WATERLOO 208: TWO NEW PRUSSIAN ACCOUNTS

PART 1 : 'Now in God's name, strike your blows!', Oberst Freiherr Hiller von Gaertringen, the 'Lion of Plancenoit'

"Ah ! Wellington ought to light a fine candle to old Blucher. Without him, I don't know where His Grace, as they call him, would be; but as for me, I certainly wouldn't be here." - Napoleon on St. Helena

For the 208th anniversary of the Battle of Belle-Alliance I have dug-out two obscure, little known Prussian accounts of the battle which have (to my knowledge) never been translated into English. Mostly ignored in Britain in favour of the mythology created by Lord Wellington, spread by a wealth of Anglo-phonic histories of the Waterloo Campaign, is the fact that in the 1815 campaign Prussian soldiers did most of the marching, fighting and dying. After a brutal defeat at the hands of the French, with some units having suffered up to 40% casualties, Prussian commanders rallied their bloodied troops, conducted a brilliantly executed overnight march through torrential rain and across abysmal roads, before launching themselves into the most decisive attack of the Battle of Waterloo, snatching a certain victory from the hands of Napoleon. On 18 June, Blücher’s starving, dehydrated and bone-tired men threw themselves on the fortified village of Plancenoit and there took on the well-rested and supplied French Imperial Guard in savage close-quarter street and house-to-house fighting. From quite early in the battle, the herculean Prussian effort forced Napoleon to preserve and commit his reserves to stem the Prussian advance; reserves which - had they been available - would have given victory to the French. Prussian troops led the pursuit of the French Army and the race into Paris, which it entered first on 29 June 1815.

Of course, Waterloo was a joint victory of a multi-national force of British, German and Dutch soldiers, yet - not only in popular history - the actual role of the Prussian Army (and that of the Dutch) in the defeat and fall of Napoleon is still often downplayed and ignored. As such, it is no wonder that even after the wonderful efforts of some historians1 to make a German or Prussian perspective accessible to a wider British audience, there are still a wealth of accounts which have not yet been translated2

