AN INTRODUCTION BY THE EDITOR

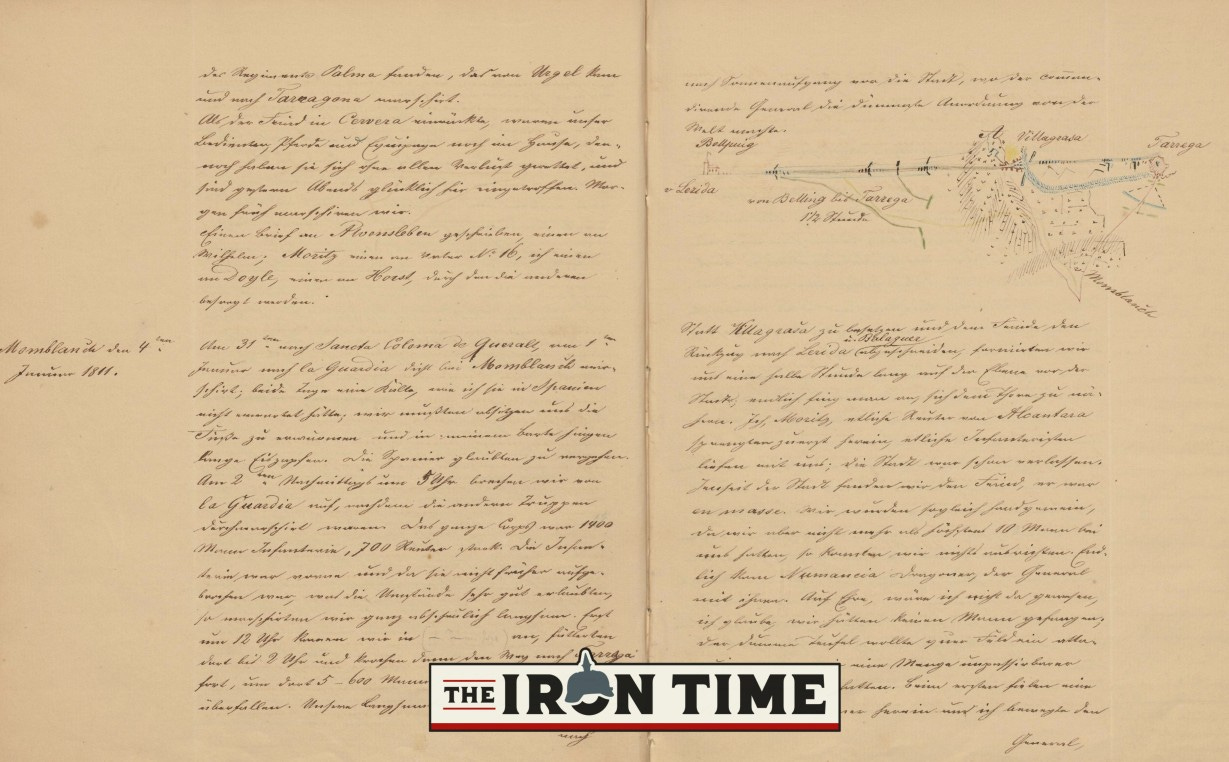

This book is based on the journals of the two young Prussian cavalry officers. One is the diary of Eugen von Hirschfeld who during the Napoleonic Wars, at the side of his beloved brother Moritz, gained fame in Germany and Spain as a resistance fighter, Freikorps leader, duellist and cavalrymen. Having first fled to England with the Schwarze Schar [‘Black Host’] of the Duke of Brunswick, both men joined Spanish service during the Peninsular War. The brothers were keen observers and journalists, and both kept a diary in which they recorded their tribulations and adventures in England and experiences in the service of the Spanish crown. When Eugen von Hirschfeld was killed in battle in January 1811, his anonymous diary was taken by his brother Moritz, who continued keeping it with his own, also anonymously. After the Battle of Saguntum on 25 October 1811, it was taken from the presumed dead Moritz von Hirschfeld and came into the possession of Italian General Giuseppe Federico Palombini1, with whose troops the brothers had crossed swords several times before. In 1843, Palombini was living as a retired Fieldmarshal-Lieutenant of the Austrian army in the province of Saxony on the Grochwitz estate, which his wife had inherited. Next door lay the Wiederau estate, which was the ancestral home of Moritz von Hirschfeld's wife Ida von Kamptz. In conversation with her, Palombini was finally able to identify the authors of the diaries he had kept for so long, and immediately sent them to Moritz von Hirschfeld. After Moritz's death, his friend General Heinrich von Holleben published a small edition of a slightly shortened version of the diaries on the 50th anniversary of the institution of the Iron Cross in 1863.

