DIFFERENT SKIES I. : GERHARD ‘KÜKEN’ HUBRICH

German pilots who flew combat operations in two World Wars.

In the German Luftwaffe they were known as ‘Die Eisgrauen’, the ‘ice greys’ in reference to their hair colour as well as their seniority. Their lives spanned the entire history of civil and military aviation. Many of them had begun their flying careers less than a decade after the Wright brothers inaugurated the aerial age with the world's first successful flights of a powered heavier-than-air flying machine. They had fought over the battlefields of the First World War in colourful machines made of wood and canvas, had spent the interwar years in civil aviation or actively assisted the secret development of the nucleus of the future Luftwaffe and had gone on to fly combat missions in the Second World War, now in control of powerful modern aircraft at the dawn of the jet-age. This series will tell their story.

‘Maybe I would have been killed in something like a tram accident, had aviation not become a talking point.’ - Gerhard Hubrich

GERHARD ‘KÜKEN’1 HUBRICH

Gerhard Hubrich was born in East Prussia on 30 July 1896 as one of five children and not much is known about his childhood and early youth. His autobiography, which was published in a small edition in Germany in 1969, begins in 1913 with the 18-year old Hubrich starting a mercantile apprenticeship in Berlin after having failed to enlist as a soldier due to his weak physique. Having always been keenly interested in technology and mechanics, spending many hours caring and driving his 400cc V-twin engined 1913 Wanderer motorcycle, his other passion was aviation - so whenever he could, he would not only stare at the aeroplanes performing in the sky above the aviation-dorado of Berlin-Johannisthal, but he would also mingle with pilots and mechanics. It didn’t take long until he was allowed to assist in the repair of aircraft engines, but even though he took twice-weekly evening lessons in engineering and aircraft construction, there was no way he could raise the 4000 Marks necessary to enlist himself at a flying school. To overcome this problem, Hubrich volunteered for work at the Wenskus-Flugzeugbau company in Johannisthal - a small workshop, not much different to that of a carpenter. Within the following months and under Wenskus guidance, the young Hubrich was not only allowed to conduct several solo-’flights’ (needed to pass a pilots exam), he was also introduced into the who-is-who of early German aviation which in the evenings could be found the legendary Cafe Senftleben in Johannisthal. Valuable contacts, which even allowed him to act as on-board ‘ballast’ during test-flights of the chief pilots of the Albatros and Reinhold Boehm companies.

The outbreak of war in July 1914 not only ended Hubrich’s career as an aircraft mechanic, but also his chance for a pilot’s exam. On the other hand however, all pilots, flight students, mechanics and other technical personnel were either drafted into the Fliegertruppe at Döberitz, or - as in Hubrich’s case - into the Freiwilliges Marine-Flieger-Korps in Johannisthal. A formation which consisted of personnel with technical or intellectual backgrounds and as Hubrich put it: ‘those men who claimed the monopoly on eternal freedom and who showed no understanding whatsoever of strict military discipline’, men who: ‘if they’d worn a uniform would have disgraced the entire German Army’. Yet flight training continued while the rag-tag bunch of men served as a reserve pool for the flight and technical personnel of the Imperial German Navy and thus the young engineer Hubrich was sent to the Gothaer Waggonfabrik not only to work, but also to pass his pilots exam.

MARINEFLIEGER

After receiving basic naval training on the Müggelsee in Berlin, Hubrich was transferred to the Seeflugstation List on the island of Sylt, a formation with operated seaplanes of various types. There: ‘I soon realised that my actual enemy was not the one I sought to annoy with my 5-kilo bomb. My enemy, in many diverse forms, was always with me. It was my own engine and the elements, the sky and the water, who had me and my apparatus at their mercy.’ Taking the weakly powered, primitive aircraft with their heavy swimmers and with their rudimentary instruments out over the North Sea, was a difficult and often lethal undertaking even without having to attack an enemy surface vessel, a submarine or indeed an enemy seaplane. Reconnaissance and anti-shipping patrols from Sylt continued until the end of March 1916. Hubrich wrote:

