Not much has been written about Germany’s U-Boat arm in the First World War. Stories of crews and commanders of his Imperial Majesty's Navy were told during the interwar period ,where their biographies formed part of the enormous flood of war literature so popular during the time. But the exploits of Germany’s first submariners were soon overshadowed by the propaganda-fuelled popularity of their Kriegsmarine successors in the Second World War. The stories of the Kaiser’s pioneering ‘Grey Wolves’ quickly disappeared from public memory, the published biographies banished to dusty shelves. It is a great stroke of luck that only recently, two so-far unknown, private patrol diaries have come to light in Germany. Written by Oberleutnant zur See Hans Kawelmacher, who at the time served as 1st Officer on SM ‘U-80’, a German Type UE I mine-laying submarine.

U-BOAT THREAT

Deceit and cunning are not necessarily sympathetical characteristics, but in wartime they become invaluable. During the First World War, Germany pursued a highly effective U-boat campaign against merchant shipping, intensified over the years and almost succeeded in bringing Britain to its knees in 1917. Shortly after the outbreak of the conflict in August 1914, the romantic codes of honour so many naval officers had committed themselves to, disintegrated in the face of the reality of war. It didn’t take long until the time-honoured Cruiser rules1, which in their essence defined that an unarmed vessel should not be attacked without warning, literally went overboard. German U-Boats could stalk and finish-off their prey unseen, launching their lethal torpedoes from the cover the dark depths of the sea. One of the first and most noteworthy blows was struck by SM ‘U-9’ under Kapitänleutnant Otto Weddigen on 22 September 1914. While on patrol through the Broad Fourteens, in the southern North Sea, ‘U-9’ encountered a squadron of three British armoured cruisers of the Cressy-class; HMS ‘Aboukir’, HMS ‘Hogue’, and HMS ‘Cressy’, obsolete vessels which formed the sardonically nicknamed ‘Live Bait Squadron’, assigned to prevent German vessels from entering the English Channel from the eastern end. ‘U-9’ fired four torpedoes, reloading while submerged - a rare and dangerous feat at the time - and sank all three in less than an hour. 1,459 British sailors perished. The submarine, which the British Admiralty had considered mere toys, had proven its lethal value and a single German U-Boat in the right hands could pose a considerable threat. SM ‘U-35’, under command of Lothar Von Arnauld De La Periere, sank a total 193 vessels amounting to a total of 453,369 GRT.

MINENLEGER

There was however, a different class of U-Boat, one which wasn’t primarily designed to attack its prey directly, but by stealthily deploying a weapon which could have an effect days, weeks or even months later. This was the speciality of Germany’s mine-laying U-Boats. Both anchor and floating mines had been in existence before the outbreak of war, yet their first mass-deployment began in the autumn of 1914 when both British and German mine layers attempted to block important sea passages with minefields. Mines were also used to secure the approaches to one’s own harbours. The German Imperial Fleet protected the Jade Estuary, the entry to Wilhelmshaven, their most important North Sea Base, with a screen of anchor mines. Any surprise attack through a minefield was equal to suicide, but placing one’s mines into the enemy’s waters, shipping routes and well guarded harbours, like Portsmouth and Scapa Flow in particular, was an even more lethal task - at least for a surface vessel! A U-Boat could perform such a task with a far greater chance of success.

In the middle of November 1914 the German Navy ordered the construction of submersible mine-layers of the UC-Class. They were small and could carry 12 mines. As these were rather cost ineffective, the German Seekriegsleitung [Naval Warfare Command] ordered a 10 larger, upgraded underwater minelayers of the so-called UE-Class. These were delivered between the end of 1915 and June 1916. The UE boats could carry 34 mines, enough to create highly dangerous mine barriers in or in front of enemy harbours or other busy shipping lanes. Even though the boats of the UE class had terrible sailing qualities and design faults, they sank 125 civilian and 8 warships, making them one of the most effective weapon systems in Germany’s U-Boat fleet. During the First World War the 375 commissioned U-Boats of the Imperial German Navy sank 5554 merchant ships, a total 12.191.996 BRT. 187 German U-Boats were lost, taking more than 5000 German sailors down with them.

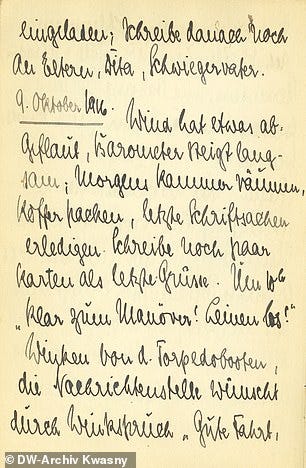

The recently rediscovered patrol diaries of Oblt.z.S. Kawelmacher offer a unique and fascinating insight into the life and hair-raising tension on board one of his Imperial Majesty’s minelayer U-Boats in the daily fight against the unforgiving sea, the elements, fledgling technology and - only at the last instance - the enemy and his shipping. What follows, are the surviving diaries outlining U-80s second, third and fourth patrol, between 3 October 1916 and 17 March 1917. Transcription and translation have (as usual) been done by me. Thanks to Mr A. Kwasny for granting me exclusive access to the original manuscripts.2

