BLOOD ON THE STREETS

The 'Spartacist Uprising' and the first Battle of Berlin by Dr. Immanuel Voigt

RED IS THE SUN

It was a mild but rainy November morning, but the precipitation didn't stop anyone from rushing to the streets and squares in large numbers. That the war, which had been dragging on for over 4 years, had to be ended immediately, that was the popular opinion. For too long, the people had witnessed the weak efforts of the government and the heads of state, they were tired of repetitive slogans about striking a ‘final and decisive blow’. The war weariness of the German people was evident and news were coming in thick and fast. Barely an hour passed without the next ‘breaking news’ being announced on the broadsheets. Even the newspapers found it difficult to keep pace.

On 4 November 1918, after Admiral von Hipper had ordered the entire High Seas Fleet to sally out for a to fight a final ‘honourable’ battle with the English and Americans in the Southern Bight. Discontent had long been smouldering among the crews of the German High Seas Fleet. The sailors, with the longed-for end of the war just around the corner, did not intend to risk their lives, neither in a great naval battle, nor in a last-minute mutiny. But when they were given the choice of putting their lives on the line once again, the crews of several large vessels decided in favour of mutiny. In Wilhelmshaven and Kiel the men rebelled and dramatic scenes unfolded. On 29 October 1918, the crew of the battleship SMS Thüringen refused to follow order and sabotaged parts of their ship, an affront which the officers of the ship could not accept. As a result, torpedo boats B110 and B112, and the U-135, were called to the Thüringen, turning torpedo tubes and guns against the ship, while the mutinous crew were given an ultimatum to surrender. Shortly afterwards, SMS Helgoland was brought about and turned its medium artillery on the torpedo boats and submarine. After anxious minutes of dramatic tension, the crew of the Thüringen surrendered.

That day, 314 sailors and 124 stokers, including those from SMS Helgoland, were arrested. The uprising, however, could not be stopped. Due to uncertainty caused by the mutinies, von Hipper and the head of Naval War Command, Admiral Reinhard Scheer, cancelled the scheduled offensive operation, which resulted in Wilhelm IIs famous statement: ‘I no longer have a Navy’. He could not have known how more difficult the coming days would become for him. Meanwhile, the first workers and soldiers council was formed in Kiel, and took control of the city.

Also on 4 November, the Villa Giusti Armistice brought an end to hostilities between Austria-Hungary and Italy, albeit that Austria-Hungary had not agreed this with its German ally. On 5 November, American President Woodrow Wilson was finally willing to start peace negotiations. Meanwhile, sailors in Kiel called for a general strike. By then, the maelstrom was picking up a breakneck speed and more and more German cities were sucked into the revolutionary maelstrom as the call of the people to end the war rang ever louder.

The first bombshell dropped in Munich: After he had spoken to 60,000 people on the Theresienwiese, Kurt Eisner and his revolutionary government proclaimed the ‘Free People's State of Bavaria’. The Bavarian King, Ludwig III, fled hastily from Munich. In Berlin, people on the streets went one step further, openly demanding the Emperor's abdication. The SPD faction threatened to leave the government if Wilhelm II did not act by the next day. On 12 November the Bavarian King Ludwig III released his soldiers and civil service officials from their oath, thus ending the 738-year rule of the House of Wittelsbach in Bavaria.

SPIRALLING OUT OF CONTROL

In the meantime, the Entente powers, under Marshal Ferdinand Foch, met the German delegation under the chairmanship of the centre politician and parliamentary state secretary, Matthias Erzberger, in the forest of Compiègne to negotiate the armistice while Chancellor Max von Baden unsuccessfully tried to persuade Kaiser Wilhelm II to abdicate. Rather, Wilhelm fantasised about ‘restoring order in the homeland at the head of the Army’ together with the OHL (German Supreme Army Command). But in view of revolutionary events in the Reich, this was completely illusory.

On 9 November, events were spiralling out of control when the revolution finally reached Berlin. Chancellor Max von Baden announced the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II without further consultation, handing over his office to SPD politician Friedrich Ebert - even though he was not entitled to under the constitution. Shortly afterwards, Ebert's party comrade, Philipp Scheidemann, stepped onto a balcony of the Reichstag and spoke to Berliners gathered in large numbers: ‘Workers and soldiers’ he stated ‘...the Emperor has abdicated; he and his friends have disappeared’. The ‘old and rotten’, the monarchy, had collapsed. Now there lived ‘the new’: the German Republic

A few hours later, Spartacist Karl Liebknecht proclaimed the ‘Free Socialist Republic of Germany’ in front of the Berlin City Palace, calling out to the people from the roof of a car that ‘the day of revolution’ had now come. Meanwhile, on that day, large crowds moved through the centre of the German capital.