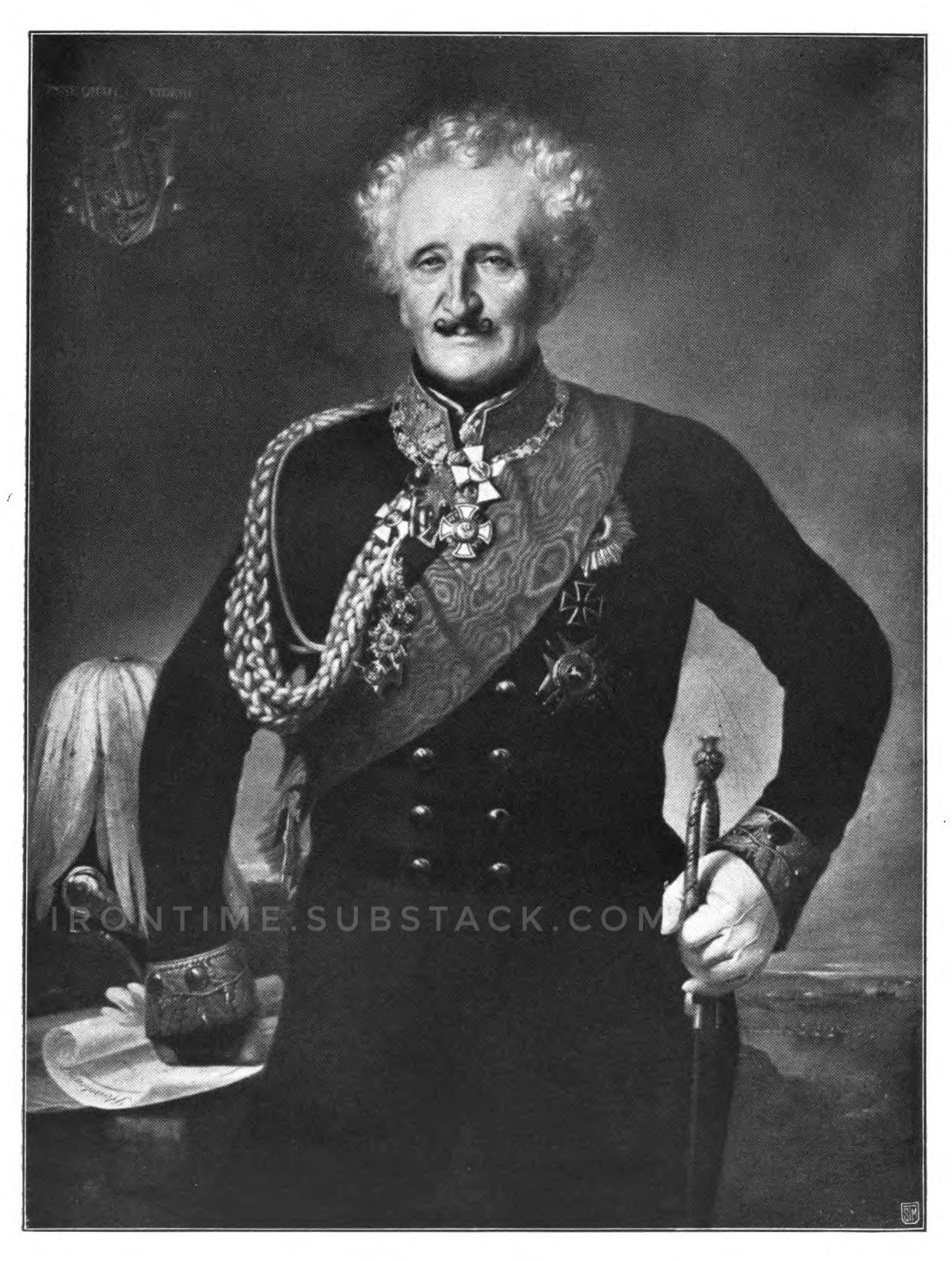

The first account I decided to share with you is taken from the memoirs of General August Freiherr Hiller von Gärtringen, known later as the ‘Hero of Plancenoit’ or the ‘Lion of Plancenoit’, who during the battle led the decisive attack on the village in command of the Prussian 16th Brigade.

His memoirs were published by his granddaughter in 1912. - A full translation of Hiller’s memoirs (by me, or is that ‘bei mich’?) will be available soon (keep an eye on this page). A second account, one by a more junior officer, will be published here later tonight. Both accounts offer a fascinating insight into the ferocity of the fighting in Plancenoit and the chaos of the following pursuit.

Hiller had joined the army on 30 May 1784, when he enlisted in the Prussian von Woldeck infantry regiment on 30 May 1784 as a Corporal. He became an Ensign in 1787 and took part in the fighting in Holland and on the Rhine during the French Revolutionary Wars. As a Second Lieutenant (since 1789) he fought in the campaign against France in 1792/95 at Valmy, Kaiserslautern, Herzogshand, Bubenhausen, Weißenburg, Burrweiler (wounded), Ruppertsberg and at the Schänzel. On 2 March 1802 he was promoted to Staff Captain in his regiment. During the campaign of 1806, Hiller was briefly taken prisoner of war after the surrender of Hameln. After the Peace of Tilsit he was put on half pay. In 1809, as a Captain, he was temporarily district commander in Pasewalk. In 1812 Hiller took part in the campaign in Courland as Adjutant General and Major in Julius von Grawert's staff and later in Yorck's staff. Napoleon Bonaparte honoured him with the Cross of the Legion of Honour, the Prussian King Frederick William III with the Order Pour le Mérite on 18 October 1812. On 28 November 1812, Hiller then became commander of the Spandau garrison. Afterwards, at the beginning of the 1813 campaign, he was initially Adjutant to Yorck and distinguished himself at Großgörschen, Bautzen Katzbach and Möckern. On 31 May 1814, he was awarded the Oak Leaves of the Pour le Mérite for a serious wound he had suffered there and in recognition of his command performance. After a stay in Dessau to recover, he was already back with the forces at the end of December, crossed the Rhine under Blücher and led the Prussian 1st Infantry Brigade to Paris. Before the end of the campaign, he was appointed commander of Minden on 17 March 1815.