SM U80, SECOND WAR PATROL: 3 OCTOBER TO 11 NOVEMBER 1916

3 October 1916: Return from leave at 8 in the morning, arrival in Wilhelmshaven. Drove to boat in the dockyard. 12 pm taking over mines, came past [SMS]‘König Albert’ which is lying in the dock. Conducted a short dive. 7 pm evening into the city to run some errands. Then dinner in the casino and briefly visited Ernst

4 October 1916: Before midday at 11 am ready to sail! Packed suitcases, vacated my room, cleared the notebooks; lots to do because Schliemann left a lot undone during my absence. When putting to sea we go past ‘König Albert’. Lots of semaphore messages, from the commander in particular.

Ernst Jäger sails past, proud in the A-Boat. I call over to him, waving. Wedel sails into the lock with us. I have the watch. Already bad weather outside, barometer reading falls quite severely. Shortly before 7 pm arrive in Heligoland. The flotilla boat has brought the mail. Only one letter from Dita!

5 October 1916: Writing letters until 10 am, then on board to do some paperwork. 1:30 pm ready to sail, moving out to dive! Heavy sea outside, depth control less than 2 metres down is virtually impossible. Flotilla commander on board with us. Entering harbour at 4:30 pm. In the evening guest in the mess, writing letters afterwards

6 October 1916: Weather is getting worse and worse. Sea state 9. Mid-morning we head out for a trial dive. The boat is getting very stern-heavy. At 40 metres depth 5 tons of water enter the aft compensation tank! New vent in the mine tube drain valves is leaking! Departure is postponed. Work continues day and night! Reason for depth control the problem lies in the leakage.

7 October 1916: Weather remains unchanged! Commander’s birthday today. We congratulate and present him with a wonderful crystal carafe. The helmsman has booked four musicians; morning serenade. Vent is now leaking in a different place! At 4 in the evening, despite the bad weather, the mail steamer arrives - but without any mail for U-80! I am very disappointed, I have been looking forward to a letter from Dita! Evening in the casino. A musical evening. Schliemann and I are Invited by Kapitänleutnant Helinger; nailing3 the ‘Roland of Heligoland’ with an ‘U-80’. Back home at 2:30 in the morning: cold, rain! I have a bad cold!

8 October 1916: Schliemann and I sleep until 10:30 am; Oberleutnant von Schrader, Oberleutnant Hermann and Stabsarzt Lachmund wake us. The weather is still bad. Wind force 10, sea state 9 and rain! The engine room personnel are working day and night on our leak. The eagerly awaited mail steamer brings a single letter for U-80, it is for me, an express letter from Dita! How happy I am. In the evening the commander invites Schliemann, Hundt and me to a hot punch. Afterwards I write to my parents, Dita and father in law.

9 October 1916: Wind has calmed down a little, the barometer slowly rising. Vacate my chamber, pack my suitcase, do some final paperwork and write a few postcards.At 10 am: ‘Man the lines, ready to cast off!’ Signalling from the torpedo boats, the signalling station wishes ‘Good journey, much success and a happy return!’ by a semaphore message. Then we are outside the jetty and the boat enters the strong swell. Hazy weather, a single ray of sunlight illuminates a small piece of the red rock face and is gliding a few little houses standing on the upland. Then we all get into the boat for a trial dive. We go down to 40m to test our boat. All seemingly leakproof! Course set towards Amrum. The real force of the sea is only hitting us when we leave the lee of Heligoland. Half of the crew is seasick! Up on the conning tower one is getting soaked by the cold waves crashing down on us! In the evening we are overtaken by two German torpedo boats. We fly the identification signal. There is a fish trawler too. We release it at nightfall. I have the watch from 8-12pm. Wyl and Gar-Dip lightship passed at about 11pm, lights of Esbjerg are visible.

10 October 1916: In the morning we are near Corns Riff lightship, an infamous area where English U-Boats like to lie in ambush and in which numerous floating mines have been reported. We pass through without incident. At 10am we leave bonus number VII and send a radio message to ‘Arkona’. Weather is getting worse. The Sea grows more violent. Only one sailing ship and a large, suspicious steamer in sight - we stay surfaced and evade both. During my watch, between 6am and 8am, the sea is getting so rough that the boat is unable to stay on course. Thus we dive to 35m depth. Boat still lurching about heavily! Slowly the hunger is making itself felt; most of us haven’t eaten for two days. My fever and the cold are gone. I quickly scoff something down. After that depth control watch between 2 and 4 at night.