‘On the embankment, endless trains of soldiers with rifles at their backs, wearing their hats lopsided and red ribbons in their buttonholes, so they look completely different, and workers, some with guns, in between big red flags. In front and to the side were marshals with guns and red armbands. Large trucks, taken from military depots, on which soldiers and civilians perched with guns, rolled through them.’ - Theodor Wolf, Editor-in-Chief of the ‘Berliner Tageblatt’

This is the reality now. One experiences it and doesn't quite get it. The columns of workers that crossed the city in the morning carried signs...that read: ' Brothers! Do not shoot!' - but there is supposed to have been shooting at the War Ministry.’ - Käthe Kollwitz, German artist

There were occasional shootings. On the evening of 9 November, Wilhelm II, now demoted to ex-Emperor, fled his HQ at Spa, Belgium, and into exile in Holland; bourgeois and conservative circles in Germany could hardly believe what was happening before their eyes. Practically overnight, the old order was swept aside, the monarchy eliminated without compromise. There hadn't even been negotiations!

For diplomat Harry Graf Kessler, it was the ‘...most memorable and most terrible day in German history’. He was particularly shocked by the Emperor's abdication: 'This kind of end of the House of Hohenzollern; so pathetic, so incidental, not even in the focal point of events.’

‘TERRORIST BOLSHEVISM’

After the double proclamation of a Republic, three groups struggled for power: on the one hand, old state elites, who, with the majority of the army and administration, were not ready to accept or acknowledge the new status quo. Opposite them stood the Reichstag majority, composed of moderate Social Democrats, the centre and the left-wing liberals. Above all, they wanted to establish a modern, democratic state that left existing economic and social structures untouched. Thirdly there were radical left groups which openly rejected parliamentarism, such as the Spartakusbund under Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. The latter modelled itself on the principles of the Russian October Revolution of 1917, aiming to establish a Socialist Soviet Republic.

The power vacuum lasted only one day however, because on 10 November the majority of Social Democrats (SPD) and Independent Social Democrats (USPD) agreed equal cooperation in a ‘Council of People's Representatives’. This council comprised three men from each party, chaired by Friedrich Ebert (SPD) and Hugo Haase (USPD). This transitional government would exist until a new government had been created through legitimate and free elections. On the same day, the army sided with the new government.

General Wilhelm Groener, who after Erich Ludendorff's dismissal, was the new First Quartermaster General, led the fate of the OHL1, and together with Feldmarschall Paul von Hindenburg, expressed the loyalty of the military to Ebert, assuring him the Republic would be protected against the spread of ‘terrorist Bolshevism’. In return, Ebert guaranteed him full sovereignty. A secret telephone line was then set up between the Reichstag and the OHL. This would later be of great importance.

In any case, the new government wanted to prevent a bloody civil war and the agitation of radical left groups. With the military, the ‘Council of People's Representatives’ gained decisive power, since it now had an instrument to assert its interests with force. At the same time, enemies of the republic and monarchists simply continued to serve in the ranks of the army, openly rejecting the new government. However, there was no real alternative for Ebert and his party comrades other than to rely on parts of the old army and, a little later on, the Freikorps2. Or, as historian Rüdiger Bergien aptly put it: ‘After 9 November 1918, in the short space of time, Ebert could not have set up a new, and above all, a purely republican military system. ’ On 11 November 1918, the centre politician Matthias Erzberger finally signed the infamous armistice treaty in Compiègne. A good three years later, he was murdered by two members of the right-wing national ‘Organisation Consul’; one of the reasons for his murder: the signing of the armistice.

The new government, meanwhile, paved the way to a free democratic constitutional state and with a declaration on 12 November, unrestricted rights of association and assembly were granted, censorship was lifted and the right to freedom of expression emphasised - as was freedom to practice religion. The eight hour working day was also promised to be a reality by 1 January 1919, this always had been a core demand of the Social Democrats.

The situation in Berlin and remainder of Germany remained largely calm until the end of November, with diplomat Harry Graf Kessler noting on 14 November:

‘Today at one, when I was walking down the Linden, the palace guard came from the Brandenburg Gate with the Hohenfriedberger March, just like before, only with red revolutionary flags, the men without cockades and the NCOs or stewards with large greater German black, red and yellow brassards. They marched a little more casually than the guards before the war, but in good order and quite soldierly. A large crowd with red bows and armbands accompanied them.’

During this time, numerous new parties were founded, such as the ‘German Democratic Party’ (DDP), the national liberal ‘German People's Party’ (DVP) and the right-wing conservative ‘German National People's Party’ (DNVP).

FREIKORPS

Nevertheless, there was a lingering tension in the air as the new government expected radical leftists, above all the Spartakusbund, to implement a coup. The group had been founded after the beginning of the First World War in August 1914 as the ‘International Group’ within the SPD. The war, and granting of war credits by the SPD, were criticised and rejected. From 1916, they named themselves the Spartakusgruppe and in 1917, after a split in the Social Democrats, joined the USPD as their left wing. Finally, the Spartakusbund was re-established during the revolution in November 1918 as a Germany-wide non-party organisation. The propagated goal was the creation of an all-German Soviet republic. The supporters of the covenant were called Spartacists.

