March the Jasta clashed with several Sopwith 1 ½ Strutters of No. 70 Squadron RFC on a reconnaissance deep behind the German lines. Jasta 5 attacked the British formation over Oisy-le-Verger. In the ensuing fight Nathanael pursued and shot down Strutter A957 over Ecoust-Saint-Mein. The crew, Capt. Lowrey and Lieutenant Swan managed to land their bullet riddled machine, but both succumbed to their wounds. In the same dogfight one of Nathanael’s fellow pilots, Leutnant Heinrich Gontermann, who would end the war with 39 victories and the Pour le Merite, scored his 5th victory. More tragically however, Jasta 5s top-scorer Renatus Theiller, who two days before had scored his 12th victory, had been severely wounded by a bullet which had severed the femoral artery in his thigh. Bleeding severely he had conducted a forced landing, but passed away before help could arrive. In the morning hours of next day Jasta 5 clashed with No. 70 Squadron once again with terrible results for the British formation which within a few minutes lost five aircraft to German fire. Nathanael shot down one Strutter over Velu and only a few minutes later a Nieuport 17 east of Beugny.

In ‘Bloody April’ 1917, Nathanael added a staggering nine victories including two balloons to his tally. Interestingly this avalanche of aerial victories and the fact that he was now the the highest scoring ace of Jasta 5, followed by Kurt Schneider and Heinrich Gontermann, he was not showered with any more decorations, as he was already relatively highly decorated with the Iron Cross First Class and the Wilhelm-Ernst War Cross. On 30 April Nathanael shot down an SE.5 of No. 56 Squadron, the first SE.5 to be lost in combat, killing its pilot Lieutenant Maurice Alfred Kay. On 6 May 1917 a Nieuport 23 of No. 60 Squadron fell to Nathanael’s guns north of Bourlon Wood. Six days later tragedy struck. During a dogfight with SPAD VIIs of No. 24 Squadron over Bourlon Wood in the late evening of 12 May 1917, Nathanael’s Albatros was shot into flames by Captain William Kennedy Cochran-Patrick, an ace who would end the war with 21 aerial victories. Heavily damaged and on fire Nathanael’s Albatros went into a steep, prolonged dive in which the upper wing of the machine ripped off. If Nathanael was killed by Chocrane-Patrick’s fire, by the flames or in the resulting crash south of Bourlon Wood, is not known. Neither do we know if his body was ever recovered and buried - it is likely that he still rests somewhere near the crash site.