I recently rediscovered the original, bound journals and notes of the brothers in a German archive, including several watercolour maps and paintings Eugen created in Spain. Eugen’s diary is framed by the memoirs written by Moritz von Hirschfeld, based clearly on his own diaries, as well as several letters, and thoughts on tactics and the equipment and deployment of cavalry. Of great interest are notes in the margins, some by General Palombini, who comments on certain events from his own perspective, and by General Heinrich von Holleben, who added historical and factual remarks. Being in a position to compare the 1863 publication of the diaries with the original manuscripts, allowed me to include the material which Holleben2 didn’t make use of. I also added historical and biographical footnotes in an effort to underpin this superb swashbuckling tale of travel, adventure and war with further interesting information.

BORN TO WAR: THE BROTHERS VON HIRSCHFELD

In autumn 1806 the French conquest of Germany had been completed, thus ending a whole series of wars which had been raging since the early days of the French Republic when the armies of Revolutionary France, thwarting half-hearted Prussian and Austrian efforts to stop them, had taken control of the Rhineland in 1794. In the years which followed, a number of coalitions of allied powers failed to stop France from marching its armies deeper into Germany where more and more German principalities, motivated mostly by fear and French force of arms, yielded to their new masters. Others, making a beneficial choice, rushed to side with Napoleon; as did Bavaria and Wurttemberg, who harboured long-standing grievances against Austria and Prussia.

Since 1805 the number of German contingent troops marching as part of Napoleon's forces had steadily risen. In December that year, France had crushed Austria and its Russian allies at the Battle of Austerlitz. So great was the French victory and so crushing the Allied defeat, that France could begin to remodel large areas of central Germany according to its own strategic interests. The Holy Roman Empire, which had lasted for a thousand years, was dissolved on 6 August 1806 and Francis I of Austria abdicated as Holy Roman Emperor. German rulers loyal to the French Emperor were rewarded and elevated, receiving titles and lands. Dozens of smaller principalities in Western and Southern Germany were wiped off the map entirely when Napoleon formed the Rheinbund, Confederation of the Rhine, in July 1806. Instead of being tied to the Holy Roman Empire and as such to Austria, the many smaller German states within this new entity would now be dominated by France and Napoleon Bonaparte.

Prussia, only two generations after the rule of Frederick the Great, was isolated in foreign policy, having failed to use the ten years of peace since 1795 for domestic reforms. Until 1806, Prussia was the only large central European state that had not yet been engaged in war with Napoleon. Since the Peace of Basel in 1795, in which Prussia had left the coalition of France’s opponents for the time being, it had maintained its neutrality, and cooperating with France had benefited from this policy. However, it also became increasingly apparent that the Prussian government was very shaky and weak. The two remaining major continental powers, France and Russia, put Prussia under pressure. Each in turn made it clear that it would disregard Prussian neutrality if it did not join them if asked to do so. In 1806, Napoleon had succeeded in luring the Prussian government into a political trap. He had allowed Prussia to annex Hanover which was in personal union with Britain. For permission to annex Hanover, Prussia had to close the ports of northern Germany and thus participate in the Continental blockade against France’s arch enemy. This unwise decision of Prussia had severe consequences, as it made any kind of future alliance with Britain impossible. In early 1806, having witnessed the creation of the Rheinbund and having learned of Napoleon’s offer to trade Hanover back to Britain, King Friedrich Wilhelm III’s patience finally ended and on 9 October 1806, in a most unfavourable moment, Prussia declared war on France. Active participants in this new war, which for Prussia would end in a catastrophe, were Eugen3, Moritz4 and Alexander Adolf von Hirschfeld5.