It quickly became apparent that the radical left, which the Spartacists wanted to enforce with armed force if necessary, was barely capable of attracting a majority across the Empire. Nevertheless, the organisation, especially Karl Liebknecht, was perceived as a threat - especially during the days of the revolution - that might appear at any time and cause unrest. Friedrich Ebert and his party comrades therefore counted on the Freikorps, which had been raised all over Germany and beyond since the end of November 1918 to take over protection of the young Republic if required.

The Freikorps were voluntary associations, mostly founded under the leadership of prominent officers or highly decorated war heroes, often bearing their names. Most men in the Freikorps were former soldiers who had returned home from the front, and sometimes students or schoolchildren. Last, but not least, and this was to become a problem by 1920, most Freikorps troops were monarchists and openly rejected the Republic. Historians such as Heinrich August Winkler and Joachim Käppner saw the greatest mistake of the transitional government in Friedrich Ebert lining himself with the OHL, instead of exercising control over the troops through the War Ministry.

By the spring of 1919, the Freikorps had become a considerable military power. By then, over 120 such groups had been raised, with a combined strength of 200,000 to 250,000 men. Some were equipped with heavy weapons such as artillery, mortars, machine guns, aircraft and even tanks.

BLOOD ON THE STREETS

Nobody had suspected that Friday 6 December 1918, would end with a bloodbath. And yet events that day would lead to considerable tension between the ‘Council of People's Representatives’ and the radical left. At the same time, the day gave a foretaste of the bloody struggle for power that would turn Berlin into a battlefield.

Shortly before 6 p.m, several columns of armed workers and soldiers marched to the Reichstag where a navy Feldwebel Spiro of the Volks-Marine-Division spoke to the assembled crowd. In his address, he called for the election to the National Assembly to be brought forward to 20 December. In addition, he quickly proclaimed Friedrich Ebert ‘President of Germany’ and then celebrated the ‘German Socialist Republic’.

The group tried to gain access to the Reichstag, repeatedly calling for Friedrich Ebert to appear on the street but when he stepped out, Ebert told Spiro and his men that he would not comply with the demands. At about the same time, 25 armed men, who were also aligned to Spiro, entered the Prussian state parliament to arrest the local politicians. Nothing else but a coup was to take place that evening. But it failed, not only because Ebert rejected the whole thing, and Spiro and his men accepted this without further ado, but also because the arrest of the members of the Prussian state parliament failed. In any case, rumours about the coup d'état soon spread in Berlin and three smaller protests of Spartacists formed in the north of the city.

Worried about the turn of events, the city commandant of Berlin, Social Democrat Otto Wels, ordered 60 soldiers to the intersection of Chausseestrasse and Invalidenstrasse, in the immediate vicinity of the Maikäferkaserne [cockchafer barracks]3, i.e. the barracks of the Garde-Füsilier-Regiment. Here, soldiers blocked the road, positioned a machine gun and established a position. This ensured that hundreds of onlookers gathered, waiting to see what would happen next. What did happen has never been fully clarified, because suddenly the machine gun started firing. Chaotic scenes played out as bullets hit a tram that was just passing, the passengers rushing out in panic. Other people waiting for the tram, jumped through shop windows to avoid the firing, while all around them people collapsed in the hail of bullets. Eyewitnesses stated that when the ‘tack tack tack’ finally stopped, a moment of silence followed. This was broken by the moans and screams of the wounded. Ambulances were hastily called to take the seriously injured to hospitals. The outcome was devastating. At least 16 people died, including several women. The youngest was a 16-year-old girl, fatally shot on the tram. A further 80 were injured, at least 12 seriously. Exactly who was responsible for this bloodshed remains unclear. In the end, both sides blamed the other. Social Democrats, Liberals and Conservatives claimed the Spartacists had been the aggressors and that the soldiers had just responded.

Meanwhile, Karl Liebknecht wrote in the Spartacist newspaper, Die Rote Fahne, that the shooting was deliberately brought about. Historian Mark Jones concludes that the machine gunner acted out of panic. But in the heated mood of the winter of 1918/19, for the ‘newspaper battle’ and thus the right to interpret the event, this was irrelevant. Anti-Spartacist newspapers clearly saw the blame laying with the radical left and the political climate became even harsher. There were increasing calls for violent action against Spartacist leaders, and even the execution and death of Karl Liebknecht. But the street fighting which had initially been expected, did not materialise.

On 10 December 1918, regular troops - mostly from guard formations and in divisional strength - returned to the city. At the Pariser Platz, Ebert welcomed the men with the words: ‘No enemy has ever conquered you! Germany's unity is now in your hands’. During the parades, tens of thousands lined the streets and cheered for the homecoming guardsmen. There were no disruptions or incidents.