‘I got a new command to Heligoland. A new aeroplane and a new observer. In addition a new, rough and jovial circle of comrades’. His new posting was to Seeflugstation (SFS) Helgoland where crews used Friedrichshafen FF.29 seaplanes to conduct long-range naval reconnaissance flights. ‘Extended reconnaissance meant up to six hours out over open sea. There was no radio direction finding in those days and with the wind and the weather it was often pure luck to locate the little rock of Heligoland on our way back. One time I had to land next to a fish trawler to ask for the exact course while at another time, with two aircraft we curved around through night and fog without being able to find our Heimat Heligoland. I was lucky to be able to put my feet on dry land at Norderney, my wingman in the other machine, who had stayed at my side until the last moment, went missing and never returned. Another day my engine broke down while we were out over the sea, my wingman hadn’t seen me going down, which was a depressing thing as no one would know where to look for us. There surely are people who can find the words to express the feelings one has when one drifts on open sea, several 100 kilometres out, awaiting nightfall, in a contraption held together by wire, wood and canvas and sporting large wings and two plywood floats. And that with the underlying and disconcerting certainty that this operational zone would not be entered by any vessel which could bring salvation. That is a feeling impossible to put in words. A drifting ship rolls on the sea, but what a wobbling aeroplane, floating on two short pontoons pulls off is hard to describe (...) To drown - to just drown, that is the wish and the only salvation. (...) and when the wind turned and the wingtips began hitting the water threatening to sink the aircraft, I desperately scrambled through the wires, back and forth from one wing to the other, using my hundred pound weight to reduce our chances of sinking (...) Later I was a fighter pilot in Flanders where sometimes I had 2 or 3 air battles to fight per day during which each of us sprayed the other with two machine guns at distances of 50 metres and less. Participating in this sport made me feel secure (...), [I am] so happy I have gotten away from naval aviation and all the invisible dangers it involved.’

Miraculously saved by a torpedo boat Hubrich survived and it is hard to imagine that anything more dangerous than this could be experienced by anyone, yet it is the next stage in Hubrich’s career, which he later described as a ‘wahres Himmelfahrtskommando’, a true suicide operation.

FLYING EELS AND FALLING OBSERVERS

After being rotated through several Seeflugstationen in Holtenau, Warnemunde and Flensburg which specialised in trialling of torpedo tactics and the training of ‘torpedo flyers’ we find Gerhard Hubrich, now teamed up with his observer Lt.z.S.d.R Theodor ‘Tetje’ Rowehl, in II. Torpedo-Flugzeugstaffel in Zeebrugge in Belgian Flanders. On 9. September 1917 this formation conducted what would become the final German aerial torpedo attack in the western theatre of war. At 13:10 three aircraft took off from Zeebrugge, two of them Gotha WD.11 torpedo-bombers, one piloted by Flugobermaat Gerhard Hubrich to attack heavily protected convoy which had been spotted going past the Thames Estuary. 90 minutes later and using the latest attack methods (concentrating efforts on a single, chosen target), two German torpedos find their mark, one of them dropped by Hubrich: ‘(...) a few more seconds. I drop my eel which now runs on its own steam towards the steamer ‘Storm of Guernsey’, to hit it aft and to send it to the bottom later. Immediately after the drop Tetje Rowehl grabs the machine gun and - at shortest distance - takes the command bridge under fire, to stop the vessels commander to take evasive action.’ The ‘Storm of Guernsey’ (440 BRT) sank about one mile south-east of the Sunk lightship, 14 miles off Harwich.