11 October 1916: Slept for two hours, then surfaced at 6am! When opening the conning tower hatch the barometer reading makes a big jump - toward the bottom. Again no weather improvement.For several minutes the boat is getting buried by the sea, only with effort we get out again! Weather much worse than on the first patrol. 12:30, I have the watch and get strapped into place up above. Conning tower hatch is being flipped down. At about 1:30, a heavy sea coming from astern, I cling to the mine deflector strut. Boat is keeling over, I am sure we have capsized already, as it is righting itself anymore! I can’t breathe and above me there is nothing but a green mass of water. Then suddenly the boat rights itself - the pace next to me, where Bootsmannsmaat Hüter has been strapped into position, is empty. The conning tower hatch has been ripped open by the sea and a huge amount of water has washed into the boat; I look towards the portside, Hüter is floating in the water and I manage to pull him in before the next sea crashes down. As the boat is too exposed on the surface, the commander gives the order to dive at about 2pm “Alarm! Flood the tanks!” Schliemann has taken over my place at the depth control station because I am too wet, I am told to change. Boat goes down to 20 metres and suddenly falls to 40 metres, going down by the stern. Something is wrong! ‘Compressed air’ to get up again, and it works; a vent has been operated the wrong way and by doing so the frontal trim tank has been emptied - everything had been pumped astern! Repairs and trimming take 1 hour during which the boat hangs at the surface between 9 and 10 metres in heavy seas, not being able to surface or dive! If one comes into sight now, that is the end of ‘U-80’! It’s all working out; I relieve Schliemann, we try to dive. I level the boat at 30 metres, it is still rolling slightly. The watch below can ‘rest’, the watch can tidy the boat. I am relieved at 4pm, read Dita’s letters - happy again and quickly forget about the weather and the technical glitches.

12 October 1916: We surface at midnight. The barometer jumps upwards by 9 mm, and the storm is obviously on the wane. The commander decides to continue the journey above water and to recharge the battery and compressed air. Now and then there are still some impressive splashes going over. Schliemann is taking the watch, I go to sleep, which I manage to do quite well even though the boat is still rolling. At 8am during my watch the barometer reading drops rapidly, squalls of rain so dense that one can hardly see 300 metres, and violent gusts of storm. After an hour the familiar wave crests start rising up, this time from the portside athwartship. Boat is keeling over up to 34 degrees! At times it makes one think it will never right itself again. We are carried off toward starboard, the course is 320 degrees! Can’t be far away from the Norwegian coast.

7 pm near Utsvie, 20 nautical miles off course. I am in luck again as at 6 pm, the time when my watch would have started, the boat has submerged as the machine personnel could not have repaired our oil engine, which has broken down 7 hours ago, at the surface - a bearing is leaking. During my middle watch the boat is still rolling 2 degrees to each side. Weather will be quite nice up there!

13 October 1916: We only surface at 3 am, because the boat has rolled up to 18 degrees during the night. The weather has calmed down a lot and the storm has passed over. At 8pm, when I have the watch and it is getting rough again, barometer reading remains in place. Heavy thunderstorms on the starboard stern quarter, air is cooling down rapidly and the sky ahead has an eerie glowing colour, yellow and green flashes above the dark clouds. Looks like a lot of wind.

And only an hour later that wind is blowing so heavily that enormous waves come crashing down over the conning tower. Both the water and the air are cold as ice - the longest watch I have been on so far! But as quickly as the storm arrived, it passes over, only the freezing cold remains, and there is such a draft in the boat that none of us is able to sleep! At 4:30 am I slip into thick wool clothing - the others hadn’t even taken theirs off - now it is bearable, I sleep until 7 am, then woken by the watch.

14 October 1916: Barometer rose by 11 mm, smooth sea with low swell. Not even a drop of water falling on the conning tower. Really odd weather! A glorious oat soup for lunch, donated by the commander; never before have I enjoyed my food so much! Listening in to Norwegian and English radio telegraph traffic, English destroyers. I try to decipher it, but we are missing some groups. Since 10 October we haven’t seen a single vessel, and we are on the main steamer line Norway - England! We are currently north of Bergen. Then during the course of one and three-quarters of an hour the barometer drops rapidly, from Z-61 to Z-34 !! Seems we’ll have to dive again tonight.

9 pm: I'm really in luck when it comes to my watch! Was just in the process of slipping into bad weather gear when the commander gave the order to dive. It was about time, the sea had already blown the conning tower hatch open, huge amounts of water into the boat. Twice it was slammed shut tightly - while the oil engines were running!! That created such an underpressure before the engines could be switched off and the hatch could not be opened anymore! Regulate air balance via relief cock and add compressed air! A horrible feeling, as if one's lungs are chasing the last breath of air. Ordered to dive to 30 metres.

We are being compensated for the shock we endured with fried potatoes - fried for the first time ‘under water’ - the entire boat was fragrant with the smell. In addition Mehlhorn, the pearl, has prepared a delicious semolina soup! In addition there is the calming knowledge that this kind of weather can’t last forever and can’t get any worse either! Someone has conjured up the gramophone which had been tied down somewhere during the storm.

15 October 1916: At 4 am we surface! Barometer dropping even further. When the boat has been ventilated a little we dive again. Sea is in such a state that the boat is being inundated with water and no human can survive up there. I have the middle watch and after that can’t find any sleep in the bad air; one can’t breathe properly. At 11 am another attempt to surface, replenish the air supply and down again! The storm is at its peak now! With the sea in that state, surfacing and diving are now very risky - but one has to go down; the feeling of utter helplessness is the worst! Mood in the boat is at an all time low. Being an officer I have to put on a brave face, but I am concerned too. We are still at 30 metres depth as due to the leaking compensation tank we can’t go any deeper. The boat is rolling and pitching so badly that half of the crew is feeling unwell, one can’t put anything on the table or lie on the berth. The boat is being thrown from one side to the other. And then I am worried about Dita! So far during this war I was always carefree and unconcerned and now that I have found happiness I want to grasp it and never let it go. If I will ever see her again? If only there was fresh air and sunshine, that would get rid of the gloomy thoughts.

