BROTHERS OF THE BLADE: TWO LIVES AGAINST NAPOLEON (3)

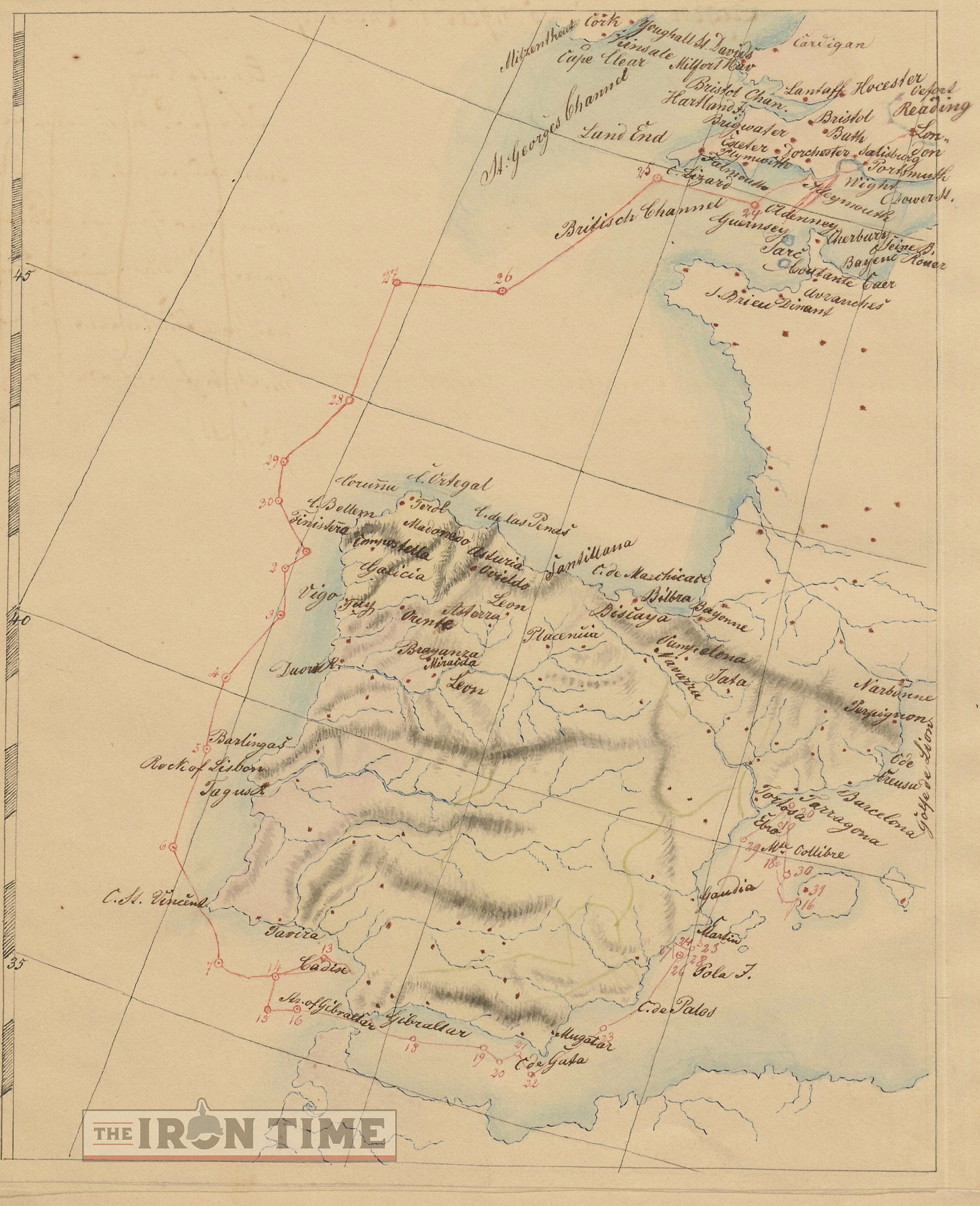

INSTALMENT NO. 3 : DIARY OF EUGEN VON HIRSCHFELD 4 JUNE to 11 SEPTEMBER 1810

We continue here with the first entries in the diary of Eugen von Hirschfeld, starting in Portsmouth on 4 June 1810.

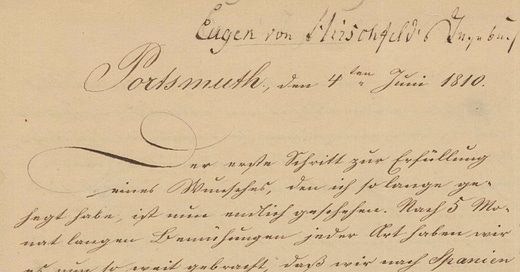

DIARY OF EUGEN VON HIRSCHFELD

Portsmouth 4 June 1810

The first step towards fulfilling my wish, which I have cherished for so long, has finally happened. After 5 months of efforts of every kind we have now got so far that we are going to Spain to try to set up a German corps there. All attempts to be allowed to go to Spain under any conditions and without any demands, just to gain experience, remained fruitless. In England everything follows immutable laws, and the most beneficial possibilities are often discarded; above all, however, one is extremely suspicious of all strangers and proud of oneself. Even my repeated requests just to let me go there without any support and on my own responsibility were in vain, and I would still be in the same spot today, had Schepler's1 plan not now been carried out, which by the way deserves credit for having overcome the distrust of the English. This then for the news of my acquaintances, who may be surprised that I let such a long period of time go by unused. We left London last night after a really painful farewell to Moritz. It was a tormenting thought to have to leave the poor boy so lonely in that immense city, and yet it could not be helped as he must not sacrifice a safe situation for uncertainty, which is not advisable in these times. He was also very touched himself and gave unmistakable signs of his brotherly attachment to me. Then it fell on my heart, as I had sometimes been so strict to such a good boy, and it certainly made my heart ache. With a thousand sacrifices I would like to buy back every unkind word in order to escape this bitter memory, although in general I certainly believe that I have completely fulfilled my duty as a brother and friend. We have arrived here today, but we do not know the day of our embarkation and we await it with great longing.

Aboard the Justicia in Portsmouth Roads , 10 June 1810.