Back in Flanders after a brief interlude in the Baltic in late November 1917 and incident happened which would see Hubrich being put under arrest and which was recorded in the formations war diary: ‘10:50 to 11:10: training flight, Hubrich and Rowehl on Brand C. S/N 1015. During the flight Lt. Rowehl fell from the aircraft and was badly injured. He was transported to the hospital in Bruges.’ An official inquiry came to the result that Hubrich had acted irresponsibly by prohibited and dangerous maneuvering. Hubrich himself wrote later: ‘Christiansen, the leader of the reconnaissance formations had received new aircraft types. Small, manoeuvrable biplanes, nicknamed ‘Camels’ and made by Hansa-Brandenburg’ [Hansa-Brandenburg W.12 ‘1015’ was the second prototype of the W.12 series which later received the service designation Hansa-Brandenburg C3MG] ‘I hadn’t flown small kites like this for quite some time and I was tempted to see what one could do with them (...) While I shuffled myself into the seat my yokemate Theo Rowehl came around wanting to fly with me. ‘Very well’ I say, ‘but strap yourself down’ (what usually wasn’t done in a seaplane to be able to free oneself quickly in case of a crash landing.) The machine, which was very responsive, found my approval as one could do all kinds of nonsense with it. In a particular situation I suddenly find myself outside the seat, but manage to hold the steering wheel and to pull myself back on the seat. Then I see a pillar of water below me (...) I turn over to Tetje Rowehl (...) - his seat is empty - For Christ’s sake! Should the pillar of water have been created by him? It was! At that moment of realisation he appeared back at the surface. Arms, head and legs hanging down limp, he didn’t move (...) He had gone overboard from a height of about 70 metres (...) It didn’t look good for him.’ Although badly injured, Rowehl survived the terrible fall. He would become a highly decorated airman of the Luftwaffe during the Second World War. It is unclear how far Hubrich, who seems to have fallen victim to reckless, boyish enthusiasm, was held responsible for the incident. What is sure is that soon after he was transferred to the fighter arm.

‘KÜKEN’