6 am, off the Shetlands. Soon we can change course. If the weather had been fairly reasonable weather we could already have completed our task and be on the return journey around Ireland. We surface at 7am and again the weather is so bad that we have to go down again, without having been able to charge our battery! The watch, although well strapped down, has been washed overboard. Boat close to capsizing! The air is not good, but there is nothing we can do. Down below we roll and pitch up to 18 degrees, but due to the leaking compensation tank we can’t go deeper than 35 metres.

16 October 1916: 7 am: ‘Surface the boat!’. Battery is fairly empty, and compressed air is low too. The ballast tanks are still being pumped out when suddenly ‘ALARM!’. 3000 metres in front of a large, armed, English patrol steamer, so far unnoticed in the heavy sea. We need to dive, steamer is coming closer; the weather is our saviour. The Englishman can’t turn quickly enough and neither can he man his guns, in addition we both, in turn, disappear in the huge wave crests. We are not going downwards and flood both regulating tanks. Finally the manometer rises, we are going down - but now way too fast! ‘Stand by to pump!’ - ‘Pump!’ - The main drain pump fails! The large amount of water which has entered the boat has caused a short circuit. We open the intermediate vents and put compressed air onto the tanks - at 58 metres the boat stops falling and finally begins to rise. That was about time: the boat is designed for 50 metres, any deeper and the water pressure squeezes it together. Still submerged and at lowest speed we try to get away, the sounds of the screw propellers above are fading away.

After one hour we surface because the battery only has on 1 ½ hours of power left. There! - patrol steamer 1000 metres away! Turns towards us again, we have to go down - for the final time. All lights out except for three electric bulbs, all auxiliary circuits, even the gyro compass, switched off. Diving planes and rudder into standby mode, food preparation in the galley stopped - we have to get as far away from the Englishman as possible. In a heavy sea like this we are powerless on the surface, can’t man a gun and can only run on one course before the gail.

The air is terrible! At 10 am the Engineer reports: ‘Battery is empty!’ We have to surface! Shells in position, gun crew ready! We will probably be washed overboard, but maybe we can save the rest of the crew and the boat that way. I, being an artillery officer, rush up first together with the helmsman - nothing to be seen of the English patrol steamer. Either way we have to charge the battery, I am strapped into position on deck and have the watch. Then suddenly the rudder blocks ‘hard-a-starboard’, the boat turns twice in a circle, abeam of the sea without capsizing. Waves tall as houses crash down over the boat, we are clinging on for dear life, no time for any thoughts, only wishing to have enough air when the next one comes down on us. I really thought it was all over for me - and then the rudder started working again. We can hold our course.

Relieved at 12:30. I am so cold I can hardly move a limb, hail, gusts of snow and freezing water. At 8 in the evening the wind calms down. Barometer rising, enormous swell, but our brave boat climbs up and comes down indefatigably. Battery is charged, compressed air replenished, boat thoroughly ventilated. Then on the middle watch I spot the first star in days and pass it a greeting for my loved ones at home. This time I sleep tremendously well.

17 October 1916: 6 am: “Alarm!”. In front of us, four points to starboard, a large steamer, listing heavily. Not a single man in sight on the bridge or on deck, no insignia, no flag. Just in time, before they can have noticed us, we dive to periscope depth. The steamer is rolling heavily in the waveless swell. It has got one funnel, two masts and on deck there are several suspicious wooden crates which could hide guns. We come closer and suddenly see white smoke rising at a cargo winch on the middle deck. Not abandoned! U-Boat trap! We sail away under water. Torpedo is too valuable for that one. When we surface there is a sunny sky above, change course to 270 degrees, then to 232,5 degrees around the Shetlands. Sailing easy now, the wind is calming down, temperature above is now 5 degrees. Boat is surrounded by whales spouting large pillars of water.

Night is ice-cold again, freezing gusts and one is being soaked through! At around 8:30 a wonderful meteor was in the north, bright as day! Its tail is still visible in the sky as a fiery line for several minutes afterwards!

18 October 1916: Weather better again. In the morning we meet a steamer sailing to the Shetlands and evade above water. Shortly afterwards an armed patrol steamer hidden in squalls of rain is heading towards us, we dive. Seems not to have seen us. It’s getting colder again, the wind is freshening, just like yesterday evening.

Strong English radiotelegraphy traffic! This time the bad weather has passed us by. Wind blowing west, but remains at force 5. A strong Atlantic swell during the middle watch, boat relentlessly climbing up and down. A large America steamer illuminated by numerous lights is sailing past on the horizon.

