'WITH THE BEST GREETINGS, THE SLAYER OF FRENCHMEN' (3)

The letters of a 17-year old Berlin war volunteer from Belgium and France, 1914/1915, Part 3

NOTE1

When Regiment 201 moved into the Menin area in the second half of December 1914, no one suspected that they would remain in and around the walls of this town for over 4 months. Never again would the regiment remain so in one place for so long. Menin (Flemish: Mêenn [ˈmeːnən] or Mêende [ˈmeːndə]) lies right on the French border on the Lys River, which separates it from the neighbouring town of Halluin, which is just over half the size. Before the First World War, Menin had a population of about 20,000. For a time, the town had been in Austrian possession and was defended by Austrians and Hanoverians against a French army in 1794. The later General Scharnhorst, at that time still a Hanoverian artillery officer, played his first major role in this conflict.

The long stay in Menin was intended to give the regiment the opportunity and time for further training, and was diligently used for this purpose. Marching exercises, shooting, patrolling, attacking, defending, pursuing, bringing up reserves; a rich programme of training unfolded day after day in Menin's environs. Every day the regiment, by then jokingly known as the '1st Flanders Guards Regiment', returned to its garrison town, dusty and filthy, to the sound of the regimental music. A much-used training ground for the regiment was the 'Van der Mersch' square, which in those days looked very much like a German barrack yard. On 13 February, General von Deimling inspected the regiment. During its long stay in Menin, Regiment 201 was a corps reserve of the XV.A.K. and was temporarily deployed on the Ypres front, e.g. from 14 to 21 January at Zillebeke and from 30 January to 6 February 1915 at Hollebeke.

Menin, 3 January 1915: My dears! Now I am in Belgium again for a change. And dear Adolf, it seems that we are once again wiser than you, Russia is said to be negotiating peace with us from today. I hope you're already that clever. It's supposed to be true. Frau Walter has already written to me to lament her misfortune, and wished that her son-in-law would also be in the field, so that his laziness could be driven out of him. Dear Mother, I am delighted that two large parcels are on their way for me, but don't take it amiss if I have to tell you not to send me any more large parcels. An infantryman cannot afford this luxury. We can't pack anything away and so I always have to distribute everything I receive to my comrades. Especially when two big cakes arrive at once. Send me everything in small parcels. More often for that. The aspic chops were fabulous! But even so, I had to give half away because we had an alarm and we can't go to war with a parcel under our arm. Then, unfortunately, small parcels arrive at the same time and then I'm stuck here or I have an upset stomach. By the way, I would be happy with a rolled ham. A small cheap one. Lard is probably on its way. That's it for now. An alarm is expected. Hearty greetings and kisses from your Alex.

Menin, 4 January 1 915: To all my dear ones! After receiving parcels 32 and 33 yesterday, sister's letter of 24. December reached me today. At first I am disappointed at the number of lace items you have received. I sent one lace blanket and one collar in parcel 17 of 11 December. Then one and two days later, another one, making a total of two collars in letters. As these last two were also the most beautiful and expensive, it is directly annoying that they did not arrive. Stupidly, I wrote 'Christmas letter' on them and I guess the gentlemen at the postal service also wanted to receive a gift. Unfortunately at the expense of those standing out in the fire. It is a shame! I hope I was wrong about that! Dear Adolf, I am infinitely sorry that I have offended you by an ill-considered joke. I am directly saddened by it. I hope we can make up again. But please, believe me, if even the artillerymen pity us, please believe me that we don't have it easy here. You are right to look forward to the draft, but the father is also right not to do so. And dear little Lotti, please don't see me marching into Berlin too soon! I spent a night on watch with a comrade, he told me what he was going to do in Berlin when he returned. The next day he was dead. Yesterday we received a letter from his relatives expressing their Christmas thoughts. 'How did he fall?', 'Where is he buried?', these were the key questions. We received three or four such letters. And it is so difficult for us to answer them. What are the numbers of the letters you received? Three large and seven small parcels are a lot, but for us Prussians, nothing is impossible! Our journey to Ostend does not seem to be coming to anything for the time being, but our next march will be towards Ypres. Hill 60 has been captured again, and maybe we'll go there. We hear a lot of fantastic rumours from there. But they are true, even if they sound like fairy tales. Someone gets out of the trench with cigars in his hand, walks the 20 metres over to the enemy and hands out the cigars to the French, and what do they get in return? A truce! Neither party fires any more. Negotiators also go to the artillery in the rear to silence the guns. Now isn't that droll? Obviously, once we're there, this friendly business won't happen again. We'd rather wage war. Lard is still eagerly awaited. Sausage wanted. Ham tastes good! Don't forget to send Lard! Candles make the room bright! A comb scares away the lice! Peace is the main thing! Until then, endless and dreary times are in sight. Warm greetings and kisses from your son and brother Alex.