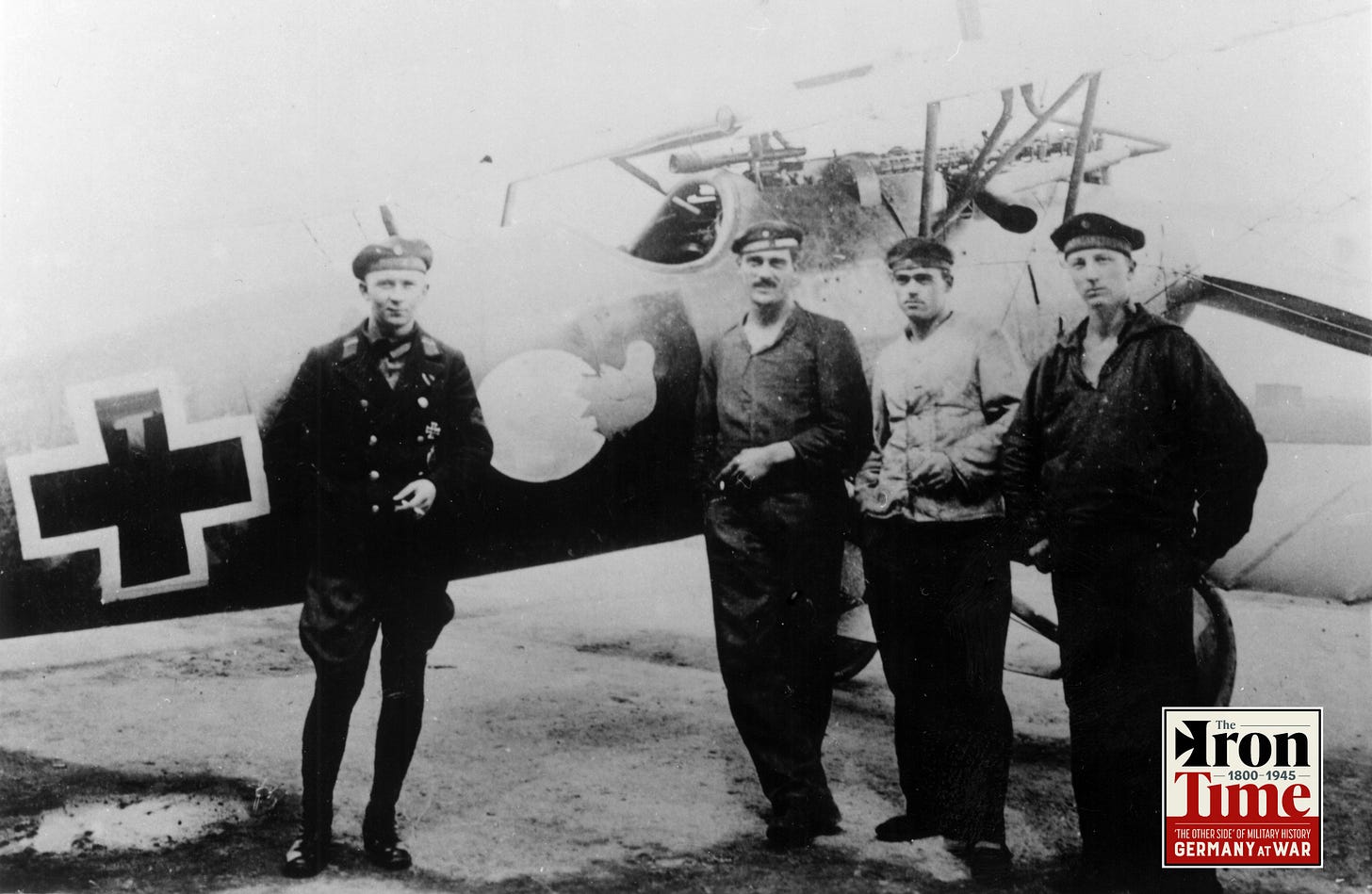

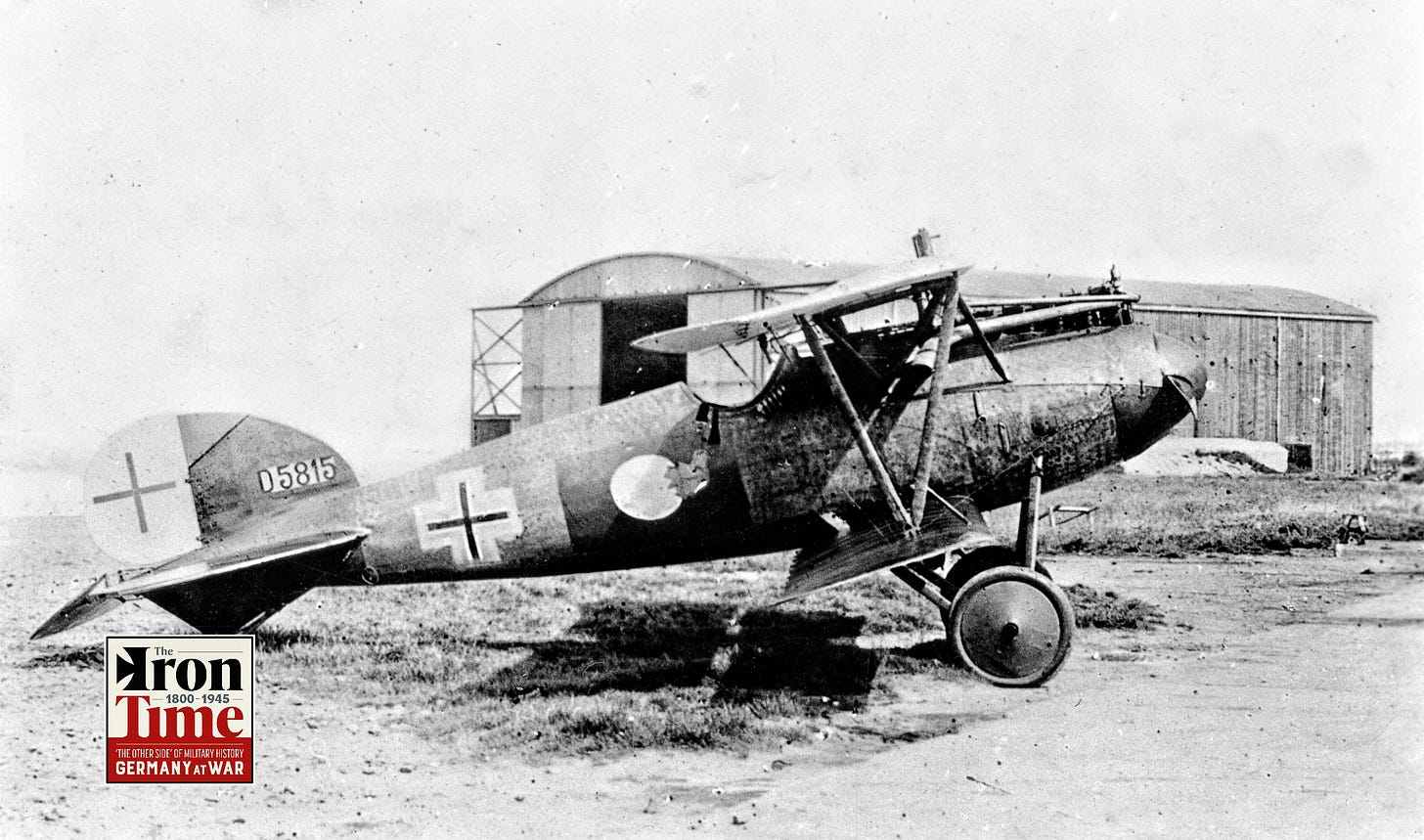

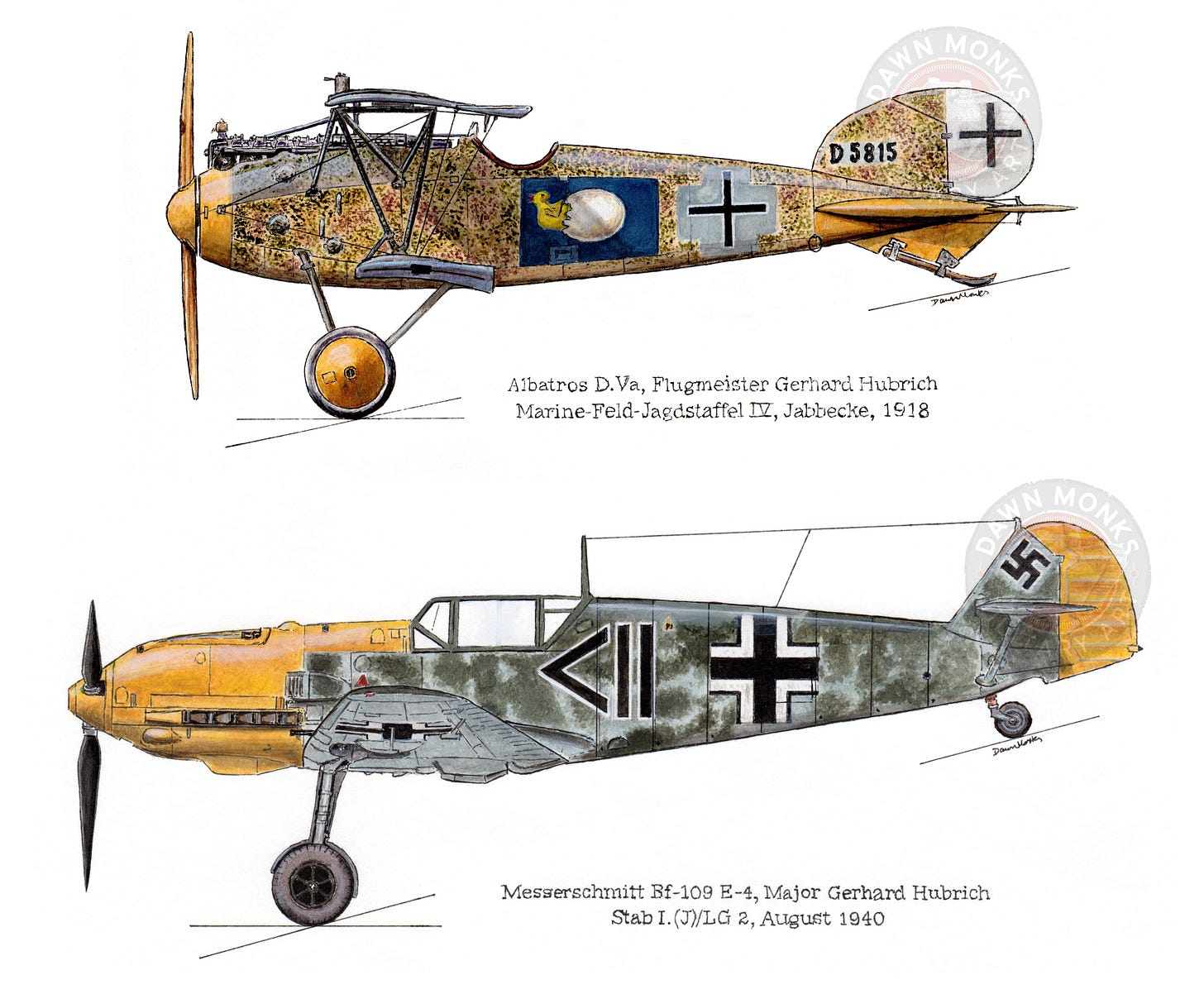

On 5 May 1918 the war diary of the Seefrontstaffel (Seefrosta) noted that: ‘As our torpedo boats didn’t require protection, 4 aircraft (Lt. Spies, Poss, Cranz and Flugobermaat Hubrich) conducted a free-hunt and reconnaissance flight over the sea from 18:05 to 19:50. (...) at 19:10 a squadron of 6 enemy Sopwith seaplanes was encountered and successfully attacked in [square] 50 on an altitude of about 1000 metres. During the course of the battle 4 enemy aircraft were shot down or forced to land.’ - of the four, one was confirmed as Hubrich’s first aerial victory: ‘His incendiary and tracer rounds just missed my machine by a few metres. Acting on instinct I pulled the throttle back and turned towards him. Under the risk of increasing the chances of the foe on my right, I flew a steep left turn, firing all the time, forcing the foe on my left to fly through the shower before I dove downwards. My foe did