At last we are finally on the water, although we still do not know whether we will still be sailing today. We have now spent six days in uncertainty and had to use up the money we had put in. Our whole fortune, with which all three of us have to travel to Cadiz, consists of 2 pounds 18 shillings 6 pence. Another proof of how difficult it is to travel to Spain. Each of us received 50 pounds for the trip; I had no debts and only bought what was necessary, although I left money for Moritz. Now I have to live on a mere ship's fare and significantly worse than the common seaman, who because of the hard work gets a third more of everything than everyone else. Everyone embarking on a royal transport gets free provisions; Nota bene2, however, the first officer by no means more than the lowliest soldier. The wind changes, it has now risen once more; we have had no wind for a number of days so it is uncertain what kind of wind we will get. I would have liked to have written a few words to Moritz this morning; but the Captain has gone to the city without telling us anything about it, and otherwise there is no more opportunity. Nota bene we are one English mile from the coast.

Portsmouth, June 14

Letter no. 4 written to Moritz, informing him that we will be sailing by tomorrow, because the wind is pretty good, and the frigate that is accompanying us has put up a signal that the convoy should get ready to sail. The soldiers like to call this signal, which they are very familiar with, 'salt beef', because from then they usually have nothing but salted meat in front of them for a long time. Schepler and Oppen3 went into town to collect 5 pounds, which the latter is supposed to receive there. This really saves us from quite an embarrassment, because it's no fun to travel to Cadiz with less than a pound, and half of it is already spent, since decency does not allow you to live on the ship's fare for as long can get something else and at such things the Englishman is far more of a fool than any other nation. In Germany you are a poor devil if you have no money, in England you are a downright scoundrel. A person of rank who is believed to have little or no money is being downright maltreated. Our wish was therefore that we should go to sea very soon and then be driven around for a long time by an adverse wind, because this is the best way to secure our remaining finances.

Same, June 15.

All those who know me well know how uncomfortable I find the approximate; today I was put to the test in this respect. We have been lying here for twelve days and had the promise to leave immediately. Finally the wind has been favourable since yesterday, i.e. it comes from the north-east; this morning the signal is given to have everything ready; - but lo and behold, suddenly the wind turns again and comes from the opposite direction (south-west); So it went full circle in 24 hours, from the south-west and back again: its enough to drive one to insanity. By the way, we will travel in strong company; many ships will travel with us, and a frigate and a brig to escort them. Next to us is a Spaniard who will also sail with us. I have not yet noticed anything special about him other than the fact that the prayer bell sounds to us three or four times a day. Today we also got a travelling companion in our narrow cabin, with which we are dissatisfied; It's been a pretty uncomfortable day today.

In the Canal at Comes, at 1 PM, 16 June

Finally we have weighed anchor and are sailing down the lovely canal which the south coast of England forms with the Isle of Wight. On the left the shore of the island, the garden of England; an indescribably charming sight, alternating the most beautiful beech forests, old castles, modern villas, towns, villages and hills; on the right the green meadows of England; very close - because the canal is narrow - the coast, beautifully overgrown and gloriously green; furthermore Southampton with its beautiful gothic castle; both banks are strewn with inviting country houses and looming castles and forts; a beautiful, beautiful sight. This is the fifth time I've been doing this tour and the area seems more and more beautiful to me. Now we will soon see the Yarmouth and Freshwater area where I lived for a number of months. I remember these times with sadness; whoever knows my story will understand me. Half an hour ago I also wrote two lines to Moritz (without a number) to let him know that we have sailed . A boat that landed another passenger after we had been sailing for an hour gave us the opportunity.

In view of the west coast of the Isle of Wight , 17 June

We dropped anchor at Yarmouth last night and set sail at 4 o'clock this morning. The wind was so weak and the rushing tide so strong that we often didn't move at all for half an hour. Now the wind has turned again and is north-west, but still not stronger.

In Weymouth Harbour, 19 June.

The wind turned even more yesterday and became quite westerly; so we had to be happy to reach this port; with the adverse, but still stronger wind that persists today, we would certainly have been thrown back to the Needles. Yesterday I also wrote to Moritz (No. 5) and asked him to write me here, especially how things stand with the Duke; maybe the letter will reach me here

21 June

Still here , still contrary wind , my old , eternal Areuz . - I have written to Moritz (No. 6) and commented on the possibility that he might still come later.

Friday, 22 June

Today the wind turned a little to the north and as one certainly believed it would move even more, the anchors were weighed and we set sail; but my patience is being slowly pushed to the limit; before we were out of the harbour, the wind calmed down and although all the sailors and soldiers swore that we would get an easterly wind throughout today, it is gradually turning to the west again. Now both inconveniences are combined as far as that is possible; we can't get away, and I can't go ashore to look for letters either, because there will probably be one from Moritz which I'm very curious about. I fell out with Schepeler today and we will shoot at each other as soon as the anchor is dropped. The anchors are dropped; but since Oppen and Schepeler consider it better to deal with the matter only after our affairs in Cadiz have been decided, and I also accept this, I have agreed - no matter how uncomfortable this is for me; because I don't know anything more embarrassing than being almost locked in a room, a miserable little hole, with a person with whom you have such business.

23 June, 1 p.m.

Today we sailed from Weymouth early in the morning and the wind is good and fairly strong, so we have already lost sight of the coast of England for several hours. Tomorrow morning we expect to be off Plymouth, where another convoy will join us. Now we count 46 sails, excluding the Frigate and sans the convoy that leaves us again at Plymouth.

Después de comer, Ni sobrescrito ler4

June 25, Monday. 5° 50' longitude, 49° 16' latitude.

Today we are in the Bay of Biscay, and I remember the wish I often expressed to Moritz during our stay in Guernsey: 'If only I could spit into the Bay of Biscay.’ Half of the wish has been achieved, and I just don't quite feel like trying to achieve the other half, although I have my eyes set on the fulfilment of the same, because although I have behaved gallantly up to now, the swell here is too rough because of the unfathomability and depth of the water.

26 June. 8° 14' longitude, 47° 53' latitude.

Actually we are not in the Sea of Biscay, which was avoided because of the usual westerly winds, but in the great ocean. The waves are really decent and make everything very difficult, as we can only sail slowly because several ships are very poor sailors. The war brig, which is with our escort, has just brought up two Danish merchant brigs right in front of our eyes. Judging by the direction, they are coming from North America or the West Indies; We don't know the exact details yet, although we're only 100 paces apart. - Both were released again because they had English passports.