In 1815 the Battle of Waterloo, Oberst (Colonel) Hiller led the decisive advance on Plancenois in command of 16th Brigade. Thereupon promoted to Major-General, he came to Stettin in 1816 as commander and at the same time acted there as inspector of the Landwehr in the government department. He was then transferred to Posen in 1817 as brigade commander of the troops brigade. In 1827 Hiller took over the 11th Division in Breslau and was promoted to lieutenant general shortly afterwards. On 23 June 1830 Hiller took his leave, which was granted with an annual pension of 3430 Taler. In the following years, he received several more awards for his services. On 3 September 1840 he was awarded the Red Eagle Order I. Class with Oak Leaves, on 23 August 1852 the Grand Commander’s Cross of the Royal House Order of Hohenzollern and on 18 January 1853 the Black Eagle Order.

'Had it not been my dear comrade's brigade, I would envy him to have decided the Battle of la Belle-Alliance'. - Prince Wilhelm of Prussia

1815: Reminisces of Freiherr Hiller von Gaertingen

(...) ‘On the 18th before daybreak I received orders to withdraw the pickets, to march from the bivouac on the right to Wavre, to cross the Dyle there, and then to direct the march towards St. Lambert and await further orders in front of the section there. The bad roads caused so many stops that I didn't get moving until 6 am. Although during the passage of the 16th Brigade through Wavre, where Field Marshal Blücher's headquarters was located, there was a fire there, it did not particularly stop my march, as my artillery and cavalry had already passed through and the infantry remained in good order. I was fortunate enough to receive a wagon with food, some flour, bread, bacon and brandy for my troops from the Royal Intendant in Wavre and used the time to distribute it quickly wherever I was allowed to stop. Arriving at 2 o'clock in the afternoon at the assembly point of the 4th Army Corps on this side of the village of Chapelle St. Lambert, I saw Zieten's Army Corps turning to the right towards Ohain, and soon afterwards I received orders to pass through the section of Lasne and to continue advancing in the direction of Frichermont. In front of the 16th Brigade, the 15th marched, the reserve cavalry followed me. The vanguard was already ahead without much difficulty, notwithstanding the soggy ground. Our artillery, however, had to be partly helped along by the infantry on the worn-out and bad roads. Thus, while the cannon fire from Waterloo could be heard more and more clearly, without having discovered anything of the enemy, the brigade reached the forest called Bois de Paris. Here I was ordered to halt at about 3 o'clock in the afternoon to await the reserve artillery and the 13th and 14th Brigade, which were still in the narrows of St. Lambert, while we drew up the infantry in columns close together on both sides of the road from Lasne to Plancenoit. The artillery remained on the road itself, the cavalry then marched up behind the forest, ready to follow the infantry. General von Bülow went to a height towards Frichermont, outside the forest, to reconnoitre the enemy. A detachment of the 2nd Silesian Hussar Regiment, which formed the head of our advance guard, had already searched the Paris forest earlier and found it completely unoccupied, nor had it noticed any signs that the enemy had undertaken any effort to secure his right flank. On a hill more to the front, outside the forest, one could overlook the movements of the French and English, and Field Marshal Blücher arrived there too and then rode alongside the troops. When the men wanted to express their joy at seeing their beloved leader in the lead again, Count Gneisenau beckoned them to keep quiet. Father Blücher greeted the troops and then went to Count Bülow.

The thunder of the guns and the sound of musketry, the music of heroes, grew stronger and stronger. At about 4 o'clock, the approach of enemy cavalry against us was noticed, at least by the cavalry of the French General Domon, whom Napoleon had already sent to the right wing at about 1 o'clock in the afternoon, in order to monitor the possible advance of troops over St. Lambert, to get in touch with them in case it was Grouchy, as the French suspected, or to prevent them from advancing if they were enemies. For this purpose the brigade Domon had advanced a distance in the direction of the forest of Paris and then marched up in a hook behind the right wing of the French army; so far, however, it had contented itself only with sending out patrols, from which, as the French reports assert, a hussar of the previously mentioned detachment of the 2nd Silesian Hussar Regiment was captured, through whose testimony Napoleon claims to have first learned of the approach of Bülow's corps. According to the observations made by our advance troops from the heights in front of the forest, however, it is asserted that the French cavalry under Domon did not take up the position against the Bois de Paris until much later, and the assertion that a Prussian hussar of the advanced detachment was captured is also denied by the regiment in question. In any case, I can confirm that the part of the enemy cavalry which was now (4 o'clock in the afternoon) approaching the woods which my skirmishers had occupied, did not seem to be very well informed about what was waiting in the woods, nor did they show any desire to find out exactly what was going on.