Just under a week later, between 16 and 21 December, 514 representatives of all German ‘workers and soldiers councils’ met in Berlin for the ‘Reich Congress of Workers and Soldiers Councils’. These had a joint objective and, above all, advised on the new form of government. Since a good two thirds of the 514 men belonged to the SPD, the decision was made in favor of parliamentary democracy. This paved the way for a new constitution and an election to the National Assembly was scheduled for 19 January 1919. A Soviet-style republic, on the other hand, was rejected by an overwhelming majority. This fueled the anger of the Spartacists and some USPD men in particular. Tensions were increasing by the minute.

BLOODY CHRISTMAS

The fact that these tensions reached their first bloody climax at Christmas is the irony of history. The actual reason for the clashes was offered by the Volks-Marine-Division, the People's Naval Division, an armed formation composed predominantly of revolutionary sailors and formed at the beginning of the revolution. The 1,700 strong unit had been quartered in the Berlin City Palace and the Marstall [New Stables] since mid-November 1918 in some squalor. In any case, a report by the Prussian Ministry of Finance of 12 December speaks of extensive looting there. Therefore, the Berlin city commandant, Otto Wels, asked the leader of the Volks-Marine-Division, Heinrich Dorrenbach, to vacate the palace and reduce his troops to 600 men. In order to put the necessary pressure on Dorrenbach, Wels initially withheld the wages of the sailors. Unsurprisingly, they were not very enthusiastic about this move. On 21 December, the government, i.e. the ‘Council of People's Representatives’, interfered and instructed Wels to pay the 80,000 Marks due, but only after the palace had been cleared. Meanwhile however, the sailors had begun to lose patience.

On 23 December, the ‘Christmas Crisis’ began when armed sailors broke into the Reichstag, blocked all exits, cut the switchboard and put the MPs present under de facto house arrest. At the same time, a larger element of the Division under Dorrenbach tried to penetrate the city command. First, there was a shootout in which two sailors were killed. The building was then stormed and Otto Wels and his employees were arrested. Friedrich Ebert and his party comrades were now in a tight spot, finding themselves in the disadvantageous situation of initially not having any loyal troops available to take action against the revolting sailors.

When Ebert, Philipp Scheidemann and Otto Landsberg, the leading figures in the transitional government, were told on the night of 24 December that sailors had mistreated Otto Wels and threatened his life, they acted. Acting on the report, Prussian War Minister, Heinrich Scheuch, was instructed to solve things via the secret telephone line to the OHL. How far the actual order went, however, was disputed later. Ebert insisted that he only did what was necessary, which was to free Wels, while Heinrich Scheuch said he had also received the order to: ‘...remove the sailors from the palace and Marstall’.

For its part, the OHL saw the time had come to present itself as protector of the German Republic and domestic political order. The action was to be carried out by Generalkommando Lequis, a force set up during the first days of the Revolution under General of the Infantry, Arnold Lequis, and the Garde-Kavallerie-Schützen-Division. In the early morning of 24 December, 1200 men with machine guns and artillery were ready to storm the palace. Shortly afterwards, the order to attack was given. The first shell struck the facade of the palace with a deafening crash. Well over 60 more followed before the infantry advanced to the assault. Government troops managed to capture the palace and Otto Wels was freed, arriving at the Reich Chancellery a short time later. Philipp Scheidemann described the condition of Wels: ‘The face was grey and wrinkled, the eyes that had seen death were hollow. Apparently, he could hardly stand.’

A little later, the tide turned when the Sicherheitswehr of Berlin Police President, Emil Eichhorn (USPD), along with armed workers and even thousands of unarmed women and children, rushed to the palace in support of the sailors, bringing it back under their control. Friedrich Ebert was forced to stop fighting at noon on Christmas Eve. Afterwards, the battlefield was visited by thousands of people, everything, or so it seemed, was waiting for the events that followed. The observations of diplomat Harry Graf Kessler seem almost grotesque:

‘During these bloody events, the Christmas market goes unconcerned: organ grinders are playing in Friedrichstrasse, the jewellers on Unter den Linden are open without a care, their shop windows sparkle and are brightly lit. Christmas trees are certainly burning in thousands of houses, and children play around them with presents from dad, mom and dear aunt. The dead are lying next to them in the stables, and the wounds to the palace and German state have been freshly made during the Christmas season. ’

Meanwhile, the transitional government had no choice but to negotiate with the Volks-Marine-Division. This was an admission of blatant defeat, not only on a political but also a military level. Eleven sailors and 56 guardsmen were killed in the fighting. The political discourse between moderate forces and the radical left was finally over. As a result of this ‘Christmas Crisis’, the USPD men Hugo Haase, Wilhelm Dittmann and Emil Barth left the transitional government on 29 December. The vacancies were taken by SPD men Rudolf Wissell, responsible for social and economic policy, and Gustav Noske, who took over the Army and Navy. Noske made it clear that the restoration of public order by all means, including the use of the military, was his declared aim. According to historian Wolfram Wetter, this pre-programmed civil war.