27 June. 10° 16' longitude, 46° 27' latitude.

Although we have not passed the Bay of Biscay, we have experienced and are still experiencing its peculiarities to a high degree. The waves are always very high here, even when there is no wind, because the water is so deep that up to now no sinker has found ground. We are now being tossed about in a moderate wind as if we had the worst gale, so that sometimes I lose patience altogether, especially at night. Everything is either thrown out of one's hands or broken in one's hands; what is not tied is broken in two. Today, in the true sense of the word, merry flocks of dolphins were joking around our ship; 20 and 30 of them came around us very closely and twirled around the ship; you can really see how rampant and cheerful their movements are. The dolphin is four to five feet long, in the middle probably as wide as Moritz in body, and has a very pointed head; dark grey on the back, the belly completely white. Often they come out of the water in high leaps of three or four feet, one behind the other, as if they were all leaping out of one hole and into another.

28 June. 10° 35' longitude, 44° 56' latitude.

We have now reached the north-western tip of Galicia and are sailing around it today, but without seeing it as we are a good 30 German miles away from it.

29 June. 10° 56' longitude, 43° 29' latitude.

We had a very light wind all night and it's not much stronger now so we didn't get as far as we hoped. We shall now be roughly opposite Finisterre. Yesterday evening I noticed that the sea here glows in the dark when it is stirred up, just as much as we saw when we sailed out of the mouth of the Elbe. It is an exceedingly beautiful sight and kept me entertained for over an hour; how this bright, almost magical fire floated around the keel of our ship and lit up the prow; how afterwards the fiery furrows marked the way we had been going, and how the ship crossed the ocean with a glowing tail behind it. The other ships too are looking beautiful, seemingly gliding along on the glow surrounding them. Two sharks showed up around the ship this afternoon, but I didn't see them; however they are said to be quite common here, and in Cadiz and environs they are even eaten by the Spaniards. The climate is also becoming noticeably warmer. By the way, we probably won't get very far today because the wind has become very weak, almost calm.

30 June. 11° 57' longitude, 42° 59' latitude.

Unfortunately, the wind is very weak, also from the south-west, which is why we only made 50 English miles of progress. We are on the level of Cabo de Finisterre, and 90 English miles away. If it stays that way, we're worried about staying at sea for another 14 days, but we're still hoping for a change.

1 July, Sunday. 9° 50″ Longitude, 42° 25′ Latitude.

The wind has turned all the way to the south , so we steered south - east for the night and at daybreak we see the coast of Galicia ahead of us. They are high, grotesque mountains; we are too far away to see their nature in more detail.

2 July. 10° 13' longitude, 42° 9' latitude.

We are opposite from Vigo and are now always sailing along the blue mountains.

3 July. 9° 53' longitude, 41° 20' latitude.

We alternately had bad wind and no wind at all, so we had to leave the coast again and are only making little progress. Today we are opposite Oporto but more than 20 German miles away; so we don't see it. It's getting very warm now; it is no longer bearable in the cabin. Tomorrow we hope to be at the roadstead of Lisbon; but of course the wind is beginning to get weak again.

4 July, 40° 9' latitude.

Today we see the rocky Berlengas Islands lying off the Portuguese coast north of Lisbon.

July 5th. 10° 10 longitude, 38° 56' latitude.

There lies the Rock of Lisbon, great and proud before us; the whole coast of Portugal can be clearly seen. At first we thought we would get there in several more days; but it's over now. In a few days we must be in Cadiz, must reach the new promised land on which all my hopes are aimed, all my expectations are directed. It is hot, despite the fresh and pleasant wind, very surprising. We can hardly stand it even in shirtsleeves and with bare necks, and one cannot stay long on one spot on the deck which is particularly exposed to the sun, because the floorboards get so hot that it burns through the soles.

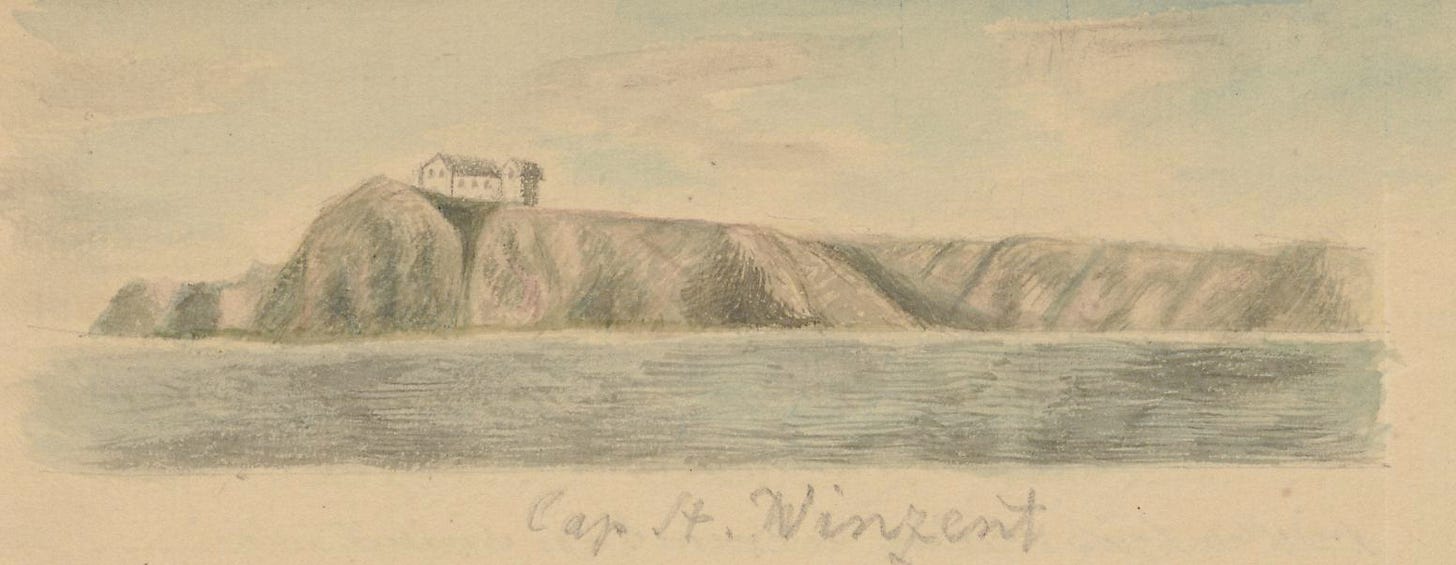

6 July.

Today we see the Sierra de Monchique and think of sailing around Cabo de St. Vincent. It's very hot. I've just seen a shark, the sea hyena, but only just enough that I can have fun telling everyone about it. It passed about 200 paces from the ship, a mighty beast; several feet of its back above the waterline, all black with enormous fins and very long. We all wished to see such a shark up close, and it really made some movements as if it wanted to get closer. Otherwise it tends to follow the ships and is easy to catch because of his greed and rapacity. Because of it, one no longer bathes in these waters, and English sailors and soldiers are strictly forbidden to do so. Cape St. Vincent lies ahead ; we will be sailing around shortly and very close to it.