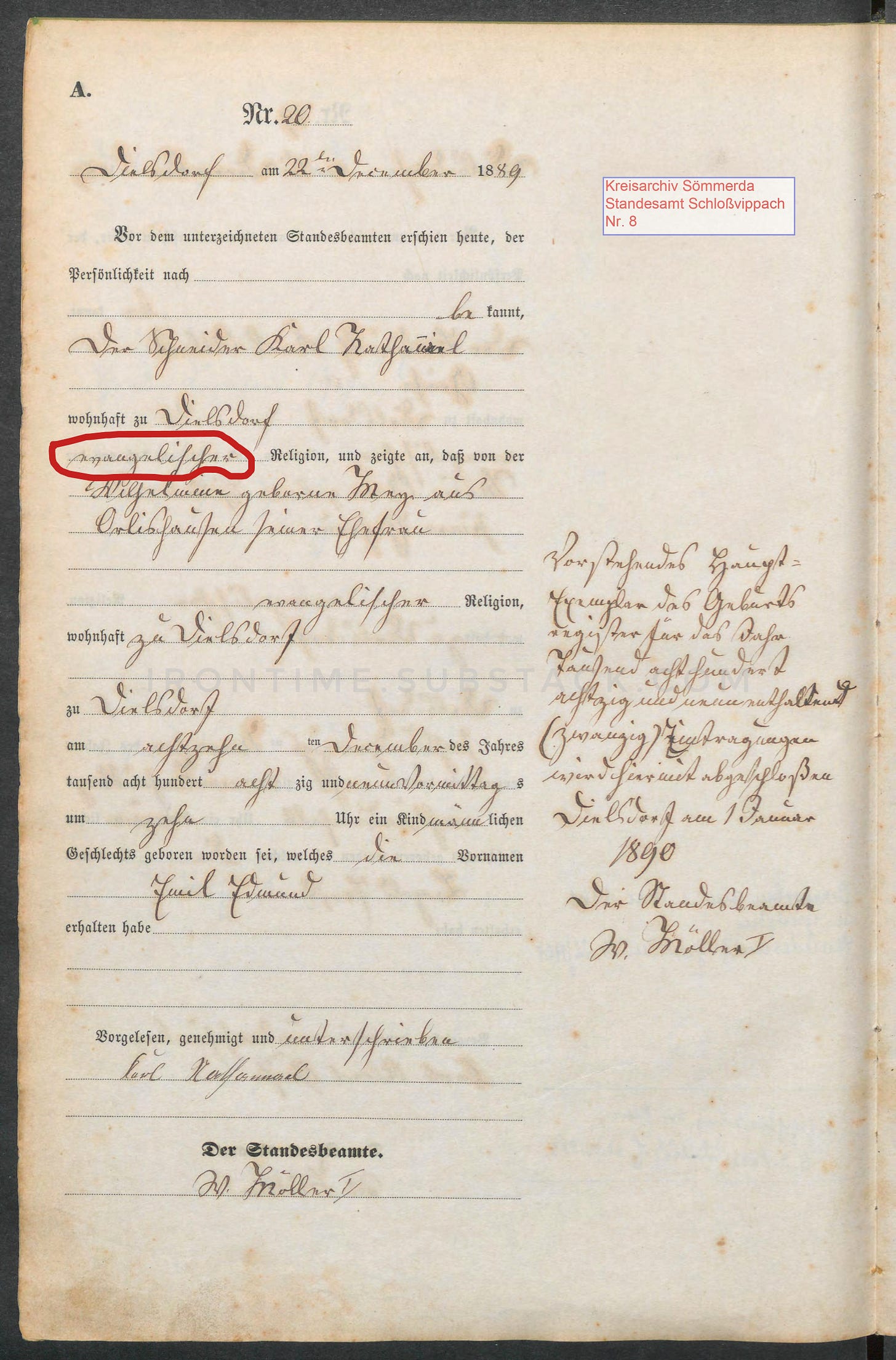

Nathanael’s death certificate, which today is held in the archive’s of the registry office in Schlossvippach, a municipality in the Sömmerda district of Thuringia, reads:

On the basis of the notification from the Royal Prussian Flieger-Ersatz-Abteilung Nr. 7 (Flying Replacement Detachment No. 7), Jagdstaffel 5 dated 23 June 1917, it has been registered today that the Offiziers-Stellvertreter Edmund Emil Nathanael, of protestant religion, last residing in Dielsdorf, born on 18 December 1889 in Dielsdorf, unmarried son of the farmer Karl Nathanael and his wife Wilhelmine, née May, both residing in Dielsdorf, was killed in air combat on 11 May 1917 near Bourlon west of Cambrai.

THE MYTH OF THE JEWISH ACE

Anyone who is acquainted with the name of Edmund Nathanael and German First World War aviation, will have come across the claim that he ranks among the German-Jewish aces of the Great War. From Wikipedia to numerous online articles and specialist forums, in history books and in the press, one can find reference to the fact that Edmund Nathanael was a Jew. I don’t know where this rumour comes from or who has spread it first, but I wonder why no one seems to be questioning it. The above death certificate clearly states that Edmund was ‘evangelisch’, he was a protestant. Of course to access this information one needs to do actual, old school research work (i.e. in an archive and not on the internet), so it is not surprising that this bit of information has been overlooked so far. While I was there, I also took a look at Edmund’s birth certificate, and that of his father, mother and grandparents. Edmund was born protestant, as a child of protestant parents. Today family members and relatives are still protestant. At no time, at least not in the 200 years or so I managed to check, was there any Jewish connection. Agreed the family name most certainly has Hebrew roots, being German variant of the name נְתַנְאֵל (nətanʾēl), which is composed of the root נתן ntn and the theophore element אֵל ʾēl: "God has given", "God has bestowed". But IF there ever was a Jewish ancestor in Edmund Nathanael’s family it must have been centuries ago.

Much of what we today know about German-Jewish combat airmen in the First World War is owed to Dr. Felix Aaron Theilhaber, a Berlin dermatologist. During the First World War he was called up as a field surgeon and used the time to write and to collect material on the deployment of Jewish front-line soldiers and in particular Jewish airmen, a task in which he was supported by the Jewish fighter pilot Jakob Ledermann of Jagdstaffel 13. In 1916 he published his first book ‘Die Juden und der Weltkrieg’ (The Jews and the World War). In 1918 followed ‘Jüdische Flieger im Kriege’ (Jewish Flyers in the War) of which a revised edition was published in 1924 as ‘Jüdische Flieger im Weltkrieg’ (Jewish Flyers in the World War), in which he gave accounts of over one hundred Jewish soldiers who flew for Germany. Edmund Nathanael is not mentioned in any of these books.