SEETHING CAULDRON

Between 30 December 1918 and 1 January 1919, the Reich Conference of the Spartakusbund took place in the ballroom of the Prussian House of Representatives, later referred to as the founding party congress of the ‘Communist Party of Germany’ (KPD). When it became clear that the Spartacists would have no future within the USPD, the step to found their own party was a logical consequence. During those three days, a majority decided that the KPD would not take part in the elections to the National Assembly on 19 January 1919. The party leadership, and above all Rosa Luxemburg, were against the proposal, but in the end bowed to the majority.

The calm in the capital lasted only a short time. By the first days of January 1919, a new conflict was brewing. The external reason was the dismissal of the Berlin Police President, Emil Eichhorn (USPD), on 4 January, by the Prussian Interior Minister, Paul Hirsch (SPD). The fact that Eichhorn's security forces had taken sides with the Volks-Marine-Division during the Christmas battle for the Berlin City Palace, had brought the police chief into disrepute. The dismissal again called the USPD and KPD on the scene, both parties calling for a protest against Eichhorn's dismissal the following day, a Sunday.

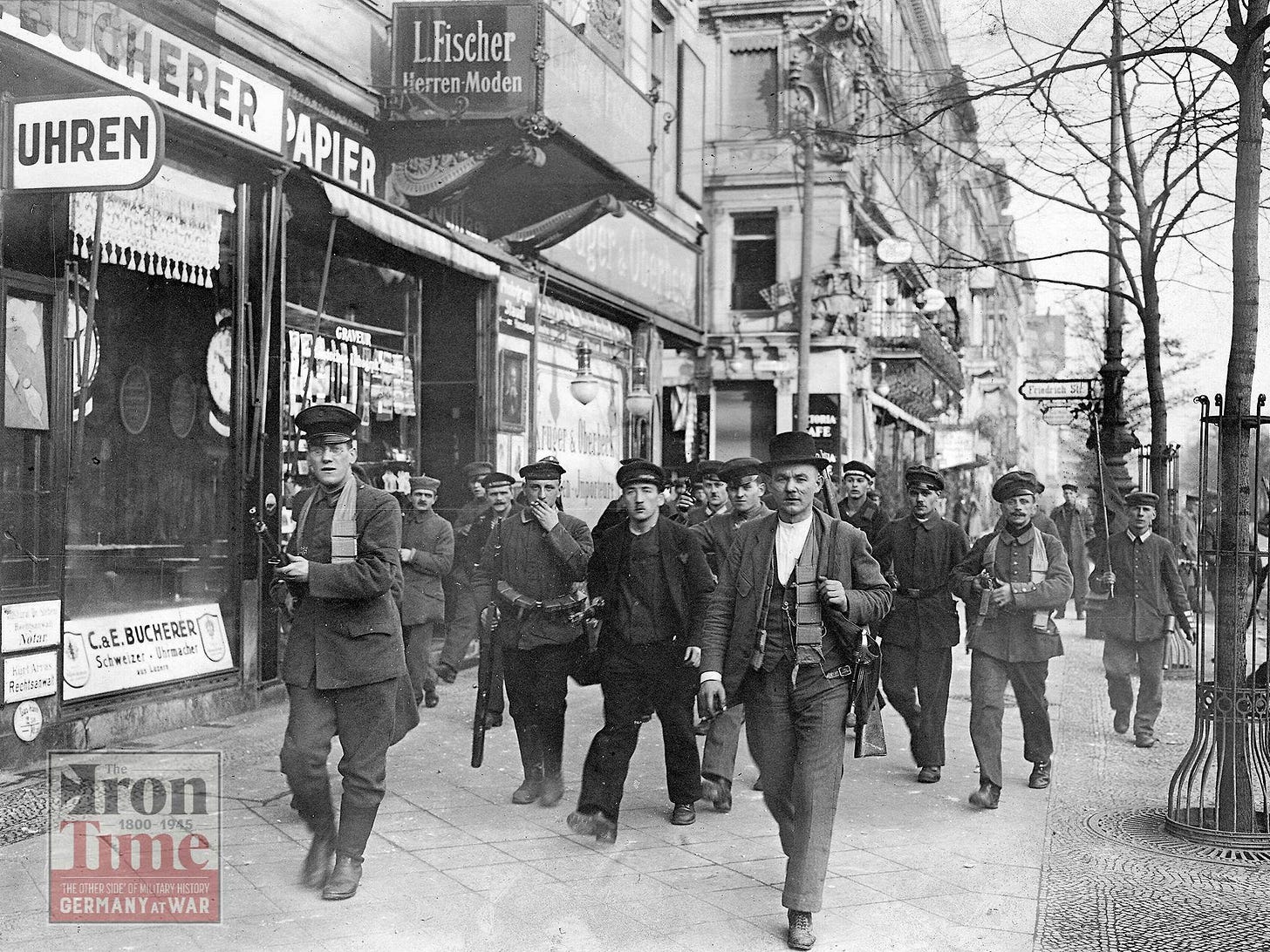

On 5 January, much to everyone's surprise, around 100,000 people marched to the Police HQ on Alexanderplatz, expressing solidarity with Eichhorn. In the course of that day, the situation got out of hand. Armed workers began to occupy train stations and forced their way into the press offices of Büxenstein, Mosse, Scherl and Ullstein and also occupied Wolff's telegraph office. The editorial offices of the social democratic newspaper, Vorwärts, were equally occupied.