the same (...) spinning downward inexorably until plunging into the water close to the coast’. At this time Hubrich’s aircraft was already sporting his quite unique insignia: ‘On our machines we all had our own identification symbol, so we know who is sitting in the other machine. Already at the beginning of my flying career I had dragged the nickname Küken (chick) around with me under which I am still well known now that I am 70 years old. Here, with the fighter force the mechanics, much to my surprise, had brushed a large, white and cracked-open egg from which hatched a yellow chick with a red beak, onto both sides of my aircraft’s fuselage. It had officially become the Kükenmaschine (lit: chick-machine) which looked quite amusing.’ On 17 September 1918, now flying with Marine-Feld-Jagdstaffel IV, Hubrich scored his 5th victory over a Sopwith Camel (F3931) of 210 Squadron. The man who made Hubrich an ace was 2nd Lt John Edward Harrison from Newcastle, who died in hospital after having been rescued from the wreck of his machine by German infantry. Hubrich would go on to score a total of 12 aerial victories during the First World War.

There is no space here to illuminate the quite incredible inter-war period adventures of ‘Chick’ Hubrich. His life’s journey would see him as a passenger pilot in 1919/20 before we find him conducting slightly more shady, but doubtlessly financially worthwhile deals, ‘organising’ former German military aircraft and selling them to several Scandinavian governments and during which he met none other than Hermann Göring who tried in vain to sell a Fokker D.VIII on the Amager airfield. A career in civil aviation, as technical advisor in Norway and several other roles linked to aviation followed. By 1936 we find him in the new Luftwaffe in the rank of Major and as chief test pilot in the Weserflug AG, a role to which he would return now and again throughout the war, and one which allowed him to gather great amounts of experience flying Weserflug licence-builds of most Junkers, Messerschmitt and Focke-Wulf aircraft.