Menin, 6 January 1915: Dear parents and brothers and sisters! Unfortunately there are no parcels for a few days. Couldn't have been a worse time for that. Dry' bread is now the main staple food again. Money is also scarce. Dear Adolf! I am really diligent and set you a good example. And let's hope that we can write many a letter in the next six months, which we certainly still have ahead of us. Hopefully I'll be home soon and then I can tell you about 'our' badge of valour, and if you want to see 'our' Iron Cross, go to Sergeant Lieber. He wears it for the old 7th Company. For the days at Merkem across the Yser Canal, where we caught the infernal shellfire. Here on the entire line the positions are not much better, but the enemy fire is not so concentrated on single points. All the regiments are being replenished here, which is something, I think. Maybe we'll be a little wiser in four weeks. There are so many new men coming here that there are only weapons for 75% of them, which of course has a reason. Austria has been given a million and the Turks half a million. Today the order has been issued that all communication with the enemy is forbidden. Our other brigade is at Nieuport and is said to have enormous losses there! The shit, respectfully speaking, must finally come to an end. To have shells whizzing around your ears over and over again in the same place is a disgusting business. And let's hope that one day we'll get back home again. Bormann has written to me. He is very pleased and tells me that the content of my letters is appreciated by everyone. Please be very, very careful, as can get into all kinds of trouble due to my statements! Dear Mother, thank you very much for your kind, handwritten lines of 1 January 1915. I have received the knife and scarf and everything else. Yes, Mother, it is my wish to see you once again, safe and sound, after a victorious peace. Let's hope for the best. Best regards from your son and brother Alex.

Menin, 9 January 1915: All my loved ones! Parcel numbers 34, 35, 36, 38 and 40 arrived. Lots of sweet things that taste delicious. Today my letter will probably not be so long, I don't feel quite well. Tonsillitis and gastro-intestinal problems. I can't seem to tolerate the food any more. Imagine: Just green rice, yellow rice, brown rice and water. A greyish mass floats on top and the hard grains float at the bottom, which you have to chew with all your might. Then everyone gets a quarter of a litre of wine. I threw up like a Kaiser afterwards and my comrades all got pale faces and threw themselves on their straw beds. Since that quarter of a litre of wine, I've had it with Belgian wine. Cheap Moselle wine for 75 Pfennigs a bottle is better and, above all, it doesn't make you vomit. Today I went to the cinema. Directly pompous for a place like Menin. A purpose-built house, a string concert, which I haven't heard since 10 August, by our military musicians and then the usual stuff. I was glad to see nothing of the war for a change. On the 13th we'll probably go forward and I hope I'll come back again. Now, a son and brother sends his best regards.

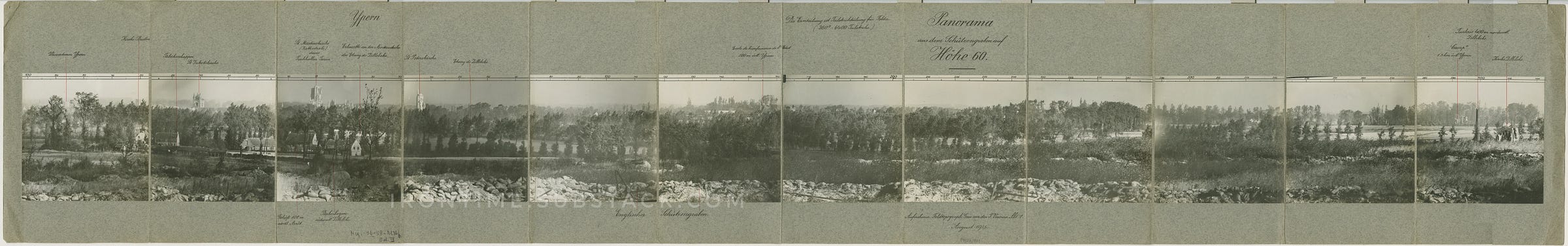

Menin, 13 January 1915: My dear family! Before we get to the trenches, I want to write you a few lines. It is now 6:30 a.m.; at 11:30 a.m. we march off and will have another strenuous three or four hour march until we reach the trenches. There we will be relieved after 48 hours and march back to the alarm quarters, where our coats and uniforms are usually washed. It is only 48 hours, but that is enough to exhaust you completely. We're moving into the positions on the right of the fiercely contested Hill 60. Forward with God! Dear little Lotte, you write with such great confidence about a reunion next year, but please understand that I don't have the same confidence at the moment - there's just no way of knowing. But let's hope for the best. Perhaps you'll hear from me again in three days' time. I want to close now to rest a little more. Farewell! Goodbye! With many warm greetings from your son and brother Alex.

