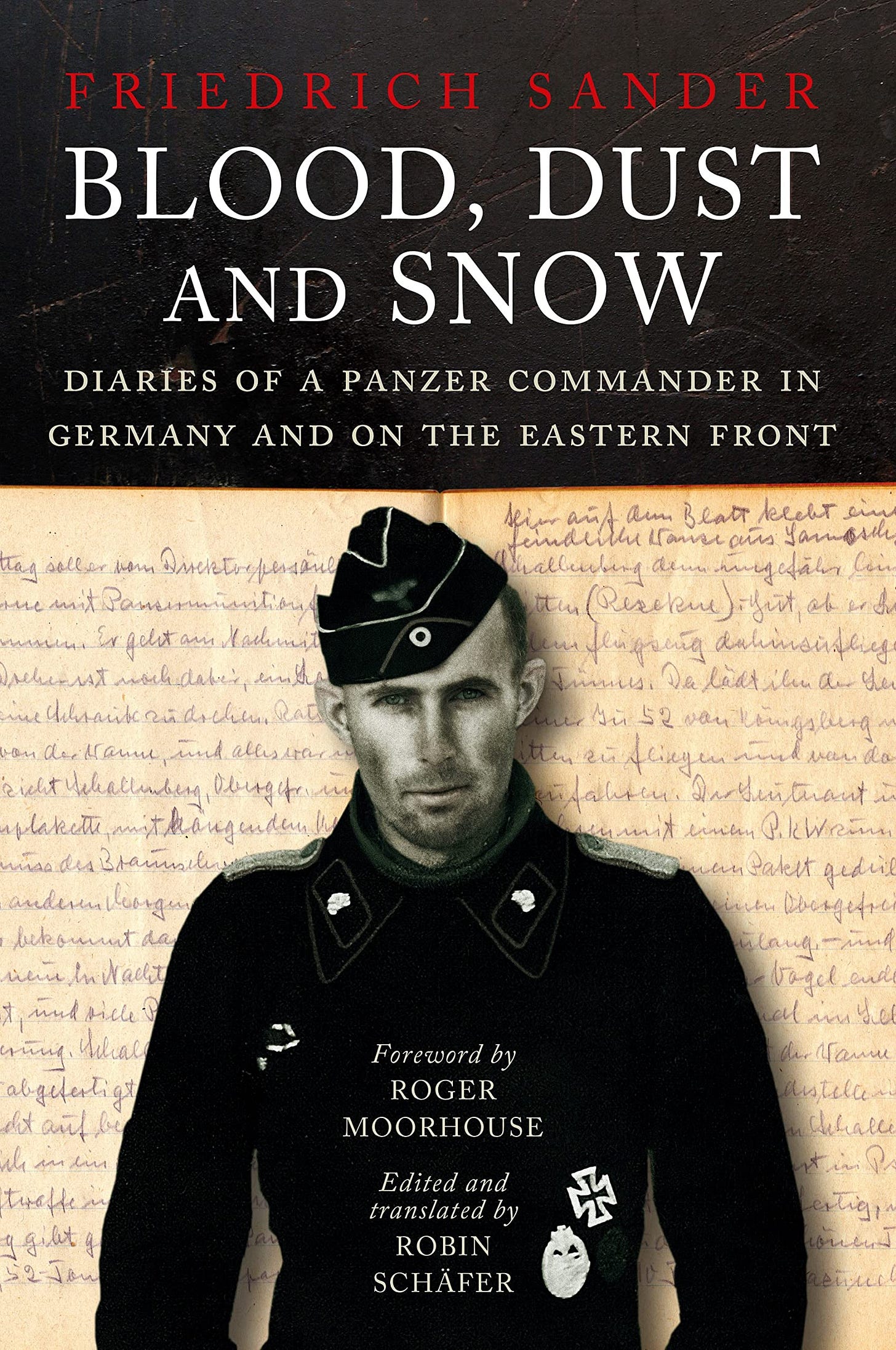

Blood, Dust & Snow: Diaries of a Panzer Commander in Germany and on the Eastern Front

Greenhill Books 2023, ISBN: 1784388300

'An utterly gripping first-hand German account of the war on the Eastern Front.' - Dan Snow

“Unvarnished, absorbing, gritty and pulling no punches. One of the best accounts of war on the Eastern Front I have ever read.” - Peter Caddick-Adams