'Today we must take revenge for Ligny'

After having received orders to try and catch the enemy cavalry approaching the forest from Plancenoit, and after having withdrawn the fusiliers of the advance guard from the edge of the forest in order to draw the enemy closer, I noticed that the enemy, still more than 100 paces from the edge of the forest, turned back after some reflection without sending a patrol into the forest or leaving a troop behind. Soon after, His Royal Highness the Prince Wilhelm came trotting forward at the head of some of the reserve cavalry on their way to Plancenoit. The hero who I knew well from the campaigns of 1813 and 1814, as handsome as a young Mars, at the head of part of his troops with drawn sword, greeted me as I rode by, and no sooner had he left the woods than he marched up and charged the retreating enemy cavalry, which was thrown back to the cover of the guns of the batteries deployed beyond the village of Plancenoit - a triumph for all who could see this charge. This cavalry advance also covered the development of our infantry after stepping out of the woods, which, although the two rear brigades had not yet approached, began about half-past four o'clock, in such a manner that I advanced with the 16th Brigade on the left of the road to Plancenoit, while General von Losthin with the 15th Brigade moved out on the right of this road. I advanced in columns towards the centre, developed as soon as I had space in the brigade formation and marched rapidly further forward, at the same time pushing forward skirmishers with their supports. In the meantime I received fire with roundshot from the batteries on the other side, some of which hit the columns and tore down several pairs of men; among those hit by one of those iron balls was the brave Hauptmann Zimmermann of the 2nd Silesian Landwehr Regiment who was mortally wounded while his son, a youth who was carrying the flag and who, as far as I know still serves in the army as a Major, was wounded. In order to draw the troops as far as possible out of the enemy's line of fire, I sought to gain a high ground in front of me, which was hereafter occupied by the brigade's artillery, and from where I could see the village of Plancenoit in front of me and judge that we were standing quite perpendicularly on the right flank of the French main position. Having the village in front of me immediately in view, I then advanced the left wing of my riflemen in the bushy and hilly section of ground which forms the edge of the valley of the Lasne stream, little by little up to the first houses of Plancenoit, where they then entrenched themselves and held on during the fight for this village until its final capture. In the meantime, General Count Gneisenau came to my front and called out to me from afar: 'Today we must take revenge for Ligny'. Shortly after these words, an enemy cannonball shattered the right leg of his horse, so that it collapsed and the General came to rest under it. I rushed to help. In the meantime, the horse got up again without injuring him, so that I exclaimed delightedly: 'Thank God that they are alive, now we will also be victorious today!’ Gneisenau smiled, had another horse brought to him and asked me to have the poor animal, wounded under him, shot to death. He then told me the general disposition, according to which the goal of our advance should be the outpost of Belle-Alliance, lying on a hill and visible everywhere, whereby I should generally follow the movements of the right wing and not proceed hastily at all, but prepare the assault by advancing gradually with artillery support. The Lasne stream was designated as the leaning axis of my left wing; to cover it, the general instructed me to send two battalions from my brigade to the left of the stream into the hilly and overgrown terrain mentioned above; They were to keep an eye on the area beyond, report any enemy troops approaching from the Dyle or the Lasne stream as quickly as possible, liaise as far as possible with Major von Falkenhausen, who was on the other side of the Lasne stream with a Silesian Landwehr cavalry regiment, and cover the left flank of Bulow's corps as far as possible. I entrusted Major von Keller with this detachment, consisting of his fusilier battalion of the 15th Regiment and the 3rd Battalion of the First Silesian Landwehr Regiment under Major von Seydlitz, namely the left wing battalions of my brigade formation, which until then had served as advance guard; I also added a troop of Landwehr cavalry to report any incidents as quickly as possible.