19 October 1916: Wind blowing south, freshening up further. According to the pilot book there are mostly strong, southerly storms here near Ireland. In the evening wind force 8-9 already, sea state 8. Watch is being strapped down!

20 October 1916: Southern storm! One wave after the other crashes over the boat, throws the watch into some corner, only saved by the double belts. But we can’t dive as otherwise we’d never get out of this storm. During the night I have the middle watch. I will probably never forget it, one can’t see the waves coming in, it is pitch dark except for the glowing seas around the boat. Being thrown around by the waves so hard that all bones are bruised. Cursing, one gets up again and clings to the mine deflector strut before the next wave crashes down. Visibility 50m max., hailstorm, the saltwater burning in the eyes. I have no idea how I manage to retain this feeling of being secure, that nothing can happen to me. It is a miracle if one isn’t washed overboard.

22 October 1916: 2:07 pm Oberleutnant Schliemann is swept overboard! Both strap supports are broken. A terrible wave coming in from astern. We kept looking for him until 3:30 pm and then dived to 27 metres. The commander had spotted him briefly, floating aftwards, about 60 metres out in his bad weather gear and waving to us. The commander waved back to confirm that he had been seen, but while the boat was still turning, Schliemann had disappeared. The poor, dear fellow - Ich hatt’ einen Kameraden…

Two times yesterday, on 21.X.1916, we ran into English patrol vessels, even though we are 100 nautical miles off the Irish coast. One has spotted and reported us. Heavy radiotelegraphy traffic. We intercept a message of the English Admiralty, warning the English shipping about our presence. One U-Boat has been sighted in the Bristol Canal, another (our boat), with our exact position and course and a third U-Boat with a location we are unable to identify. Who knows, maybe Schliemann’s fate is better than what we are facing.

9:30 pm: I still can’t believe it, I just thought that Schliemann must be on watch because he isn’t in the mess with us. We are still at 30 metres depth. His poor parents! It will be weeks until they’ll learn about their son's death. And if it had been my watch, then that fate would have been mine, standing in the same spot, secured by the same straps. My parents and Dita expect me to return. I can’t believe that Schliemann is gone, and I don’t want to think about it.

23. October 1916: We surface at midnight to replenish the air and expect the sea to be in the same state. ‘Open conning tower hatch!’ - the wind is dead calm, as is the sea, only minimal swell! It is entirely incomprehensible! The sea has claimed a sacrifice and is finally leaving us in peace. We continue our journey at the surface with both oil-engines at full steam, course 170 degrees, changing to 140 degrees before midday at 11:30. Wind and little swell, heavy rainfall.

At 12:00 o’clock a sailing ship comes into sight at starboard. Shortly afterwards, close to it, a cloud of smoke - we keep our distance. On the larboard side another cloud of smoke, closing in fast. Mastheads and one or two funnels are visible. ‘Alarm! Dive!’ - we are going down on periscope depth. It’s an English auxiliary cruiser, painted blue-grey. Sadly we must not sink it, otherwise we won’t get rid of our mines. We surfaced at 4:15; 3000 metres ahead, another auxiliary cruiser with many guns which we first didn’t notice because of the swell. Turn away and dive. 5:00 o’clock we surface! Nothing in sight- we clear the torpedo tubes, pump out the diving tanks, switch on both oil-engines and continue the journey. Wonderful sunshine, minimal swell, the first nice day since we embarked on the patrol!

24 October 1916: The south-coast of Ireland! Since 10 am a fierce wind from the south-east, rough sea. Intercept enemy radio message reporting a German U-Boat near St.Kilda - probably U-75 -, another one, of the Flanders Flotilla, at Bloody Head and a third near us, probably U-63, in front of the Bristol Canal. So we haven’t been spotted after all! Probably because we were positioned in the sun! The fact that the auxiliary cruiser steamed towards us was purely accidental. Sailing the whole night and the entire day on the steamer route to Small Falls. Nothing in sight! Weather is getting worse and worse. At 9pm the barometer dropped from 754 to 738! Up above the watch is being strapped into position. At 9:30 we dive to 30 metres. Breakthrough through St.George’s Channel postponed until tomorrow evening.

25. October 1916: Surface at 6:30 in the morning, still dark above. But there, heading directly towards us with the bow pointing towards our boat, a large America steamer! We dive to 25 metres, and the steamer passes over us. 8:30, surface a second time but have to go down immediately as we came up amidst a large fishing flotilla with cast out nets. We manage to get clear, but have little electricity in the battery and can’t surface because of the danger of being seen! Lunch has been cancelled, all lights except a couple of bulbs switched off. Crew is ordered to go to sleep to save valuable oxygen.

1:00 pm - we surface: two steamers, one sailing ship visible in the far distance. Diving tanks are pumped out and so on. Turned boat 3 points against the sea. Only possible course for us. 300 degrees, we are moving away from our objective. There is glorious sunshine however, excellent weather….on land at least! At 6 pm we have to dive due to the state of the sea.