DIFFERENT SKIES

Not a lot is known about his exact career during the Second World War, not even when he rejoined the Luftwaffe. His own memoirs - written nearly 25 years afterwards, is confusing at best - just a wild construct of anecdotes and reminiscences often cobbled together without context and in the worst case with the wrong dates. What is clear however, is that Hubrich seems to have enjoyed a peculiar kind of freedom, which suggests that he wasn’t just a regular Major in the Luftwaffe. According his own words, he flew briefly with I. Gruppe of Jagdgeschwader 26 (under command of Major Gotthard Handrick), before being transferred north to join 10. (Nacht)./Jagdgeschwader 26 (Oblt. Johannes Steinhoff) in Jever, which had just taken part in what became known as the Battle of Heligoland Bight, the first "named" air battle of the war. Transferred to the staff Jagdgeschwader 1 under Oberstleutnant Carl Schumacher, Hubrich participated in the Battle of the Netherlands, flying ground attack missions on the Dutch airfields of Bergen aan Zee and Alkmaar, as well as on Dutch troop concentrations at Den Helder. Later we find him securing and evaluating airworthy Dutch Fokker aircraft on the island of Texel. As JG1 did not follow the armies in the invasion of France or the Battle of Britain, instead being kept back on the coast, Hubrich requested leave to: ‘to be able fly further missions towards Dunkirk with some amicable commanders of other squadrons’.

During the following weeks we briefly find Hubrich in charge of an experimental unit trialling low level bomb attack methods with Bf 109 and Bf 110 fighter bombers. On 22 August we see him flying operational missions with the Stab of Lehrgeschwader 2, where on 24 August 1940, he claimed his one and only aerial victory: ‘on the way back from Maidstone we are suddenly pounced upon shortly before reaching Folkestone. Relentless screaming from the earpeace ‘Spitfire, Spitfire, Spitfire on the right, Spitfire on the left, from above, behind you’. Like held-down corks bob out of the surface of the water when released, English fighters suddenly emerged from a bank of clouds beneath and shortly afterward a Spitfire came from the side and began to take a 109 in front of me under fire. There was no immediate threat for myself so I could line it up in my sights. As it left my sights the whole tailplane section had been shot off it. (...) suddenly a blow on my control column and then a row of holes appears in my right wing (...) Several centimetres above my head the whole length of my canopy had been ripped open and some parts of it had been blown into my collar.’ Hubrich managed to land his battered 109 safely at Marck, where in addition to hits in the fuselage and wing he found the elevator rod sported a thumb-sized hole.2

In the spring of 1941 Hubrich, still formally attached to the Weserflug AG ended up in Italy where he oversaw the reassembly of Ju-87s and Me-109s shipped to the southern theatre of war. Hopping back and forth from Germany to Italy he also continued to conduct test-flights for the company, before ultimately moving to Germany in 1942. At the Weserflug in Lemwerder he flew and trialed the latest versions of the Focke-Wulf 190 including super-charged high-altitude interceptor variants and also Junkers bombers and night-fighters of all kinds - including a Junkers Ju-88 P-5, an anti-tank and bomber destroyer variant armed with a single 88mm anti-tank gun. So far it was unclear if an example of the P-5 had ever been built, Hubrich’s memories leave no doubt that at least one model existed : ‘our factory in Lemwerder had been ordered to mount am 8,8 cm cannon into a Junkers Ju-88 (...) When altitude and direction were correct, I pressed the trigger (...) this went along with an enormous crash and a mighty shockwave went through the whole aircraft. All electrics ceased to work, the engine cover of the starboard engine was blown off while at the same time prolonged vibrations in the whole aircraft became so bad that I feared the engines would break from their housings. I had to throttle the engines back so far that I could just hold us up in the air. The floor hatch cover had fallen off and it was only luck that my grease monkey had stayed inside the machine. There was no way we could have fired a second round (...). After this trial built modifications were made and reinforcements added, but I have never learned if that model was ever used.’

Hubrich summarizes the final years of the war thus: ‘We built a helicopter. Hitler Youth was trained to ram fighter aircraft into bombers and on Hitler’s orders we were supposed to blow up our factory. We didn’t do it. The Americans stood close to Bremen. A low-flying American fighter fired his machine guns into my garden in which my wife stood with my son in a pram. A shell detonated in front of my house and smashed my windows and furniture to bits. The war was over.’

Gerhard ‘Küken’ Hubrich died in Bremen on 20 October 1972

Special thanks to Gregory von Wyngarden

‘chick’

It is highly likely that Hubrich was indeed hit by friendly fire.

Those early planes were amazing. The men who flew them, more so! Some really interesting history in this account.