"An erudite, well-written, thoughtful account of the harsh realities of combat on the Eastern Front in World War Two" - Roger Moorhouse

Editor’s introduction [extract]

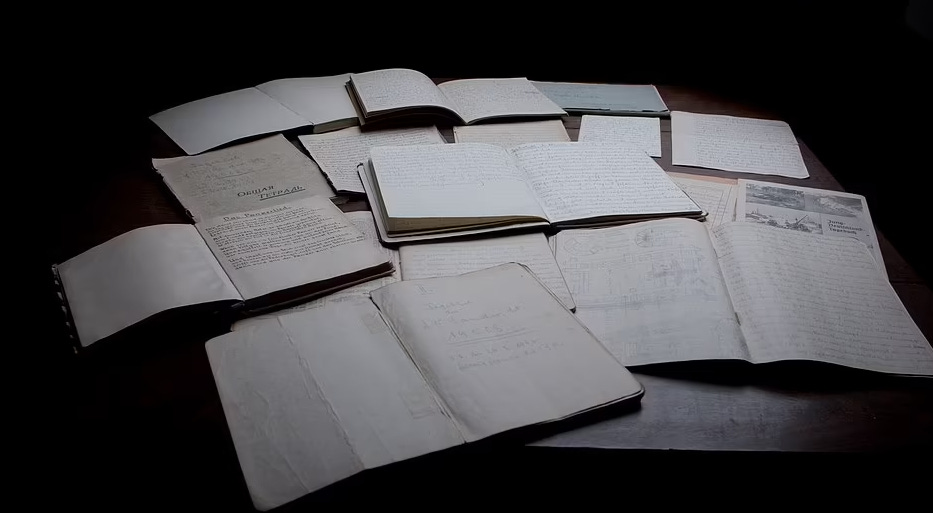

It was the number which first caught my eye, the five-digit number written in blue indelible pencil on the cover of the uppermost of a small pile of worn and frayed notebooks. A German Feldpostnummer, the code which the German military used as identification number for its military mail service. Closer inspection showed that there were 11 books and an accumulation of loose pages unceremoniously held together by a rusty paperclip. After flipping through the pages and looking more closely at the neat handwriting, I knew that I was looking at the wartime diaries of a German officer, Leutnant Friedrich Wilhelm Sander of Panzer-Regiment 11. A brief negotiation with the militaria dealer followed, and a few days later the diaries were lying on my office table.

Upon closer inspection it became clear that the diaries were special; not only was the diarist a keen, even obsessive observer and talented writer, he also thought little of the rules which a campaigning diarist had to follow. There is a persistent rumour that in the German Army the keeping of a diary was strictly prohibited. That is untrue; Keeping a diary peaked in the 20th century and the period of the World Wars. In the numerous social and often associated personal crises, under the impression of sudden, sometimes revolutionary events and brutal wars, and therefore in moments in which the usual conditions abruptly changed, the keeping of a diary or similar journal offered a special and very personal form of coping and served as a remedy against loneliness and despair. In Germany, writing in war, be it in the form of letters or diaries, had a long tradition. Since the end of the First World War, countless diaries were published, which were then replaced in the 1940s by a plethora of völkisch-national war diaries celebrating the war and German feats of arms. Journaling was not only strongly supported by the National Socialists, but was also increasingly used for propaganda purposes. Even the frontline reports of the propaganda sections were often written in the form of diaries, conversely, at the beginning of the war German soldiers were encouraged to keep personal journals. For example, in 1941 the Gauverlag der NSDAP published a pre-fabricated Kriegstagebuch which, according to the advertisement, contained ‘room for photos, a printed war chronicle and a calendar for your own entries. 60 free pages of the best paper and forms for the home addresses of comrades’.

The national-socialist appeal to contribute to a heroic historiography of the Second World War with personal autobiographical memories, caused thousands of German soldiers, who themselves had grown up reading the martial diaries, autobiographies and letters of their fathers and grandfathers, to keep personal journals on campaign. Yet, there were certain rules - written and unwritten - to adhere to, in particular if the diarist was a frontline soldier. It was strictly prohibited to take a diary, or any other personal correspondence, into the furthermost lines where they could potentially fall into enemy hands. It was prohibited to mention names, locations, to write in detail about military matters, to criticise the regime or the military. All this however, clearly was nothing Friedrich Wilhelm Sander was concerned about. Being a Panzermann, he could usually be found in the furthermost line and often far beyond it, deep in enemy held territory. This however didn't stop him from recording his experiences and thoughts in his journal whenever there was time, almost daily, during periods of rest, in quieter moments and even in the turret of his tank during the advance and even very close to the fighting. Neither did he hold back on criticising his comrades, his direct superiors, the general conduct of the war or on critical political commentary. This is even more interesting, because Sander was a National Socialist and a willing tool and crusader for the NS-regime.