26 October 1916: Surface at 2 am. Strong swell, but no violent sea above. Lots of lights all around, but a dark, clear night. We stay surfaced. Both engines switched on, course 50 degrees, entry into St.George’s Channel! At dawn, at about 5:30 am, we spot an English light cruiser ahead of us on the same course, zig-zagging and at high-speed. We follow. Several lights of steamers on the starboard and port side. At 6:30 the cruiser turns around and is coming straight towards us. We have to dive fast and go on depth within a few seconds. There is no way the cruiser can have spotted us, maybe our bow wave has made him suspicious. Standing at the entry of the Channel and current is pushing us out again. At 8:30 we rise to periscope depth. A steamer on the starboard side, course east-west, in front of us one who looks like a escort, behind us a sailing ship going the other way.

We dive to 30 metres, dead slow ahead. Half an hour later screw noise. Coming close and passing right over us. Getting quieter towards the port quarter, disappears - that was the escort! He would be pretty miffed if he knew that there was a German ‘submarine pirate’ right below him and he didn’t even drop a water bomb! - Could have earned 20.000 Marks!

At 10 am we are on periscope depth again, 3 steamers are in sight, 2 escorts behind us; 1 fish trawler with two guns and one big, grey box with a war ensign - auxiliary cruiser, not moving. Seems we haven broken through the guard screen. Now against the current, hopefully not pushing us back into the foe.

12:30, periscope depth. Steamers all around; we dive.

2 pm: Surface! Quick look through the periscope. On the portside an armed fish trawler with tall radio masts. Top edge of the bridge and funnels above the horizon line. An unpleasant visitor! In front of us a steamer on the same course, further towards starboard is another one. We surface, pump out the diving tanks. I have the watch above, together with the commander, helmsman and pilot, each watching one side. Charging the battery, replenishing air supply. Such beautiful weather, delicious air, the sea smooth as glass! We are already at the end of the first third of the channel. Suddenly the pilot spots a large airship below the clouds on the starboard side - still quite far away, but it may have spotted us!! It is coming closer quickly. ‘Alarm!’, we dive to 30 metres. How beautiful the coast was; tall and steep cliffs, green. The current has taken us a bit too close, we change course and keep the distance.

I have the watch until 4 o’clock. We rise to periscope depth; several steamers, two approaching from astern. We dive to 27 metres. Lunch is cancelled. We don’t want to prepare anything. Tinned food supply is already running low. Surface at 5:30, it is already getting dark. Utmost speed ahead with both oil engines! Very dark, hazy night and one of the most beautiful I have experienced in this war. Lights all around, sometimes a searchlight flares up, several darkened vessels sail closely past us. We wriggle our way through this witch's cauldron, turn around and sail away on opposite course, turn and try again, slipping through a gap between brightly illuminated steamers and the static, darkened sentry vessels - I will never forget this night, well guided by the English beacons on the right and the Irish beacons on the left! At 5 am it is getting more foggy, and the wind is freshening up. At 6 am it is so bad that we can’t see anything anymore. We are only 15-20 nautical miles from the Isle of Man and have to dive! The L.I. takes the depth control and the commander, helmsman, pilot and I go to sleep - so well and deep as I have never slept before. Woken up for lunch.

27. October 1916: At 12:30 we rise to periscope depth to pinpoint our position. But it is too foggy, nothing can be seen. We don’t know where we are. Lunch is cancelled for now. Yesterday I only got some food at 9 pm, a ladle of cabbage, up on deck!

Surface at 4 pm! Lousy weather! Sailing on above water and at 5:22...Isle of Man in sight! Hurrah! Order: ‘Prepare the mines!”. At 7pm, having just reached the starting point for our mine run, we have to dive to evade a large steamer and its escort.

Due to the state of the sea we have to lay the mines at 20 metres distance while on the move; not very nice, if there is only the smallest of leaks the enormous water pressure will push too much water into the boat. But it all goes well! The first mine falls at 7:45 and the last one, the 34th, at 10:28. Change the trim, flood, all done by the books! I am delighted by the praise of the commander! It is a nice feeling to have achieved something proper in the furthermost trench during this war. And now a lot of them will hopefully run into our good mines!

10:30: We surface! Quite a storm! No visibility. We switch on both oil engines and do our best to get away from the scene of our disgraceful deeds! Again we wriggle our way past the individual lights, but there is not as much traffic as last night.

28. October 1916: At 7:45 we dive to evade an escort and an approaching sailing ship coming up from astern. With the sea being in this state that was a good decision anyway. 2:30 we surface again, sailing ship in the far distance. Both oil engines on, course to the south. At 6pm we were still standing 30 nautical miles off the line Smalls Rock and Tuskar Rock. On the portside a large English three-master. We raise the English war ensign. I think tomorrow we’ll have bad weather again.

29. October 1916: From 9 pm to 4 am we are in the sentry line. Hail, rain and heavy seas. Both engines emergency speed ahead we break through it. I have the watch from 11:30 at night to 5 in the morning. Lights all around! At times 18 lights at starboard, and 5 on port! Slowly the Smalls and Tuskar rocks are disappearing from sight, Coningbeg comes into view. We sail up to the height of Queenstown (I have been there as a cadet in 1910). Another 60 to 70 nautical miles and we again become Lords of the Sea! Now, when the first of their ships have run on our mines, let the Beefs block the Irish Sea and search for our U-Boats! Since June 1915 ours is the first boat to sail that far into the wasp’s nest.