There was a time when ‘von Hirschfeld’ was a name which would have been commonly known all over Germany. It was a name children would learn about in school, where it would be mentioned alongside other household names in the pantheon of the German national heroes of the Wars of Liberation, like Friedrich Ludwig Jahn6, Major Ferdinand Schill7, Major Ludwig Adolf Wilhelm von Lützow8 and Lieutenant Theodor Körner9. Eugen and Moritz von Hirschfeld gained fame not only in Prussia, but also in the Kingdom of Spain, for the liberty of which they chose to fight and for which one of them made the ultimate sacrifice.

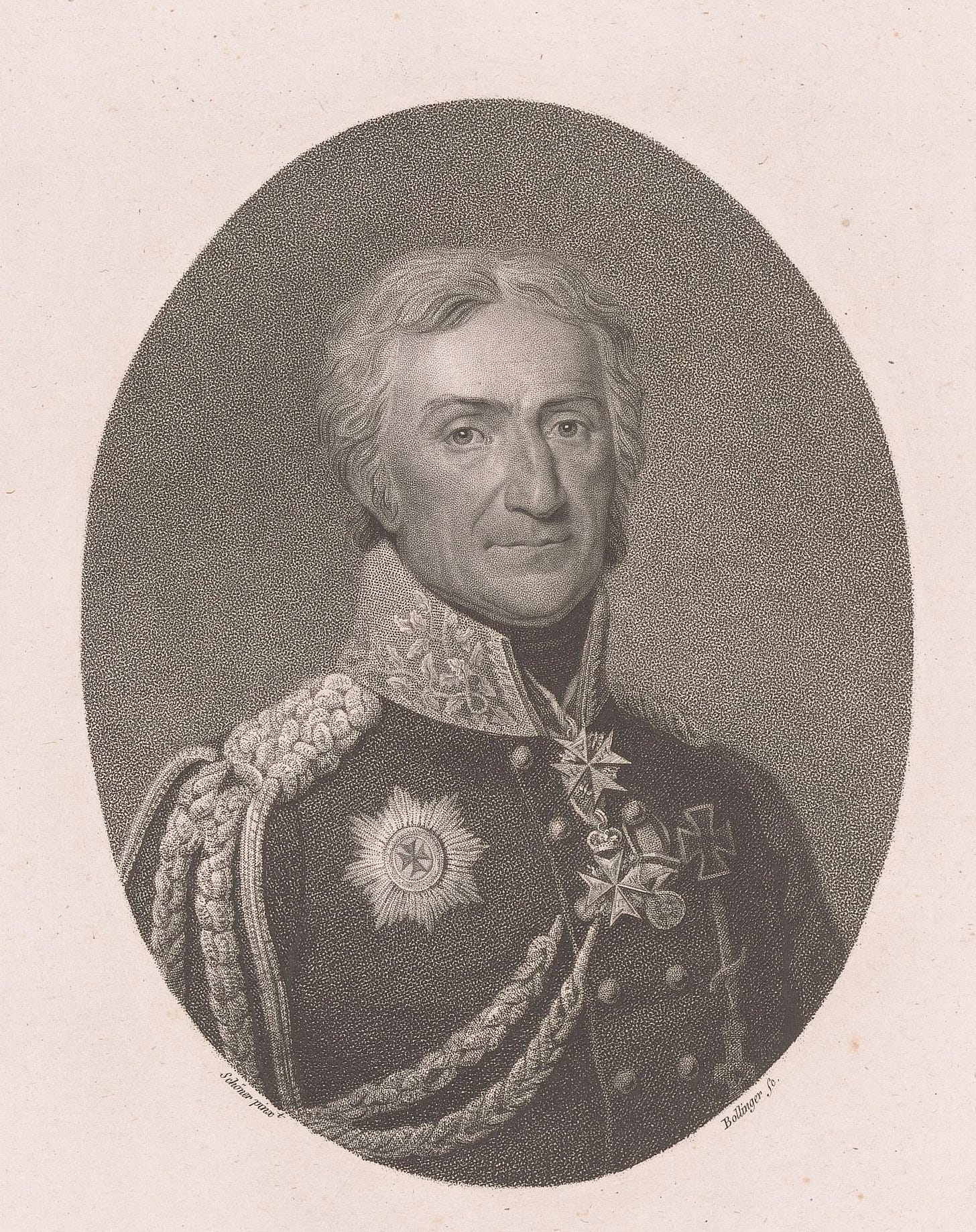

Eugen and Moritz von Hirschfeld were the sons of the Prussian General Karl Friedrich von Hirschfeld10 from his first marriage to Karoline von Faggyas. Both spent their early childhood on the family estate in Gasterleben and as was custom among the male offspring of the Prussian nobility, their military education started early. When he was eight years old, Eugen accompanied his father to war against the Armée du Rhin, which had been purposed to carry the French Revolution and its ideas to the German states along the Rhine. Only two years later in October 1794, the 10-year old boy was commissioned as an Ensign in the Prussian Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 21 ‘Herzog von Braunschweig’, in which his father then served as Adjutant. In 1799 he was promoted to Lieutnant and in January 1803 joined 1. Battalion Garde in Potsdam, which his father had taken over as commander a year before.

In the same month his younger brother Moritz enlisted as a pupil in the Prussian Cadet School in Berlin and a year later, on the occasion of his 14th birthday, his father recruited him into his own regiment as a Gefreiter [Corporal] before releasing him to join the Akademie für junge Offiziere der Infanterie und Kavallerie11. All three12 Hirschfeld brothers briefly served together in their father’s regiment until July 1804, when Eugen was transferred into the Husaren-Regiment ‘Köhler’13. In the Franco-Prussian War of 1806/07, all brothers took part in the Battle of Auerstedt in which Napoleon's troops crushed the Prussian Army. The de facto destruction of the Prussian military paved the way for Napoleon to quickly reach Berlin, where he arrived as early as 27 October and took possession of the undefended city. The Prince of Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen, cut off from news from the high command, had already surrendered at Prenzlau in a misjudgment of the actual troop strength of the forces pursuing him. Within the next weeks, this was followed by a surrender of all the fortresses in the country, with the exceptions of Danzig, Graudenz and Kolberg.