Half past seven in the evening. We are just passing the Cabo de St. Vincent; a very salient angle of southern Portugal that ends in two promontories. On the northern tongue on the last rocky slope lies the monastery of St. Vincent, where nature has ceased to exist. Only in the hot climate of Spain, where exuberance thrives so splendidly and has borne such bloody fruits, can the monastic spirit make such dead regions a place of residence for godliness. The walls stand vertically on the immense rock masses, behind you an endless desert and in front of you the ocean. No tree, no bush, yes, no fresh blade of grass sprout here to offer rest to the tired eye. There is a fort on the southern tongue of land. Incidentally, we sailed closer to the cape than is usually the case.

7 July

The wind is weak and worse, comes from the opposite direction, as if it was made in Cadiz and came the shortest way from there; So now we, hoping for a better wind, are heading towards the coast of Africa. It's terribly hot; the floorboards are burning under the soles of my feet, tar and pitch are melting, and although I'm dressed as thinly as possible, it's still hard to bear. Fish swarm around our ships twenty feet long, immense beasts; They have a hole on top of their heads where they squirt out the water like a whale, and when they get up out of the water, which happens all the time, they snort like a horse after a long ride, often three or four at a time, as if cavalry is all around us.

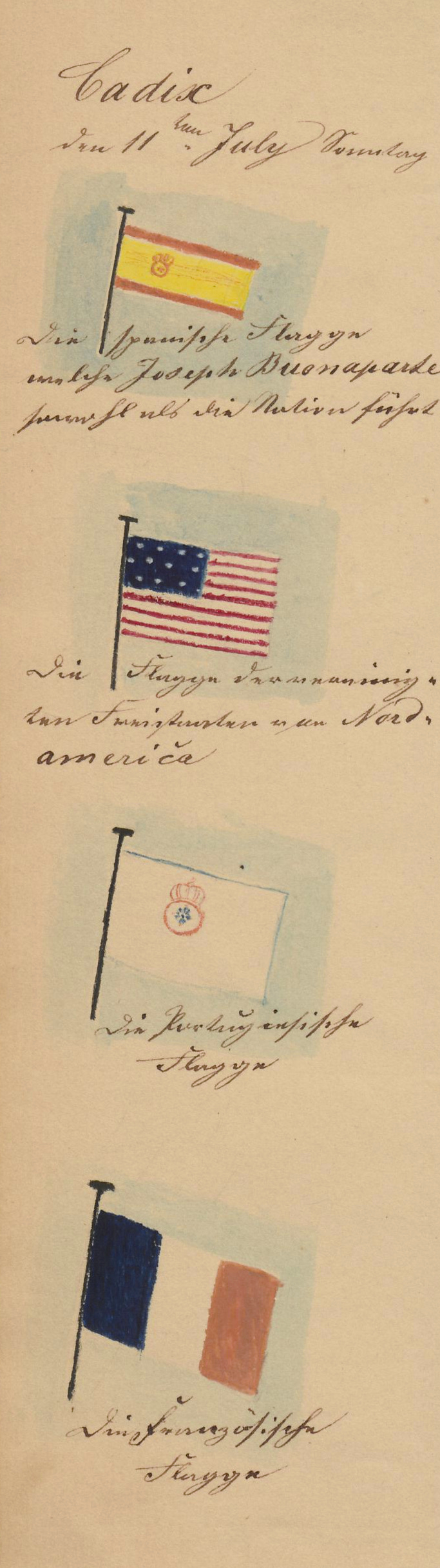

Cadiz, 11 July, Sunday.

Written to Moritz. No. 7. Here I am in the city on which the eyes of the world are directed, whose outline I have examined so carefully, whether the news of its fall is to be feared, whether this bulwark of freedom will share the fate of many a beautiful Spanish fortress. But I am completely reassured about that; Its location makes the place as insurmountable as long as Spain and England are friends. On one side the sea, on the other side the harbour where a huge fleet lies. The place itself is connected to the island of Leon, which is also strongly fortified, by a narrow, equally fortified tongue of land, which can also be fired upon by frigates and ships of the line. On the morning of the 8th, when we got up, we had the most magnificent sight of Cadiz and its surroundings: the city, beautifully built, with its bulwarks, towers, castles; the immense fleet, on the left the coast of Spain, lined with castles, country houses, beautiful places, towers, etc., on the forts the Spanish flag of Joseph Bonaparte, who flies one and the same flag as the nation; the ocean on the right, mountains in the background. We entered the harbour and were ashore at noon. After much futile searching we finally found a little room, five stories high, small, dirty, stinking, but with a delightful view: the harbour, the opposite shore, where we can distinguish the French batteries, even single Frenchman, with our good binoculars; further back on a high mountain Medina Sidonia, in the background the Sierra de Ceres with its grotesque shapes. Cadiz is sufficiently provided with everything; also has cistern water in abundance. Fresh meat is rare, everything else is available in abundance, especially a large quantity of the finest fruits that the South produces. The houses are beautiful and high, the streets narrow, making them shady and cool; every window is a balcony where the beauties are almost always visible. The roofs are flat. The people have a very dark yellow complexion, piercing, dark eyes and some of them have very conspicuous clothing. The Spaniard, however, seems to have a different character than we have hitherto believed; Cheerful, careless, vain and conceited, but tolerable. His demeanour is pleasing, secure, easy, and his social nature contrasts favourably with John Bull's loutish behaviour. The city is full of people, some of them military. One sees a hundred different uniforms there, as in 1807 in Königsberg, the remains of the broken regiments are assembled here. The condition of the troops, especially the cavalry, is pitiful. But there are also Englishmen and a regiment of Portuguese here on the island. The total number of troops should be 18,000 men; also a lot of militias in the city. All residents are armed. Shots are fired from time to time, but no ball or shell reaches the city or fort, not even the ships.