On the evening of that day, 90 supporters of the radical left came together to form a ‘revolutionary committee’ and decided to call a general strike the following day, declaring the social democratic transitional government dismissed. It must be noted, however, that the majority of demonstrators did not take part in the occupations, but went home at the end of the day. Only a small radical group, to which Karl Liebknecht belonged, planned the overthrow.

On 6 January, even more people were out on the streets of Berlin, because the interim government had called on them to protest against the acts of violence of the ‘Spartacus gang’. Harry Graf Kessler's writings of this event is extremely dramatic, although the really bloody days were still to come:

‘All of Berlin is a seething cauldron in which violence and ideas whirl together. Indeed, it is a matter of world history; not only about the continued existence of the German Reich or the democratic-republican state, but about the decision between West and East, between war and peace, between intoxicating utopia and grey everyday life. Never since the days of street fighting during the French Revolution has so much been at stake for mankind.’

But, for now, all remained calm. Meanwhile, insurgents tried to pull the Volks-Marine-Division on their side, but did not succeed. Another day passed, and Karl Liebknecht and his entourage set up their headquarters in the Bötzow brewery in Berlin's Prenzlauer Berg district. The party leadership of the USPD and Emil Eichhorn were, to put it mildly, irritated by the insurgents going it alone, seeing neither any chance of success for the action and being unable to approach Liebknecht because any attempt at contact was blocked. Curt Geyer (USPD), a member of the Leipzig Workers and Soldiers Council, finally managed to meet Liebknecht in the Bötzow brewery, the Spartacist looking to him as if he was overwhelmed by the whole situation that he himself had helped cause. Geyer ‘doubted his sanity’, because Liebknecht himself seemed to have understood that in the upcoming fighting he probably had no chance against troops loyal to the government. But that was the salient point: if there had been any chance of success for the overthrow of the radical left, then it could only be with the support of troops present in Berlin. However, like the Volks-Marine-Division, these could not be drawn to the rebels’ side.

HOUR OF RECKONING

In the meantime the transitional government prepared to counterattack, determined to accept the challenge. Gustav Noske now followed his announcement to restore public order by saying: ‘One has to become the bloodhound, but I am not afraid of the responsibility!’

Noske pulled together the Freikorps around Berlin from his Dahlem HQ. Meanwhile, the USPD tried to prevent bloodshed by forming a mediation committee. But the government's SPD men made it clear that negotiations would only take place when freedom of the press was fully restored, i.e. when the occupied publishing houses were evacuated. This, in turn, was refused by the insurgents. Thus, the inevitable followed. On 8 January 1919, the transitional government issued an appeal to Berliners: ‘Violence can only be fought with force. The hour of reckoning is approaching!’

In the early morning of 11 January, the assault on the Vorwärts publishing house on Lindenstrasse began. The Freikorps Regiment Potsdam, under Major Franz von Stephani, was entrusted with the task. The first 10.5 cm shell hit the building at around 8 a.m and others followed. After the artillery preparation, the actual assault was conducted by infantry in the manner of a classic stormtroop operation. But the defenders of Vorwärts shot well and inflicted heavy casualties on the Freikorps despite their inferiority. A well-positioned rebel machine gun caused much anger among the attackers, being responsible for many losses in their ranks. Later, a false rumor circulated that Rosa Luxemburg had operated this machine gun herself. The assault had not gone according to plan, but in the end the superior force of the attackers was too great. After another heavy artillery bombardment had severely damaged the building, and at around 10 o'clock, five unarmed men came out to negotiate. The anger of the Freikorps, however, was so great that the men were immediately captured and taken to the nearby Garde-Dragoner Karserne [Guard Dragoon barracks], joining two couriers which had already been captured. Around 10.45 a.m., the last shots died away in Lindenstrasse. and the occupiers of Vorwärts gave up. The government soldiers had been victorious.

GUARD DRAGOON BARRACKS MASSACRE

In the Guard Dragoon barracks, pent-up anger over casualties taken while storming Vorwärts was now directed at the captured insurgents. Members of the Regiment Potsdam, as well as young officer cadets of the Garde-Dragoner, all loyal to the government, took the call for reckoning literally. After severe physical abuse, the prisoners were put against a wall and shot, in some cases several times. Some corpses were badly disfigured as a result. How great the soldiers' anger could be, even against their own men was demonstrated when an officer of the government troops was beaten up by his own men because he had thanked the insurgents for his good treatment with a handshake. He had previously been held hostage in the Vorwärts building. All 200 to 300 insurgents who had given up were also taken to the Guard Dragoons barracks. On the short walk to the barracks, not only did civilians abuse the prisoners, but they were also beaten and kicked by soldiers. One officer threatened: ‘Your arse will be ripped open up to your collar’.