THE MYTH OF THE JEWISH FIGHTER PILOT

On 5 June 1917, nearly a month after his death, the Militär-Wochenblatt published the notice that Edmund Nathanael had been decorated with the Member’s Cross of the Royal House Order of Hohenzollern with Swords. During the First World War only 18 awards of this rare and prestigious award for NCOs were made to aviators. At the time of Nathanael’s death it had only been bestowed twice before (OffStv. Fritz Kosmahl, Jasta 26 on 9 January 1917 and to VzFw. Sebastian Festner, Jasta 11, on 23 April 1917). Yet for some reason, Nathanel never made it onto the official roll of recipients published during the Third Reich period. This - according to those who invented this theory - was due to Nathanael’s Jewish faith. There is however absolutely no evidence that any of this is true. In fact respected aviation historian Neal O’Connor correctly assumed that Nathanael’s untimely death suspended the approval process which the Militär-Wochenblatt had already assumed as certain. This chaotic chain of events may have led to the omission in the list published privately nearly 20 years later. There is another persistent myth which may have given birth to the above. In 1938 Walter Zuerl published the book ‘Pour le Merite Flieger’, a popular history of the airmen who had been decorated with the coveted Prussian award. Some have claimed that Leutnant Wilhelm Frankl, who won the Pour le Merite on 16 July 1916, was omitted from Zuerl’s book because had been born a Jew. This however is only half-true, as Frankl is listed in Zuerl’s book (1938 edition), just without any backstory. It is however likely that whoever came up with the idea that Nathanael had been expunged from the list of holders of the Members Cross of the Royal House Order of Hohenzollern, had based this assumption on Zuerl’s handling of Frankl.

Others claim that another effect of Nathanael’s Jewish faith was that his stellar performance wasn’t rewarded with a much deserved promotion to officer. In Prussia the path of a career officer was indeed closed to Jews and while there were numerous Jewish-German reserve officers, a Jewish NCO would have found it much harder to make the step into the officer class. Nathanael’s treatment was indeed unfair and did not get unnoticed at the time. In fact, it was even briefly discussed in the German Reichstag. On 13 June 1918 the member of the Reichstag Dr. Ernst Müller-Meiningen gave a fiery speech to the assembly in which he criticised the army’s tendency to favour One-Year-Volunteers when it came to promotion into the officer class. Every German male was legally obliged to complete a stint of military service lasting between 2 and 3 years. For young men of suitable social class and education there were ways to shorten this service period. Those who had earned a so-called One Year Certificate in a Gymnasium (grammar school) could choose to serve just one year of their compulsory military service in order to avoid delaying their university education or other employment. For this it was required to pass a final examination, the One-Year-Exam, which included tests in German, two foreign languages, geography, history, literature, physics and chemistry. Achieving this the recruit would then join service as a ‘One Year Volunteer’ (Einjährig Freiwilliger), was free to choose the unit he wished to be attached to, but was expected to equip, feed and house himself from his own pocket. In an infantry unit this amounted to between 1750 and 2200 marks - a substantial sum of money, roughly equivalent to the financial outlay required to fund a year at university. Due to their high standards of education and, more importantly, due to coming from affluent families with a certain social standing, One-Year-Volunteers were destined and prioritised for promotion.

In his speech Dr. Ernst Müller-Meiningen criticised the fact that often experienced and battle-hardened NCOs often weren’t even considered for promotion just because they didn’t have the One-Year-Exam, while on the other hand ‘17 and 18 year old boys (...) become officers, just because their father had the money to get them through the One-Year-Volunteer exam.’ He then continued to point out that ‘(...) some took years to become officers, if they got that far at all. I only have to mention the names Festner, Manschott, Nathanael, Ibl - all of them famous pilots - to prove it.’ Not his religion had barred Nathanael from becoming an officer, but his family background as the son of a poor tailor (later farmer), whose family was barely able to afford his grammar school education.

I am not holding my hopes up that this article will change any of the myths which have now become ‘lore’, but maybe it’s a start. Die Hoffnung stirbt zuletzt.

Fascinating article Rob - I see that the current Wiki entry for Nathanael still states that he was Jewish.

A light edit is required perhaps 😀

It’s good to be able to read a well-researched article. Something that I have become accustomed to when reading your work. Thank you!