Heavy western storm at dawn. Too dangerous for the watch personnel, so the commander wants to dive in the afternoon. We give it one more try however. I have the watch from 12 pm to 4 pm, double straps - but still a horrible feeling of helplessness. On the same watch last Sunday Schliemann was ripped overboard. I am not a superstitious person, but I didn’t dare to ask for the time during this endless watch, I didn’t want to know when it was 2:07! Yet the autumn weather is really beautiful, sunshine … but one would need to be on land, walk through the autumnal forest, or ride across the stubble fields on a Pommeranian estate...in peacetime and victorious!

At 5:30 we dive. Waves too tall, the boat is being lifted up 15 to 20 metres before falling back into the dark, blue valley below. Because of that, several rivets have become leaky, and the boat is taking on a lot of water!

30 October 1916: Weather unchanged. A few hours we stay above water, then we dive again. Nothing in sight up there, we are still near the south-coast of Ireland. Running out of bread. Hard bread issued. I have the middle watch above. St.Elmo’s fire on the mine deflector and the top of the periscope! Huge lightning bolts in the clear sky on the portside. Boat dives at 2:30 pm.

31 October 1916: Boat surfaces at 7 am. Three hours later the commander takes the boat down again as a large amount of water came in through the ajar conning tower hatch. Hard bread is supposed to be issued: the first three boxes have become mouldy, faulty soldered joints. Now the food supplies are very low, particularly as we are not making any progress in this weather! Surfacing at 3pm to continue to march above water. Enormous swell. An escort ship is sighted, but in this weather it can’t do us any harm. We sail on. I have the middle watch. Incredible squalls, pitch black walls of cloud, dark black water, glowing seas around the boat. In front of us and off starboard thunderstorms with hail. St.Elmo’s fire on the mine deflector.

01 November 1916: Have been sailing on the surface for 24 hours already - we can hardly believe it. Beautiful weather. Wind 5-6. Both engines are running to make up for lost time. Course 25 degrees following the magnetic compass! Hurrah! At night hailstorm, sheet lightning and St.Elmo’s fire.

02 November 1916: I am relieved at midnight. It’s mothers birthday so I drink some wine on her health, all the glasses are broken - I drink out of the bottle. A light wind from the west, minimal swell, good weather. The commander takes my watch from 8 to 10:30 to allow me a bit of a lie-in. As head of the mess I donate a tin of cherries to mark the occasion.

3:30 in the evening a steamer comes into sight and we open the hunt on it. It spots us too early and gets away. Has probably reported us via the radio. We turn away to mislead him about our course. Steamer not in sight anymore, returns to the old course, 10 degrees.

To celebrate the birthday, we are having rice soup for dinner and some tins of mackerel in tomato sauce have been donated. The Kommandant raises a toast in honour of my mother’s birthday.

8:07 pm: ‘Alarm!’ Large, darkened steamer about 3000 metres away and running parallel to our course. Auxiliary cruiser! Seems we have been reported! Sadly we lose sight of it, we haven’t been spotted. I have the watch at 2:00 am and want to catch some sleep before I do - but at 11:15: ‘Alarm!’. Auxiliary cruiser, probably the same one, in the moonlight behind us. We turn around to get him and dive to periscope depth when we are about 4000 metres away. But damn, the sea is glowing so bright that the shape of our boat will be fully visible at 13 metres depth while at the same time the glow makes it nearly impossible for us to see anything through the periscope. With heavy hearts we dive to 30 metres.

03 November 1916: During the night the weather has changed: during my middle watch the wind turns from west to south-east and freshens up. The heaviest of storms at midday, wind force 12, enormous waves and terrible swell. On watch from 12:30 to 4 in the evening. Strapped into place on deck, but I will tell them to dive. I only want to get this terrible time behind myself. Boat keels over up to 40 degrees, visibility 500 metres, hailstorm - 4 hours long. I can’t see anything and it is hard to breathe. But I have something to keep me up there, again and again, maybe 1000 times I say to myself: ‘Kawel, stay strong!’. That works and I think about how nice and wonderful the coming period of leave will be - betrothal and Christmas! That gives me the confidence and courage to stay on deck, if only we get back home as soon as possible. Relieved by the helmsman at 4am. At 5:30 he orders the boat to dive.

04 November 1916: Surfacing at 7am: Weather a bit better. Wind turns to north-west over north and then calms down - very odd!

05 November 1916: Barometer 724. Heavy breakers, but we are staying surfaced to make some progress. Middle watch is terrible! Three hours of hailstorm, enormous waves. It just grabs you and throws you into the security belts. Water is freezing cold. My hands are so stiff I can hardly write.

06 November 1916: Wind just changed to south-southeast, still very strong. Clearing up in the direction of the wind, hopefully the weather will improve now! Mood of the crew is not the best - due to the weather. In addition nothing but hard bread and bean soup for the last 8 days. How I look forward to potatoes, bread or eggs, fresh meat! I can hardly imagine such culinary delights anymore.