Oberst von Valentini, Chief of the General Staff of the 4th Army Corps, now also brought me the instruction that in the general attack of the corps was to be directed at heights of Belle-Alliance, where some houses were clearly visible and where one could notice some kind of scaffolding, also many troops. This was the only disposition I received during the battle. I then hurried to instruct Major von Keller on his position and trotted forward with him and the cavalry troop, the battalions following as concealed as possible. These two battalions did not come into action at all during the battle, and only advanced in the direction of la Maison du Roi during the final assault on Plancenoit, from where I also received the first report from Major von Keller. For my part, after I had positioned my remaining troops in such a way that they were fairly covered against the solid shot and the enemy shells mostly flew over them, I rode on to a height where I noticed Field Marshal Blücher with his suite, in order to inform him of my position. Meanwhile, the reserve artillery gradually approached and chose their positions. Here an increasingly fierce artillery battle immediately ensued, whereby, although my battalions often found a little protection against the enemy's cannon fire through small footholds of the undulating terrain, which was carefully used, they nevertheless suffered not insignificant losses, without, however, showing the slightest disorder. A battalion of fusiliers of the 15th Brigade, which was in front of the 16th Brigade and cavalry to cover our batteries, had expended its ammunition during the general advance of the artillery; I was ordered to replace it with the 3rd Battalion of the 2nd Silesian Landwehr Regiment under the direction of Captain von Dobschütz of the 15th Infantry Regiment, who distinguished himself on this occasion.

'Now in God's name, strike your blows!'

Our artillery fire was directed especially against the enemy columns moving from Belle-Alliance towards Plancenoit, and among which one thought to discern Imperial Guards through the telescopes. Opposite us, the VI French Corps (Lobau) and the Young Guard, which had hitherto formed part of Napoleon's reserve on the heights back of Plancenoit, were forming up. The French fire against the English army was increasing. Field Marshal Blücher, watching Plancenoit ahead of us, said, so that I could hear, 'If only we had that cursed village!’ I moved a little closer and said: 'If you order me, I will take it, the houses on the left are already occupied by my tirailleurs'. The Feldmarschall said to Count Gneisenau: 'Shall we let him loose?' To which the latter replied: 'I think the moment is right!’ Whereupon Blücher, pointing to the approaching enemy columns, exclaimed: 'Don't you see what that fellow is pushing in there?' To which I dared to reply: 'I'll be in there sooner than they are, if only you'll let me have the best support'. 'Now in God's name, strike your blows!' remarked Blücher.

I immediately dashed to my troops, ordered the first echelon, namely the two battalions of the 15th Infantry Regiment under Major von Wittich, to seize Plancenoit on the right side (from the north), as well as the two battalions of the 1st Silesian Landwehr Regiment under Major von Fischer on the left to go straight at the village, while the 2nd echelon, consisting of the remaining two battalions of the 2nd Silesian Landwehr Regiment, under Major von Blandowsky, to go straight at the village as well. At the same time I gave urgent orders to overthrow everything in front of us with the bayonet, no matter at what cost; apart from the riflemen and the artillery, no one was to fire until we were beyond the village.

Two battalions from the 14th Brigade (Ryssel), which had arrived in the meantime at about 6 o'clock, and the first battalions of the 11th Line and 1st Pomeranian Landwehr Regiments were sent after me as reserves, in response to my notion that, since the 15th Brigade had moved away from me on the far right, I would be too weak to carry out the attack alone. They, however, followed my attack at a great distance. The artillery remained in position. I ordered the good Rittmeister von Osten, who was in command of my brigade cavalry, to position himself in the Plancenoit depression in order to collect everything that might retreat from the attacking force. I also briefly reminded them that if one of the leaders fell, the second, and so on, the younger one, responsible for honour and duty, would have to take command. I vigorously encouraged the troops of all three columns as I rode past, and so, in the face of the commanding General, the attack proceeded in the most perfect calm, but at a trotting run, from solid shot and shell fire into canister and finally musket fire, but with comparatively little loss of men. On the right, Major von Wittich reached the hollow way which abuts the middle of the northern edge of the village; the two columns advancing more to the left of him also threw back the enemy and surprised a howitzer, two cannons and several ammunition wagons in the front of the village, which were in the process of retreat, and took them without great loss. I entered in the middle and, seeing the walled churchyard dominating the area, I kept a battalion there in order to garrison it, while I tried to take the rest of the village with the remaining troops. I immediately reported the success of the first attempt and asked for support, but repeatedly in vain. In the meantime, I tried to consolidate my gains as much as possible; I found the churchyard surrounded by a poor wall, which was too high to shoot over and too thick to hew holes in. I had the church opened at once, in order to take out the benches and make a kind of firing step, and to barricade the entrances; an attempt was also made to throw down the upper part of the wall. But all this had to be done under the heavy fire from the houses surrounding the churchyard, which were still held by the enemy and were some 30 paces away. While I was busily engaged in these arrangements, relying on my advanced, brave troops, who were all fighting, and certainly hoping for a fairly vigorous push from the army, Major von Fischer reported to me: ‘We can no longer hold, the Landwehr troops are retreating one by one. The enemy columns, consisting of troops of the Young Guard, are advancing just as heartily as we are.’