Between 14 and 21 January 1915, the regiment was again deployed south at Zillebeke, where it moved into the trenches vacated by IR 136. In the night from the 16th to the 17th the II Battalion moved as a reserve to the barrack camp Zaandvoorde and on the night of 21 January back to its old quarters in Menin.

Zandvoorde, 17 January 1915: Dear parents and brothers and sisters! At last I can write the lines you have been waiting for so eagerly. As I have already written to you, we were in the lines for three days and three nights on the right of the notorious Hills 58 and 60. As much and as terribly as they fought at Hill 60, it was peaceful for us only 500 metres further away. There we got to know a whole new side of the war. We were situated in a forest, but nothing could be seen of the treetops any more, as they had been shot away, and on our left wing we were facing the enemy at a distance of only eight metres. I kid you not! Our whole position looked like an allotment garden colony; the trench with good dugouts and behind it the reserve trench. And the most beautiful thing was, that both friend and foe climbed over the parapet to chop wood to make coffee. You wouldn't even think of shooting if someone behaved so casually. And the fires burned peacefully in all the places and everyone made their coffee. At the trench opposite us, the Frenchmen and we were peacefully looking across the parapet and the gentlemen over there were waving at us cheerfully. They also tried to make conversation, but we couldn't understand anything because of the stormy weather. They even threw us a few tins of food. Our Rittmeister von Heyden took their photograph and they held still for the camera. Then one of us shot a Frenchman in the foot, whereupon they got angry and let their machine guns play. But it was a waste of ammunition. Well! Can you blame them? While they are chopping wood to make coffee, they are disturbed in such an ill-mannered fashion. While we were enjoying this peaceful Tête-à-Tête, shell after shell whizzed into the trench 500 metres away. Yesterday they also fired at us, but without success, because without howitzers they can't do any damage to our position. However, as good as the position was, the route which let us there and which we used to fetch food was awful. I can tell you, it's certainly a good path for an American Indian to sneak around on, but it's nothing for an educated Central European. When you think: 'Now all is clear', a flare shoots up and you have to stick your nose in the mud to avoid being seen. This manoeuvre repeats itself about 50 times along the way. And you can imagine what that means, when you are not allowed to sleep day and night. The whole ground here is riddled with trenches and the situation is so confusing that many a man has accidentally strayed into the enemy trenches. A Belgian officer even ran into our sixth company four days ago. If I had lost my sense of direction while fetching food, I would have had to shoot myself, because I would never have found my way out. In some places you get fire from four sides and finding the right direction is a real feat, I can tell you that. After I've had another taste of war, I'm already sick of it again. The greatest joy is always the mail. Now we're in barracks. Wonderful wooden barracks, almost like in Döberitz. The houses in the village are not usable because they are totally shot up, and now the shells are still whizzing into the ground. Greetings Alex

Zandvoorde, 20 January 1915: All you dear ones at home! You will have been surprised by the abrupy ending of my previous letter. The mail was just about to be picked up and in order to get back to you as soon as possible, I sent it off without having finished writing it. I'm sure you were also astonished at our life out there in the trenches. But don't imagine it to be like that everywhere. This is the only cosy spot in front of Ypres. Every day, and again just now, we are surprised that the battery next to us is firing so wildly, and as we come out of our barracks we hear cries of 'Hooray'. We can imagine that there's an attack going on somewhere nearby. And this is not very cosy. To our left was the 8th company and they have 10 dead and 14 wounded to mourn. Dear little Lotte! In your letter you again and again express the confidence that we will see each other again. I hope so too, but as long as we continue to be at war, I don't know if I'll get out of it in one piece, but there will be other times. Let's hope that everything works out then too. Hopefully that Herr Kalischke you write about will find me, but you have to give me the company of the person in question when you do things like that, otherwise it's so difficult to find anyone. How is Uncle? He hasn't written to me for a long time. But I am surprised that you did not notice the loss of the lace that was included in letter number 18, the lace was 10 cm wide. Is there any point at all in my continuing to number the letters? Likewise, you do not seem to have received letter number 34. And dear Adolf! You can't fool me with the chocolate. When I have some, I eat six bars a day without spoiling my stomach or allowing them to fill me up. Occasionally you can send me cheese or herring butter. I will close for today, as I still have a lot of writing to do. Greetings from your son and brother Alex and hope to see you again soon. PS: Please excuse the poor writing, but the table is occupied by the 'gentlemen' NCOs while we, the common soldiers, have to be content with using their wallets as a table. Please send a copying pen in a case, have lost all of mine. All the best wishes and a hundred kisses, Alex.