07 November 1916: Bad weather as usual! Hours of hailstorm, enormous waves, freezing water and ice cold air. At 10 am we change course to starboard. We are on the level of Muckle Flugga. In the evening another change of course to starboard, metre by metre we fight against the heavy sea. The infamous line of sentry vessels is not visible due to the weather. Late evening the storm gets worse and I somehow manage to stay on my watch until 8pm - the worst one yet. My successor reports to the commander at 8:20 that the boat needs to dive. About time, he has been nearly swiped off deck twice.

08 November 1916: Surfacing at 4am. Weather improving steadily. 3:30 in the evening I spot a large fully-rigged three-master on the starboard side. We turn towards it and catch it at 4:20!

Signal: ‘Stop immediately and send a boat over with your papers!’ - Lots of running around on the ship and eventually a reply signal goes up. A boat lowered into the water and slowly rows towards us in the heavy swell. The ship’s name is ‘Solvig of Norge’, a Norwegian from Christiansand, en route from Savannah USA to Copenhagen. Cargo: cotton. We release it at 4:45. Both engines switched on!! Course 155 degrees! On Sunday we can be in Heligoland...if wind and weather allow it. During the evening watch the sea is smooth as glass. For the first time since we embarked the weather is nice with no swell! No moonshine, but night so bright that one could read. Two steamers on portside, pulling out of view.

09 November 1916: Still wonderful weather! Smooth sea, sunshine. On the starboard side a huge steamer with a bad conscience: he spots us too late, but then turns away hard. Enormous clouds of smoke from the funnels, it pulls away in terror making at least 17 knots. We weren’t even interested in him and keep our course. We are installing a new antenna, front half attached to the mine deflector cables and support braces to the mouth of the bun barrel. Looking nice! An extension antenna runs from the deflector braces via the gun towards the stern. The big ships will be marvelling when we come sailing into the Jade!

Since 11am both engines are running at 400 rpm - full speed ahead! Friday evening we can be in Heligoland. And hopefully only good news is waiting for us there! How will it look at the front? In the evening it is getting hazy. We can’t see Horns Reef! As there is no precise dead reckoning, our location is unclear. Still no radio contact. We install another antenna from the periscope towards the stern.

10 November 1916: Finally, in the morning we establish contact with SMS ‘Arkona’. We receive the report that the way to Heligoland is clear of mines. We sound our way towards Chorus Reef and have to halt every two hours to do so. Lots of time lost.

10 am and still no lightship in sight. We try to have our bearing taken with the radiotelegraph - it works! According to this we are 12 nautical miles north of Chorus Reef. Hazy weather, nothing to be seen. After two hours we have our bearing taken again. Now 6 nm south-west of Chorus-Reef! My auxiliary antenna is working exceptionally well!

In the evening, continuous radio contact with Half-Flotilla, ‘Arkona’, ‘Hamburg’, ‘Helgoland-Insel’ and ‘List-Vorpostengruppe’. We order us the beacons and patrol steamers, report locations, suspicious steamer we spotted yesterday night and so on.

At 6 o'clock in the evening, Graadiep and Vyl lightships are in sight. 9 o’clock, Red Cliff lightship - the first German one! 9:10 in the evening we are welcomed by two German patrol boats! Hurrah!

11 November 1916: 4 am, high seas, strong winds! But we are not bothered anymore! 6:30: Trial dive. Foggy, we sound our way towards Heligoland. In the fog we meet a patrol boat which has a precise bearing. We calculate a new course.

Shortly after 10a m: Heligoland dunes in sight! Only visible due to the surge of waves. Then the island of Heligoland becomes visible! Hurra! A few minutes later the order we have been waiting for desperately: ‘All hands ready!’ - we are in the outermost mole, three hoorays from the flotilla boat, from U-55 and the other boats. The band of the Naval artillery is playing on the shore. Then we are welcomed by the Flotilla commander who tells us how proud everyone is of us and U-80 and so on. But most important of all, lots of mail and good news! Everything is well in the theatres of war. Poland has become a kingdom and 1000 other bits of news. Someone has already run into our mine barrier - Hurrah!

END

Cruiser rules is a colloquial phrase referring to the conventions regarding the attacking of a merchant ship by an armed vessel. Here cruiser is meant in its original meaning of a ship sent on an independent mission such as commerce raiding

During the Second World War, Dr. Hans Kawelmacher - then a Fregattenkapitän in the Kriegsmarine - became instigator/assistant in a number of war crimes, including the murder of over 5000 Jewish people in Latvia on 20 September 1941. An article outlining this dark side of the Kawelmacher story and the myth of the ‘clean Kriegsmarine’ is planned for June this year.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nail_Men

Fascinating to read this article Rob.

I recall you researching this a year or two ago and was looking forward to reading the article.

I have huge admiration for the men of the Ubootwaffe in both of the World Wars - indeed all submariners experienced appalling conditions.

The captain of SM U80 during these patrols was a hugely successful commander - surprising he wasn’t awarded the PLM.

great story but I cannot imagine being on such a submarine in such weather! It's a wonder they made it back.