Friedrich Sander was born in Graudenz in German West Prussia on the shores of the Vistula River in 1916. When the regulations of the Treaty of Versailles became effective on 23 January 1920 and the city was reincorporated under its Polish name Grudziądz into the reborn Polish state, the Sander family, like most of the city’s German population, chose to leave their home and resettled to Osnabrück in the Province of Hanover. Sander attended the city’s famous Carolinum, Germany’s oldest grammar school, founded by Charlemagne, King of the Franks, in 804 AD. Most likely forced by his family’s financial situation - not unusual during the time - he left the Carolinum early and was apprenticed to a merchant in Osnabrück. As a boy, Sander was a member of the völkisch-national Bündische Jugend, and later - before or after its prohibition and dissolution is unclear - joined the Hitlerjugend. Shortly after his 18th birthday Sander joined the Allgemeine SS and with it the NSDAP. After service in the RAD, he was drafted for compulsory military service on 1 October 1937 and about a month later trained as a radio operator in the newly raised Panzer-Regiment 11 in Paderborn. After further training as tank driver and later tank gunner, Sander was promoted to Gefreiter and set firmly on the path to become a reserve officer in the Wehrmacht, a goal which he achieved in 1939. He took part in the annexation of Sudetenland in October 1938, but not in the German attack on Poland in 1939, during which - much to Sander’s dismay - he served in the regimental replacement battalion. Neither did Sander see action in Germany’s campaign in the west, in the Low Countries and France in 1940, in which he remained garrisoned in Germany.

Eleven of Sander’s diaries survive and it is clear that there was once at least one more, written during his time as an instructor in the Kampfschule [combat school] in Nisch, in Serbia, in 1944, of which a few loose pages survive. It seems however, that he reserved his writing and observational skills for those periods during which he was on campaign, starting with the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. During quiet periods, when on leave at home or during longer ‘peaceful’ spells in occupied France - for instance during the Panzer-Regiment 11’s rehabilitation period in France in the spring of 1942, Sander's voice falls silent. Sander himself tells us that he is writing for a purpose, and the boredom of everyday life, no matter if private or military, seemingly did not befit that purpose. Sander documented the great events that played out before him and his own role within them, but seemingly for no other audience but himself. When at Tretjakova, on 14 January 1942 after receiving ‘a hammering’ by the Red Army, he questions if he should continue to ‘preserve the whole drama’ in his diary ‘for posterity’, as a kind of documentary for some future reader this is clearly just rhetoric. Sander’s diaries are not only awash with critical remarks on his fellow officers, his superiors, on German strategy and tactics, even on Adolf Hitler and ‘Jupp’ Goebbels, they also include drastic descriptions of the violence and suffering experienced by both sides during the campaign, the multitude of German casualties and atrocities conducted by the German Army against Russian prisoners of war and the civilian population. Of course Sander knew that he could never present his writings to a wider audience and his goal wasn’t the documentation of Germany’s struggle against Bolshevism.

Only once, in a new diary which he opens on 15 November 1942, on a train taking him from rural France back to the harsh reality of war on the Eastern Front, he is beginning to write with the intention of some day sharing a ‘description of the sights we see (...) of the fighting we experience and of the tribulations we face’ with his newly-wed wife Ruth. He does however quickly revert to his usual way of writing and continues to do so only for himself and for the cathartic experience of putting pen to paper. ‘Finding the words to describe what I have experienced during that time - is that even possible? I don’t know, but I will try - even if it's just to give myself some clarity and to unburden my mind’, he writes on 28 December 1942. In stark contrast to the vast majority of German soldier’s memoirs, autobiographies and diaries published after the end of war Sander’s diaries are not agenda driven, they were not written or edited to fit a political and social Zeitgeist and to appeal to the tastes of a certain kind of audience. Sander’s diaries offer a totally genuine and honest glimpse into the mind and world of a highly-politicised, young officer of the German Panzerwaffe during the first half of the Second World War and as such they are totally unique.