Although on 7 and 8 February 1807 the rest of the Prussian Army, now united with the Russians on the battlefield of Eylau, forced Napoleon to leave the field if not as a loser, then at least not as a victor, the French defeat of the Russians at Friedland on 14 June 1807 nullified this success. Napoleon and the Tsar, without consulting Frederick William III, agreed on a peace in Tilsit on 7 July 1807, to which Prussia had to accede on 9 July. Moritz von Hirschfeld was caught up in the Prussian surrender at Prenzlau on 27 October 1806, as a result of which his father’s regiment was disbanded. On his word of honour not to continue to serve in the ongoing war, Moritz gained his freedom and returned home to Gartersleben on half-pay.

DER KLEINE KRIEG - THE LITTLE WAR

After the Prussian Army’s defeat at Auerstedt, Eugen von Hirschfeld participated in Blücher’s withdrawal across the Elbe river, where he participated in several skirmishes with pursuing French detachments. During one of those, on 1 November 1806, he was wounded in the head by a musket ball. Six days later he was taken prisoner during the Prussian surrender at Ratekau, but managed to escape with the help of a French officer, who only a few days before had himself been Hirschfeld’s prisoner. To show his gratitude for having been treated well, the Frenchman furnished his captive with a passport, which allowed Eugen von Hirschfeld to escape. Accompanied by his friend and fellow officer Lieutenant Wilhelm von Rephun of the Husaren-Regiment von Rudorff, he made his way to Kolberg, evading French patrols and at least once pretending to be French officers to avoid being captured. In Kolberg, Eugen then reunited with his brother Moritz who had escaped after breaking his parole. Both then briefly attached themselves to the Freikorps of the legendary Major Ferdinand von Schill. For their father, who had at first been released from French captivity, his son's actions resulted in an immediate arrest by the French. Held captive in Magdeburg, he was only released in July 1807.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to THE IRON TIME to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.