In general, the place is incredibly strong and will probably never be taken by the French as long as the English and Spaniards remain friends. They eat little here because of the heat, except for fruit; but there is drinking all the more; a need necessitated by climate. The Spaniard usually drinks wine and water. You rarely see drunk people.

12 July.

Yesterday we sat down with Wellesley5, he is a brother of the conqueror of Talavera, minister and ambassador to the Junta of Cadiz. They were extraordinarily nice to us, and yesterday I got to know a different side of John Bull, which I really liked. Behaviour among one another is indeed very nice, so friendly, so trusting, generals and officers; the general offers the young officer his hand and shakes it, all differences seem to have come to an end. In general, the English generals are extremely well-behaved, generally educated people, and they usually speak several languages, mostly French. After dinner, I went with von Oppen to the Almeida, where towards the evening everyone is strolling. A part of the rampart is lined with trees on the north side. Old and young, noble and humble come here and cavort happily among the happy ones. Cannon shots sometimes rumble through the hum of the crowd; but you hardly seem to notice it. I have now also acquired a Spanish cockade, black and red, with the cipher 'FF' embroidered on the inside in gold. It is the English attention to the Spaniards that appeals to me; they mostly wear them, even the commoners. We haven't received quarters yet and it is possible that this will drag on for a while. Today I'm thinking of going to the island of Leon with Oppen to visit Grolman6 and at the same time take a look around there. I got money yesterday. Lerida and Mequinenza have fallen and the displeasure and tension among the military is great. O'Donnell 7had to flee, but it should be pretty much all right now. They do not want to recognize the current constitution and only want to submit to the person of Ferdinand VII. The consequences are not yet known. Victor is quartered across the harbour in Sancta Maria; we can see the house very clearly from our window. The address I sent to Moritz is: 'Captain Lützow at Gordon Shaw et Comp à Cadiz.'

14 July.

We have just returned from the island of Leon, where Oppen and I went yesterday around noon to visit Grolman, Dohna8 and Lützow9 and at the same time to see the situation and defence of the island, of which we have the most favourable opinion. The Spaniards have deployed a mass of artillery such as I have never before seen. The whole position is actually very good. We got to the outermost outposts, which are very close to the French but have orders from both sides not to fire at each other unnecessarily. On the other hand, the French had set up two new batteries at about 1500 paces from our outermost battery; there was therefore fairly heavy heavy artillery fire on both sides, and as we were walking straight down the line of fire in returning from the outposts to the battery which was being fired upon in particular, several 16-pounders came fairly close to us. The cut-though terrain results mainly from the fact that the lower regions are traversed by wide canals, leading into a kind of shallow ponds, in which sea salt is collected. In front of the bridge, which forms the exit from the island, there are 7 batteries, 3 of which have 32 guns in total; in addition, however, there are still several strong batteries further away. The river that separates the island of Leon from the mainland is narrow, but so deep that ships of the line can sail as far as the bridge, and there are actually two former French vessels on it, which were taken by the Spaniards in 1808. In addition, however, a large number of gunboats contribute to the defence of the island. Such small trips are usually made in a charriol with a strangely decorated horse or mule waiting on street corners for passengers. One pays 2 to 3 pesos for such a vehicle from here to the city of Leon. Here in the tavern I eat about 2 1/2 pesos a day.

15 July.

In speaking, the Spanish woman should be quite free; However, further freedoms are not kindly received, and one complains very bitterly about the English jeu de main. – A kiss is something unheard of here and may not even occur in the theatre, so this strange anecdote is really: when they wanted to bring a very pretty French operetta to the Spanish theatre, in which there was a kiss that was so intertwined in the story that something similar had to happen, it was changed so that the girl deloused her lover instead of kissing him! Yes, yes, deloused! – this is a sign of love and trust here in this country, even among very decent people.10

16 July, Sunday.

Yesterday we moved into our assigned quarters (Oppen and I together) and found a very friendly, extremely pleasant host who also speaks French very fluently. Our room is very spacious; we have an entrance hall, a visitor's room with a cabinet, and on the left side of each a spacious room. Looking at the masses gathered in the city this is very rare and quite excellent. This also gives us hope for our affairs and allows us to draw pleasant conclusions, because if we had not been particularly recommended, we would not have gotten any accommodation at all, or at least not as good as this. Luckily, our rooms are very cool and since we live on two sides, we can always avoid the sun. Incidentally, the climate here is such that you always have all the windows and doors open, so there is always a draft. Even the night is spent like this and one is at most covered by 2 thin, linen blankets. That's what the climate demands. On the other hand, the mosquitoes torment me terribly, especially me, since I must have very sweet blood, because in Germany I was a favourite of mosquitoes; here I am already quite colourful because of their diligence and thirst. But I don't blame the little beasts — . My God, how tormented I am by thirst in this heat! Today is father's birthday. – I'll just make a small note, but from this morning on I've been thinking about home and have been letting the images of my father's house pass by my mind's eye. May fate give you all, my dearest, a very happy old age; may there be a spiritual connection between us and may your souls feel how close mine is to all of you. Ah ! Just one letter, so that I can find out how you are doing, because it's been too long since I've had news of you and the times are pregnant with misfortune.