When the barracks were reached, the soldiers' anger began to turn against the 15 to 20 women among the prisoners. One was Frau Hilde Steinbrink, who had cared for the wounded in the cellar of the Vorwärts. Since the government soldiers still suspected Rosa Luxemburg was among the rebels, but could not find her, they began to attack Hilde Steinbrink instead. She was initially insulted as ‘Red Rosa’, slapped in the face, kicked and beaten with rifle butts. Then she had to stand in front of a wall as several soldiers aimed rifles at her. But there was no shooting. Rather, they told her: ‘See! Powder is too good for you. We will tear you open and divide you up so that everyone has a piece of you.’ However Major Franz von Stephani stepped in and saved the life of the young woman before things escalated further. One reason being that Wilhelm Stampfer, an editor of Vorwärts, was present and Stephani did not want the embarrassment of such arbitrary justice. Nevertheless, the scandal remained that seven prisoners had executed without judgement.

On 12 January, the other occupied press houses were evacuated by the insurgents. The ‘January uprising’, which historian Volker Ullrich described as having been ‘...begun in an amateurish way and carried out half-heartedly’, ended after a week. A total of 165 people, soldiers, insurgents and civilians, had been killed.

ROSA AND KARL MURDERED

At the beginning of the revolution, the leaders of the radical left, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, were exposed to open hostility. The situation worsened after the end of the ‘January Uprising’, with many blaming Luxemburg and Liebknecht for the escalation of violence. Both could no longer dare to appear in public and hid in the apartment of friends in the Berlin district of Wilmersdorf. From here, on 13 January 1919, they wrote the last articles for Die Rote Fahne newspaper. Luxemburg was combative in her article:

‘You blunt minions! Your order is built on sand. Tomorrow the revolution will rise again with a rattle and proclaim to your horror with the sound of a trumpet: I was. I will be!’

This prophecy was not to come true, and two days later the members of Wilmersdorfer Citizen Defence discovered the hiding place of Luxemburg and Liebknecht. Both were arrested and arrived at the Eden Hotel late in the evening of 15 January. At that time, the Garde-Kavallerie-Schützen-Division, under Hauptmann Waldemar Pabst, was quartered there. Pabst and some of his officers were determined to kill the two prisoners. He phoned Gustav Noske to get permission for the execution, but was told that he first had to obtain approval from the Commander-in-Chief of the Provisional Reichswehr, General Walther von Lüttwitz. Pabst replied he would never get the permit, whereupon Noske explained that Pabst would have to ‘...be responsible for what he should do’. What followed what was foreseeable.

Karl Liebknecht was the first to be severely mistreated. When he was led to a car via a side exit of the Eden, Liebknecht received a hard blow to his head from a rifle butt. It was struck by a guard, Jäger Otto Wilhelm Rung, and left Liebknecht bleeding profusely and semi-conscious. The car then drove him to Berlin Tiergarten where Liebknecht had to get out and was allegedly shot ‘on the run’ after a few meters. The murderers brought the ‘unknown’ corpse to a nearby hospital around 11:15 pm. Meanwhile, Rosa Luxemburg was taken away. Again, it was Runge who gave Rosa two blows with his rifle butt, causing her to go down and pass out. Recent research has found that Runge was bribed by an officer with 100 Marks to hit Liebknecht and Luxemburg, as he feared the two might leave the Eden alive. Rosa was also put in a car, bleeding profusely. Just as the car was about to drive off, Leutnant Herman Souchon jumped on the running board and shot Luxemburg in the head.

The car drove to the nearby Landwehr Canal, into which Luxembourg's body was thrown, and when the soldiers involved returned to the Eden, one of them boasted: ‘The old pig is already swimming.’ Rosa’s decomposed corpse was not found until 31 May 1919, despite the deployment of fire service divers. For almost everyone involved in the murder there were legal repercussions, but the penalties were ridiculously low, not least because the judge sympathised with the accused and their actions.

The day after the crime, newspapers reported the death of the two Spartacist leaders. Friedrich Ebert and Otto Landsberg were shocked. Neither had been privy to what was happening. Ebert considered resignation, mainly because he feared new unrest would break out and Luxemburg and Liebknecht would be declared martyrs. The rift between the USPD and KPD on the one hand, and the SPD on the other, seemed insurmountable after the murders.