I threw myself on my horse, gave the battalion standing with me the order to hold the churchyard until I gave the signal to retreat, and charged forward with Major von Fischer. At that moment my horse was shot; before I could get another, my left wing in particular turned more and more to retreat. An enemy column came storming tambour battant towards the still large opening in the churchyard wall. In front of it I later found the enemy Tamburmajor, a handsome man, lying shot down in front of the opening. The battalion defended itself vigorously; but at the same time it widened an opening in the wall in its rear and soon, after having lost many men, was driven through it from the churchyard, where the enemy then very soon consolidated the more favourable position of the same for his defence. As I did not see any support approaching, I ordered the signal to slowly fall back to be sounded which, although in a rather disorderly manner, was carried out well enough without discouraging the troops. If I then had had only two battalions in the village to support me, I believe I would have succeeded in becoming master of the place then, and the results of the battle would then have been even more significant, but the loss on our side much less. Due to a lack of horses, we had to leave the captured guns, partly overturned, behind, without being able to spike them, as we did not have the necessary material. Only in the very dark of night did we regain possession of them. During the first attack, I had chosen a convenient approach almost in the middle of the village, which I wanted to use immediately for a second attack, after having had an obstructing wall thrown down on this spot during my retreat. I watched the enemy, drunk with victory, who followed my riflemen fiercely along the paths to the right and left of the village, especially those of the 15th Regiment to the right, and seemed to have no regard at all for a way out in the middle across a courtyard which, as I have already mentioned, I had chosen for a second attack and which, moreover, could be fired into by my artillery. On returning to the cavalry I had left behind, I found the greater part of my infantry in a process of forming up. Major von Wittich had retreated more to the right; the French cavalry, which had pursued him there, had been forced to turn back by the fire of our artillery.

I now gathered and formed my troops again as quickly as possible for a second attack, which was launched similarly to the first, only with reinforced troops. The first battalions of the 11th Line and 1st Pomeranian Landwehr Regiments, which had followed in support, were joined by the two second battalions of these regiments; Major von Wittich led these troops, united with the two reorganised battalions of the 15th Infantry Regiment, once again as a right attack column against Plancenoit. I led all the remaining infantry in a column attack against the middle part of the village, which I mentioned earlier, and where Major von Fischer's riflemen were still holding the last houses of the village.

Whereas before we had had to deal with Napoleon's Young Guard, we were now to find the troops of the Old Guard facing us, a sign that the enemy had been forced to use his last reserves. I first entered the village again by the designated route, as far as the centre, in the hope of capturing the churchyard, and in the certain conviction that the enemy on our right flank would already be considerably harassed by Major von Wittich's attack. We advanced over corpses with the bayonet, but suddenly came upon the battalions of the Old Guard, which Napoleon had sent under General Morand for reinforcement; we immediately got into a murderous melee with them. At first we pushed them back, taking them by surprise, but I ordered them to withdraw for the second time, and we were fired on from all sides at the same time, especially from the churchyard. I moved everything towards my left wing, where Major von Fischer, with the first Silesian Landwehr regiment, formed my reserve.

The enemy fiercely pursued both my troops and Major Wittich's column, which was also retreating. On this occasion, Major Wittich once again showed remarkable activity and bravura. He rallied and reorganised his men as quickly as possible, sought support where he could find it and, in order to gain time for reorganising, himself cut into the pursuing French troops with Wolff's squadron of the 2nd Silesian Hussar Regiment, so that they fled back to the village, many throwing away their muskets.

I and my column, after a considerable loss and almost completely exhausted, arrived on my extreme left wing behind the last houses, still heavily shelled by the artillery; where, unfortunately, I lost a second beautiful horse. The gap between my brigade and the 15th, which had formed in the advance towards Frichermont and Plancenoit, had at first been filled by the 14th and 13th brigades, the former following me straight on, the latter drawing more to the right towards the 15th brigade; but this had now again created a gap between the 14th and 15th brigades, and this was now filled by the main body of reserve cavalry under Prince Wilhelm. It was this cavalry which, by its good bearing and firmness, forced the enemy to remain on the defensive by repeatedly advancing into musketry fire in support of the infantry returning from the village attacks. Thus I succeeded quite unperturbed in reorganising my infantry, which was naturally in a state of disorder, and in encouraging it to launch a new attack.