24 July.

General Blake11 has retired from the army because in a few days he will be leaving for Murcia to take command of the army of the centre . The Catalans are said to have recalled General O'Donnell. Our fate is not yet decided. Ciudad Rodrigo has surrendered to the French. The Spanish women are extraordinarily fiery in their whole being and therefore interesting; Otherwise I cannot say that the Cadiz women are beautiful, but one sees beautiful arms far more frequently there and in Germany or England, since the Spanish ladies constantly walk with bare arms, even in the scorching heat of the sun. You have your own kind of bathing establishment here. Between the lighthouse and the small castle on the right, outside the ramparts, there is a place where the tide very seldom enters; it goes down a flight of stairs where you pay a man standing there one real for permission to bathe in the ocean and see hundreds of people standing above (often even women) to watch the fun. Here all men of all ranks go towards evening to bathe. The monks, who are often led into the floods by the dozen, look particularly strange on this occasion. To see the venerable Fathers, so plump, naked with the holy tonsure, anxiously tramping about in the water, is a sight that makes even the serious ones laugh. When it has become dark all the men have to leave, the sentries on this part of the wall are doubled and now the women come, led by their lovers, husbands, friends of the house, etc., often accompanied by 2, 3 or 4 maids. The male guides stay back a few paces from the wall because the sentinels will no longer let any man near them. But now the fun is only just beginning. It is well known that three women make more noise in the water than a hundred men; So just imagine several hundred women and girls from all walks of life, of all ages, together in the water, it's cheering, laughing, screaming, splashing, raging - God forbid! I haven't heard anything like that in my whole life. It's expensive but it's damn it and I can hardly get by here with my salary, which I used to live with Moritz in Guernsey.

27 July

No. 8 written to Moritz with the date 17th and 24th - turned out to be a bit violent, because it is unacceptable that I have not received any letters from my relatives and Moritz in particular has no excuse at all for his behaviour. Address: 'A los Jugla y de Méllet, para entregar al Capitan don Eugenio de Hirschfeld'

29 July , Sunday.

The spirit of the Spanish troops is bad and not warlike; Officers of the higher ranks are mostly men who owe their rank to their birth alone and who show that they are neither soldiers nor want to be soldiers. The generals are almost all old men who look like they can hardly crawl and who are far less martial than even our former Prussian generals. One sees a few young people among them, but they mostly don't know themselves how they got into their position. By the way, the whole town here is full of idle officers, who, however, receive full pay. Since 9 March, they have had the order to go to Catalonia, but the travel money has not yet been paid out and they are therefore still here. The Spaniards fought a lot of battles in this war, but without ever being too successful and they all ran like rabbits at the first cannon shots. Only their German regiments held off the catastrophe and, by sacrificing themselves, gave the Spaniards time to get to safety. In the Battle of Bailén, where Dupont12 was so stupid as to capitulate although he would have been able to destroy the whole Spanish army if he hadn't lost his head, 2 Spanish regiments were attacked by the French infantry; of course they immediately turned around and ran. The Walloon Guards , who were behind it, kept their composure, threatened the Spaniards to shoot them down and called on them to throw themselves on the ground. That's what the proud Spaniards did in front of the Walloons, who now awaited the enemy and repulsed his violent attack, while these two regiments of Spaniards lay in this shameful position in front of them and let themselves be fired over. But they defend their fortresses admirably; here they gave several examples that are memorable.13

Cadiz, Friday, 7 September 1810.

The present state of Spain, as far as I am able to judge, is as follows: (As I do much business here with the Regencia, I believe I am able to give a fairly correct judgement as to the running of the to be able to deal with public affairs). The kingdom is ruled by the Regencia on behalf of the king, at least everywhere where there are no Frenchmen. This regency consists of four members and a president, who is General Castaños14. As great as his reputation was in Germany, he didn't deserve it; however, he has nothing less to enjoy than the confidence and respect of the nation. The other members have the best intentions, but cannot cope with their important sphere of activity, which is why everything is carried out lazily, slowly and miserably beyond all description. The army and especially the cavalry is so bad that one must have seen the Spanish oneself to believe it is possible that such troops can exist at all. Also, their existence would have long ceased if the French would advance in Spain with the same force and speed that we are used to from them in Germany; but with them everything also goes lamely; they have lost their breath and courage. In fact, the entire war on the Spanish side is being waged by the guerrillas. These are scattered throughout the empire and wear out the enemy to the utmost, who is not safe from them in any part of the country for even a moment. The armies are divided as follows: In Catalonia, General O'Donnell commands. This is supposed to be a man of strength and talent. In the Pyrenees he still has the fortress of Urgel and a division that had recently broken into French territory again. Besides the garrisons of Tortosa and the corps that observes Barcellona, he has at most 8,000 men in the Tarragona area. Opposite him is General Suchet with 20-25,000 men. In fact, he attacked Tortosa, but returned to Mequinenza and Lerida without having achieved anything. General Caro is in Valencia with 15-20,000 men. General Bassecourt15 is at Cuenca with a large corps; His detachments are advancing as far as Calatayud and Daroca in the direction of Saragossa and have recently engaged in a number of advantageous skirmishes with the French in these areas. According to the latest news, Caro is said to have been dismissed because people are generally dissatisfied with him because of his irresponsible complete inactivity. Bassecourt is said to have taken command. – In Murcia, General Blake commands the army called the 'Army of the Centre'. It easily counts 20,000 men, but of these only 12,000 men are armed at most. In addition, the Alpujarras are occupied and defended by the insurgents. General Sebaſtiani with 15,000 men stands against them in the kingdom of Caen. He is with his right wing near Malaga on the coast, with his left against Murcia.

Comment from Moritz von Hirschfeld: Blake was favoured by the English Government General and thus, despite his inability, received a command again and again. Wherever he commanded, he was always defeated, and was nothing but an annihilator of armies.