BIRTH OF THE WEIMAR REPUBLIC

After the election for the National Assembly was held on 19 January, the now elected assembly did not meet for the first time in Berlin, but in Weimar on 6 February. The city on the Ilm river was chosen deliberately, and not only because Berlin had become unsafe. Weimar is also known as the classic city of Goethe and Schiller, whose spirit was supposed to have a positive effect on the work of the National Assembly. Additionally, Friedrich Ebert met his critics by changing the conference venue ‘to the heart of Germany’, thus addressing those critics accusing him of only wanting to meet in the old Prussian power centre of Berlin.

Subsequently, the first coalition of the Weimar Republic was formed, consisting of the election winners, the SPD, who teamed up with the centre party and the DDP. The coalition's declared aim was to create a constitution for the new state. But Germany did not come to rest during this time. In numerous regions there were repeated strikes and attempts to form a soviet republic. The bloody climax of this second wave of the revolution was the March massacre in Berlin.

On 3 March 1919, the ‘General Assembly of Workers and Soldiers Councils’ in Greater Berlin decided to call for a general strike the following day. Here, the aim was to form an armed revolutionary workers' force, to dissolve the Freikorps, release political prisoners and recognise all workers' and soldiers' councils. On the day the strike was announced, the Prussian government imposed a state of siege in Berlin. With that, executive power passed to Gustav Noske, who had meanwhile been appointed Reichswehr Minister.

When the general strike began the next day, Noske ordered the Generalkommando Lüttwitz to bring its troops to Berlin. A total of 31400 men moved to the capital, including the Garde-Kavallerie-Schützen-Division. On that day, there were shoot-outs between government troops and republican vigilante groups - as well as remnants of the Volks-Marine-Division. To put further pressure on the government, the strike on 6 March was extended to include essential infrastructure (gas, water, electricity supply). But the hoped-for effect did not materialise, so the entire action was canceled on 8 March. But that did not end the fighting. On the contrary, it continued unabated.

ARBITRARILY EXECUTED

Civil war raged in some parts of Berlin, especially in the east of the city, with artillery, machine guns and tanks brought onto the streets. The struggle between government and insurgents escalated exponentially. One of the reasons was Gustav Noske's shooting order, issued on the basis of the rumour that Spartacists had killed 60 police officers in the Berlin district of Lichtenberg. Noske let everyone know how things stood: ‘Anyone found fighting against government troops with weapons in hand will be shot immediately.’

The Lichtenberg rumour was found to be untrue a few days later, but by then, it was already too late. Government troops had taken the rumour as fact and there were numerous murders, mainly of alleged or actual Spartacists. On 10 March, Leo Jogiches (KPD), a friend of Rosa Luxemburg, was arrested and shot. The Freikorps also took bloody revenge on the men of the Volks-Marine-Division, the Christmas battle of 1918 was not forgotten.

On 11 March, 29 people's sailors were captured, selected and arbitrarily executed. The officer responsible for the execution was later acquitted in court because he ‘only’ carried out the orders of a superior. Last, but not least, completely uninvolved people continued to die. One perpetrator was 23-year-old war veteran, Max Marcus, a patrol leader in the Lützow Freikorps. On 12 March, Marcus had the Lange Strasse in Berlin's Friedrichshain cordoned off to search houses for insurgents and weapons. He shouted: ‘Clear the street, close the windows’. When something stirred at a window on the third floor of a residential building, Marcus shot. But instead of an insurgent, his bullet hit a 12-year-old girl in the head. Marcus also executed other civilians with no apparent involvement and was later sentenced to six months in prison for ‘embezzlement’.

The carnage finally ended on 13 March, and according to conservative estimates some 1,200 people lost their lives in Berlin during the March fighting, some dying in massacres. Of these casualties, 75 were government troops. The revolution then shifted mainly to Munich, where troops loyal to the government helped to bloodily suppress the Bavarian Soviet republic. But that is another chapter in Germany’s bloody post-war revolution.

Oberste Heeresleitung, Supreme Army Command

Private paramilitary groups that first appeared in December 1918 in the wake of Germany's defeat in the war. Composed of ex-soldiers, unemployed youth, and other discontents and led by ex-officers and other former military personnel, they proliferated all over Germany in the spring and summer of 1919 and eventually numbered more than 65 corps of various names, sizes, and descriptions. Most were nationalistic and radically conservative and were employed unofficially but effectively to put down left-wing revolts and uprisings.

The two battalions of the Garde-Fusilier-Regiment united annually in May in Potsdam for drill excercises. The II. Batallion, due to its colourful regimental uniform (red Swedish cuffs with white braid, yellow shoulder boards and brown piping), was greeted with the cry of "Cockchafers!". The name quickly spread to the entire regiment and became quasi-official after Frederick William IV, as Crown Prince, once addressed the regiment as "Maikäfer". Hence their barracks were also called Maikäferkaserne.

Brilliant. Fascinating, in depth account of the chaos in Germany at the end of WWI. A great tragedy. Thanks Rob

What a fascinating read - I hope that there will be a follow up about the events in München