It was at this time that Napoleon, having become reinforcements to Plancenoit, ordered the last great attack on Wellington's main position. Around this time, Field Marshal Blücher sent Oberstleutnant von Thile of the General Staff to me to inform himself of my situation and me of the decided general attack on our part, with the participation of our last reserves of the 2nd Army Corps. While we were talking to each other, a cannonball flew so close between our heads that we both congratulated ourselves on having escaped unscathed. I now prepared for a third attack, for which I received fresh ammunition. At some distance, General von Tippelskirch rode over and called out: 'Good day, Hiller! How are you?' I replied: 'A bit hot!’ However, I saw nothing of his brigade, the 5th in the 2nd Army Corps, which is marked in Siborn's map in front of me during the last and third attack on Plancenoit, just as I saw nothing of General Graf Bülow von Dennewitz, from whom I was later questioned about this circumstance and about the presence of General von Tippelskirch. The battle was in its hottest period on all sides; the day was beginning to draw in. Several troops of the enemy were seen advancing on the road from Genappe to Brussels, but returning in disorder to Genappe. The field tracks, especially where the ground sloped, were almost unusable, which is why, soon after the enemy had been driven off the road, almost all his guns got stuck in them. The enemy set fire to several houses in Plancenoit and repulsed all attempts made from various sides against this village by the freshly arriving troops, until I finally received orders from Oberst von Valentini to advance once again with all my might. I now again ordered the storming of the ominous churchyard as the target of the attack. It was carried out on the right wing by the 15th Infantry Regiment, which was gradually joined by the entire 14th (Ryssel) and part of the 5th Brigade (Tippelskirch), while a battalion of the 2nd Silesian Landwehr Regiment led the left assault column. This time the attack succeeded completely and with relatively few casualties. The enemy had already been made quite tired and was also burdened by the burning houses, which were, by the way, full of severely wounded and dying men. My brave regimental and battalion leaders von Wittich and von Fischer, von Blandkowsky, von Bock, etc., supported me most vigorously and joined me again on the concentrically attacked point. In the slaughter, mostly with the bayonet, a handsome, tall guard officer rushed towards me, demanding pardon. But before he could reach my horse, he was already pierced by several bayonets. I still have his sabre of honour, engraved with the symbols of the Republic, the Empire and the Restoration. The troops, who had been exhausted, did their utmost to occupy the churchyard, as a soulful courage and the highest bitterness against the enemy could do. Little pardon was given. I left most of my troops in the brightly lit churchyard, with orders to rescue the wounded from the burning houses and to extinguish the fire as far as possible. With about two battalions I moved further beyond Plancenoit towards the Brussels road, but received fire from the direction of the heights of Belle-Alliance, probably from English batteries, who mistook me for the enemy in the dusk, and several more men were killed. I sent my general staff officer, Hauptmann von Reichenbach, to meet the fire, to give information about our situation and to direct the fire, and pushed my battalions back to Plancenoit, as I did not want to sacrifice several more men unnecessarily. Here I received word from Major von Keller that he had bypassed Plancenoit on the left in the bushy heights and had come as far as Vieux Manans in the direction of Maison du Roi, joining the general advance.

‘Whoever still has a breath and a drop of Prussian blood in his veins must now pursue the enemy!’

At 10 o'clock in the evening General Gneisenau appeared with the 2nd Dragoon Regiment with the words: 'Whoever still has a breath and a drop of Prussian blood in his veins must now pursue the enemy! --- My dear Hiller, prepare yourself for this!' I pointed out the impossibility of demanding anything from the exhausted and thinned out battalions at this moment, but suggested that the two battalions under Major von Keller, which had hardly come to fire at all, be used provisionally for further pursuit. General Count Gneisenau was very pleased with my suggestion, gave the necessary orders and shook my hand with the words: 'As soon as you can, follow me to Quatre-Bras'. I got the troops in some order, ordered ammunition to be distributed and three cheers to be given for His Majesty the King. Rifles were stacked, fires extinguished, care was taken of the wounded and food was brought up. More and more scattered men, including some English infantrymen, found their way to me; likewise, several enemy soldiers demanded shelter and protection, which was granted to them. At 6 o'clock in the morning, however, I started the march to Genappe with the weak rest of the brigade on the Brussels chaussee.