11 September

In the mountains of Ronda the inhabitants are also under arms, and although the French keep hold of the city of Ronda, which is strongly fortified by nature, they do not succeed in disarming those mountain dwellers. The garrison of Cadiz and the island of Leon is 15 to 18,000 men strong, including perhaps 6,000 Englishmen under General Graham. Perhaps in time the French will conquer the island of Leon if the war continues to be unfortunate for us; but that the city of Cadiz will never (like Gibraltar) fall into French hands, that can be foreseen with certainty. It will probably remain in English power if Spain should succumb in the struggle for honour and freedom. Marshal Victor is lying in front of Cadiz with 12 to at most 15,000 men. However, the hilly terrain and the mutually massive entrenchments make both positions unassailable. Victor could only be forced to retreat by significant landings beyond his wing. You might be strong enough in terms of numbers for that, but the Spanish troops are too weak to be able to rely on them. Behind the Guadalquivir near Seville Mortier has his position with perhaps 20,000 men; now he has advanced to Lerena (towards Badajoz), where he faces Romana. In the mountains of Ayamonte, Valverde del Camino and Aracena, on the left bank of the Guadiana, there were about 1500 light troops, against whom the Duke of Arenberg had about the same number; he was at Moguer, where he was expelled by an expedition by General Lasci; but this undertaking has remained insignificant due to mistakes that have occurred. Romana advanced against Seville from Badajoz, he had about 20,000 men. His vanguard under General Ballesteros was defeated in front of Lerena, but Romana maintained the position of Lafra, 9 German miles from Badajoz and 5 miles from Lerena. Recently 3 Portuguese cavalry regiments trained according to English regulations joined him. The English General Wellington is in a very strong, entrenched position behind Almeida in northern Portugal, right on the border of Leon. Wellington is a wise man, but extremely timid and indecisive. His greatest wish seems to be to return to Old England soon. He is the commanding general of all the troops in Portugal, consisting of 25,000 English, 35,000 Portuguese in English pay, and also 24 battalions of Portuguese Landwehr [militia] to occupy the interior and the strongholds. Opposite him stands Massena16, with the great French army, which according to the French reports is 60,000 strong; but he probably wasn't from the beginning, but now he's far from it, despite all the reinforcements, because his losses from contagious diseases are extraordinary and not counting those that the farmers kill every day, indeed every hour. Nevertheless, Wellington does not dare to leave his entrenchments and lets himself be taken one place after another, like Ciudad Rodrigo and now Almeida again, which is directly in front of his position. He has asked for reinforcements, and they send him 10,000 men, who may now have arrived in Portugal; the regiment of the Duke of Brunswick is there. Galicia is all under arms and cleansed of the enemy. In the northern part you face each other on the border; in the south, detachments frequently fought for the possession of Sanabria, which is in the kingdom of Leon. In Asturia a French corps is on the border with Galicia, to where it recently advanced, and since then everything in the province behind them has been in unrest again, with some small towns were even being captured by the insurgents. In Navarra and Biscay the guerrillas have the upper hand and are so numerous that for some time they have even threatened the road from Saragoſſa to France via Jaca. The French governor of this area wrote a very pitiful-sounding letter to the Minister of War, which had been intercepted by the guerrillas and in which he complained about his distress, that although he was governor of the province, he was not allowed to venture out of his city. In general, the French letters, which are very often intercepted, sound pitiful beyond all understanding, even their official reports and prove the misery they live in, how they are tormented by the guerrillas and how fed up they are with the war. It is also evident from the frequently intercepted letters that Bonaparte is very dissatisfied with his brother Joseph, who seems to fear to suffer the same fate with his brother Ludwig.

Andreas Daniel Berthold von Schepeler, joined the Austrian military service in 1799 and served in northern Italy and Dalmatia. He then joined the Prussian army but was forced to leave Prussian service after the defeat of 1806. In 1809 he travelled to Spain and acquired an appointment on the staff of the Spanish army, rising to the rank of colonel. An intelligent and literate man, Schepeler published a history of the Peninsular War in three volumes in German which was translated into French and Spanish and his account of the Battle of Albuera, in which he participated, is of great interest to students of that engagement because it is one of the few eyewitness accounts available from the Spanish side (another being what you are reading here). As a diplomat on behalf of Prussia, Schepeler worked in the Prussian Embassy Madrid until 1823, before returning to Berlin.

Plural form notate bene : Latin phrase meaning "note well".

Karl Friedrich Wilhelm (1778-1814), pupil of Scharnhorst, 1810/12 in Spanish service, killed as Lieutenant Colonel in the Prussian General Staff in the Battle of Vauchamps.

Spanish saying, ‘After eating, not an over-read‘ : Warning of the harm that comes from any effort immediately after eating, including the mental effort of reading.

Henry Wellesley, 1st Baron Cowley GCB (20 January 1773 – 27 April 1847) was an Anglo-Irish diplomat and politician. He was the younger brother of the soldier and politician the first Duke of Wellington. He is known particularly for his service as British Ambassador to Spain during the Peninsular War where he acted in cooperation with his brother to gain the support of Cortes of Cádiz. His later postings included being Ambassador in Vienna where he dealt with Metternich and British Ambassador to France during the reign of Louis Philippe I. He became embroiled in a public scandal in 1809 when his wife Charlotte eloped with Henry Paget who as Lord Uxbridge was later to serve as cavalry commander under his brother at the Battle of Waterloo.

Karl Wilhelm Georg Grolman, from 1786 von Grolman (b. 30 July 1777 in Berlin; † 15 September 1843 in Posen) was a Prussian General of the Infantry, Chief of the General Staff and Prussian reformer. Grolman joined the infantry regiment "von Möllendorf" of the Prussian Army on 1 April 1791 and advanced to the rank of second lieutenant by early April 1797. At the end of March 1804 he became premier lieutenant of the army and inspection adjutant of the Berlin infantry inspection under Field Marshal Möllendorf. He rose to the rank of Staff Captain at the end of September 1805 and was a member of the prestigious Military Society in Berlin. During the Fourth Coalition War, Grolman took part in the Battle of Auerstedt in 1806/07 and, after the defeat of the Prussian army, became adjutant to the Prince of Hohenlohe. Sent with messages to the Prussian King Frederick William III, Grolman escaped the surrender of Prenzlau and joined the army in East Prussia. He found employment on the staff of General L'Estocq's Prussian Corps. In this capacity he took part in the Battle of Preußisch Eylau on 8 February and received his promotion to Major after the Battle of Heilsberg. After the war, Grolman was a member of Scharnhorst's Military Reorganisation Commission and on 1 March 1809 became involved in the work on the reorganisation of the army as director of the first department of the War Ministry. At the same time, he thus rose to become head of the newly created military cabinet.