Many scattered Frenchmen whom we picked up on the march were sent back without further escort, many unmanned guns and ammunition wagons left unattended; even the two howitzers and guns which the 16th Brigade had captured at the first attempt on Plancenoit were still found in the hollow of the village. Before reaching Genappe, the troops had to march over corpses of crushed men and horses. Immediately at the entrance to Genappe, a filled and opened French ammunition wagon almost completely blocked the way. On the wagon hung a burning fuse and on it sat a grenadier of Napoleon's Old Guard with a shattered leg, a handsome old warrior, calmly awaiting the moment when the fuse would end and destroy him and at the same time a host of his Emperor's enemies. I luckily noticed the burning fuse myself, had it cut off, took the wounded man to a house and and my orderly handed him a bottle with some wine. I will never forget the look with which this decorated dying hero returned the emptied bottle with a 'merci camerade!'

Genappe itself was teeming with troops from the vanguard, fusiliers and Landwehr, cavalry and infantry and other troops, friends and foes, who plundered the Emperor's wagons like busy ants; at times the road was so clogged with cannon and wagons that it took me, along with a few infantry, a long time to meander along it to Quatre-Bras, my infantrymen also dispersing in order to partake of the looting. In order to keep the men together, harsh discipline was no longer applicable. An alleged orderly officer of the emperor joined me ( I have forgotten his name) and asked me for protection. In the tumult I had him put on one of my hand horses, made him notice to keep close to me until I would send him under escort to headquarters. He told me that the whole of Napoleon's equipage had been surprised by our advance party at Genappe on the run to Charleroi, because the chief of the equipage had been waiting for a direct order from the Emperor and had not wanted to believe the fugitives that the battle could be so totally lost, all the more so because on the 16th after the battle of Ligny he had been severely criticised by the Emperor for having returned to Charleroi with the cavalry without the Emperor's order, and not having gone to Fleurus, because he had mistaken the forces of Ney's army under d'Erlon for enemies. I asked what reason the Emperor could have had for carrying so many jewels with him during the war, as were found in the wagons by the fusiliers of the 15 Regiment, and some of which were thrown away - Thus a young fusilier found a whole string of solitaires of certainly very high value, which he put into his haversack. Unfortunately, there was a hole in it and he lost at least a quarter of a million Talers. The whole terrain was later said to have been sifted through by speculators and great profit was made in the process, as the fusiliers threw several boxes of jewels, which they thought were glass, into the dung and looked for money instead. My prisoner replied that the Emperor had taken all the crown jewels from Paris to deposit them in Brussels in exchange for a large sum of money for the use of continuing the war. Incidentally, a large mass of silverware, allegedly 60 bags of plates, spoons, knives, forks, cups and so on, was found, some still marked with the arms of the Bourbons, some with the imperial N and crown, dragged along by the soldiers and, when it became too heavy, partly thrown away again and picked up by others who followed.

An hour behind Genappe, General von Bülow allowed the brigade to rest and cook. here was the first rest since 15 June for my exhausted but overjoyed forces, in which the consequences of the battle only became fully apparent as the day wore on. we found many of the old Guard soldiers in the surrounding villages already dressed in civilian blouses. It was also only now that it was possible to reassemble my forces and put them in complete order, in order to overlook the loss of men. In the bivouac on the 19th in the morning, the officers of the 16th Brigade presented me with a laurel branch on a silver plate, a cup with the Bourbon coat of arms and a pair of Napoleon's silver spurs from the Emperor's carriage as a memento. I still have the plate, with the stipulation that it should remain with my family. The laurel, too, which is to be placed in my grave. In Frankfurt am Main, together with several officers of the brigade, I presented the cup to Minister von Stein, who kept it in honour at his castle in Nassau (...).

I recommend looking at the works of Peter Hofschroer and Paul Dawson, as well as the translations of German source material published by Gareth Glover.

A lot of ‘new’ German accounts from the Napoleonic Wars will be available soon ;) [keep an eye on my substack for news].

Thank you. It’s incredible to read this first hand account of battle.