However, as he was determined to fight against the French occupation of Germany, he still took the opportunity in 1809 to enter Austrian service and took part in the campaign in Franconia and Saxony in the corps of General von Kienmayer. This war was not successful, however, and Grolman fled via England to the Spanish army (1810), where he served as a major and commander of a foreign battalion. He took part in the war against the French troops, but as early as January 1812 he was captured during the siege of Valencia. He escaped to Switzerland in June and then went from Bavaria to study at the University of Jena. In the spring of 1813, Grolman was reinstated as a major in the Prussian army. He served in the following campaigns as a general staff officer in various corps and took part in the most important battles of the wars of liberation at Großgörschen, Bautzen and the engagement at Haynau. After the armistice of Pläswitz, Grolman received his promotion to lieutenant colonel and a post as general staff officer with the II Army Corps. He was seriously wounded at the Battle of Kulm, but nevertheless fought as a colonel in the Battle of Leipzig and then took part in the campaign of 1814 until the Peace of Paris. In 1814 he was sent to the Congress of Vienna, but already in March 1815 he became quartermaster general of General Blücher's army. In this capacity he served in the campaign of 1815.After the war, Grolman served in the Topographical Department of the General Staff. He advanced to Major General and Chief of the General Staff (then still the 2nd Department of the War Ministry). But already in 1819 he left the army under the pressure of the restoration of the Prussian monarchy. He was not even granted a pension. He moved to the small village of Gosda (east of Cottbus). Five years later, Prince August of Prussia persuaded him to return to active service. Grolman served as a lieutenant general and commander of the 9th Division in Glogau. In 1830, at the time of the Polish Uprising, he commanded troops under Gneisenau on the Prussian border. At the end of March 1832, he was entrusted with the duties of Commanding General of the V Army Corps in Posen and was appointed Commanding General on 9 September 1835. At the same time, King Frederick William III appointed him Chief of the 6th Infantry Regiment. In 1837 he was promoted to General of the Infantry, and on the occasion of the Order's feast he became a Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle in January 1839. In 1843 Grolman died in the line of duty.

Enrique José O'Donnell y Anatar, conde de La Bisbal or (English: Henry Joseph O'Donnell) (1769 – 17 May 1834) was a Spanish general of Irish descent who fought in the Peninsular War.

Alexander Fabian Burggraf und Graf zu Dohna-Schlobitten (b. 17 November 1781 in Schlobitten; † 26 August 1850) was a Prussian lieutenant colonel and Knight of the Order Pour le Mérite. As the younger son of an aristocratic family, he initially chose a military career like many of his peers. He became an infantryman in the Schöning regiment and was second lieutenant at the outbreak of the war against France in 1806. Dohna-Schlobitten took part in the battles of the corps under the leadership of Lieutenant General Anton Wilhelm von L'Estocq in East Prussia at the end of 1806/beginning of 1807 and distinguished himself so much during the Prussian night attack on Soldau on Christmas Day 1806 that his commander L'Estocq, together with others, proposed him to the King to be awarded the Order Pour le Mérite. In L'Estocq's report of 22 February 1807, he asked "...at last to award the Order p.l.m. to the Kapitain von G. and the Lieutenant Graf von Dohna, recruited à la suite, both of whom distinguished themselves extraordinarily in the night attack on Soldau on 25 December last, by leading attacking columns and volunteers with great insight and bravery. Both were shot through the arm..." By Most High Cabinet Order of 27 February 1807, the King approved the suggested award of the Order. "My dear L'Estocq [...] I also grant the Colonel of L. [...] the Order of Merit, as well as the Captain of G. and the Lieutenant Count Dohna because of the affair at Soldau, where both distinguished themselves excellently...". In 1810 he went to Spain and remained there until 1814.

Short biography in the first instalment of this series.

Note by Moritz von Hirschfeld: ‘I once met the Duke of Neuwied, who was supposedly the source of this anecdote. I encountered him exchanging tender kisses with a pretty innkeeper’s daughter - no surprise as Neuwied was a handsome, kind man and also a Prince. I however, could not resist to ask the question if he would not have preferred a bout of delousing with a pretty Spanish girl. He immediately denied to have been the source of that anecdote, and declared it to be a defamation by the English officers who, being coarse and loud-mouthed, earned little appreciation from the Spanish but many a box round the ears by the beautiful hands of the Spanish Ladies.’

Joaquín Blake y Joyes (Vélez-Málaga, 19 August 1759 – 27 April 1827) was a Spanish officer who served with distinction in the French Revolutionary and Peninsular wars.

Pierre-Antoine, comte Dupont de l'Étang (4 July 1765 – 9 March 1840) was a French general of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, as well as a political figure of the Bourbon Restoration. Already a highly experienced divisional commander, he entered Spain in 1808 at the head of a corps made up of provisional battalions and Swiss troops pressed into French service from the Spanish Royal Army. After the occupation of Madrid, Dupont was sent with his force to subdue Andalusia. After a few initial successes he had to retire toward the passes of the Sierra Morena. Pursued and cut off by a Spanish army under the Captain General Castaños, his corps was defeated in the Battle of Bailén after his Swiss troops deserted and returned to their former allegiance.

Note from Moritz v. Hirschfeld: ‘The Spanish soldier is brave as everyone else if he is led well. Individually, the Spaniard is very brave. The army of General Custine at Bailén consisted, apart from General Reding's brigade, only of a levy or Landsturm. There were no regular Spanish troops, only the brigade of Swiss Reding, General in Spanish Services. It consisted of three battalions of Walloon and Spanish Guards, one Swiss battalion and three Spanish grenadier battalions; all 7 battalions fought very well and decided the matter. All the others, about 10,000 men, were armed peasants. The first attack was by two Landsturm battalions, where the above-mentioned story took place.

Francisco Javier Castaños y Aragorri (* 22 April 1756 in Madrid; † 24 September 1852 ibid.) was holder of the title Duke of Baylen (Duque de Bailén) from 1833, Count of Castaños y Aragones and Spanish general in the War of Independence against the French.

Luis Alejandro de Bassecourt y Dupire (Château de Heuchin, Fontaine-lès-Boulans , Calais , July 1 , 1769 – Zaragoza , January 17 , 1826 ) was a Spanish soldier of French origin, nephew of Juan Procopio Bassecourt y Bryas and captain General of Valencia He was a knight of the Order of Montesa.

André Masséna, Prince of Essling, Duke of Rivoli (born Andrea Massena; 6 May 1758 – 4 April 1817), was a French military commander during the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. He was one of the original 18 Marshals of the Empire created by Napoleon I, with the nickname l'Enfant chéri de la Victoire (the Dear Child of Victory).

![[GStA, I-HA-R15 B 283] [GStA, I-HA-R15 B 283]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!DIhU!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd0b21771-31d8-4c4e-9263-5c0710cadde3_1506x820.jpeg)

Amazing. Wonderful work.

Incredible stuff!!