Menin, 22 January 1915: All my dear ones at home. You must really feel I don't think of you any more, or that I have grown lazy about writing. Neither is the case! The first is already logically impossible and the latter, well, I had received so many cards and letters from other people, all of which needed to be answered. In Zandvoorde, our alert quarters, we mended the roads and when we had time off, the only place where there was light was occupied by the 'gentlemen' non-commissioned officers and I can't outside write in the rain. When we arrived here, I stood on battalion watch. That was a punishment, because I made fun of Münke. But now we are friends again. And you can imagine how tired I was. Especially since we only slept four hours last night, and then marched through what remained of it. In the morning I cleaned the lice out of my quarters, in which men of the 136th regiment were billeted during our absence, and in the morning I went straight on guard duty, and slept only four hours that night. In the afternoon I went to the cinema. To regain my strength, I had a German rump steak roasted and ate it with relish. Today the one-year volunteer officer candidates were promoted to Leutnants. But you know, our Rittmeister is a splendid fellow. I drank schnapps for once! Cheers! Oh, I shouldn't have told you that! Gave away the secret! But never mind, a big sip of schnapps in the trenches does you good and warms you up. Dear father, you write to me that my dear mother can't fit enough into the parcels. Even if you are right about the enormous weight of the backpacks, nothing will perish, and in the end, my back is strong enough to carry the burden. It doesn't even need to be supported by an Iron Cross! I've never been weak, even on the forced marches through Belgium in the early days, when the others were falling by the hundreds. So they'll soon want to get at you too, dear Adolf. Damn you civilisation, where have you gone? Well, March is still a long way off. If it's going to take that long, the work should be done by then. They've started an offensive at Soisson. Our soldiers are heroes, bigger than those of 1870! You should see the enemy's entrenchments. Barbed wire obstacles and then three trenches, one behind the other. Ours look the same! And when you've captured the first position, then you have to wade through knee-deep mud. An incredible job has been done there! But the losses! An English machine gun like that, firing 600 rounds a minute, is effective! I can tell you that! Even during exercises it happened that comrades got stuck up to their necks in the mud. When they came out, they had to leave their boots there and come back later on socks to dig them out. And everyone who tried to help them got stuck too, which was quite funny. Would really be something for the cinema. In Zandvoorde I went to see our 21-cm howitzers. Just seeing them is a spectacle! But they are not as huge as you see in paintings. But how incredible they are when they are being fired! I know what it means to get heavy calibres into one’s trench and I can't help feeling sorry for the poor French. The gunners didn't paint 'Terror of the French' on the huge barrel for nothing. The barrel hammers back, and then majestically rolls forward again! The whole gun, even when the tail is dug nice and deep into the earth, hammers back half a metre and buries itself even deeper in the soil. Of course, it has to be aimed anew each time, which is very hard work. Four men push the shell into the barrel with a rod, and after the sixth shot the French artillery acknowledges in kind! I marvelled at how well the French or English aimed. Right over our heads, but 300 metres too far! The gunners ducked low! I can't really describe these impressions to you in writing. That would be a doctoral thesis! I only wish that I could tell you all about it in person later. Let's hope for a reunion. I could have told you that this would happen to Jahnke, good merchant soul that he is. Gefreiter - Feldwebel - officer - Iron Cross - rheumatism - and back home he is. That is the usual career of such gentlemen. I have experienced more than one of these cases. Now I must finish. with many thousand warm greetings and hot kisses Alex.

Menin, 26 January 1915: Dear parents and brothers and sisters! I did not want to write today, but the parcel that arrived unexpectedly prompted me to immediately lodge a complaint. Now that the age of chocolate has ended, the age of lard is obviously beginning. Do you have any idea how much lard I have now? At least 2 kilos. I can't avoid calling for assistance as I can't possibly eat all that alone. And hold off on the cigars, too. I have over 50 of those alone now! And then there are the cigarettes. So I don't even get to use my beloved pipe any more, and that even though I now have a good tool to clean and load it with. I thank the uncle again for that. So please send all such things in future only on request! You probably didn't know that one can get fat during war either. Today I had to shave off my 4-month-old classical beard and my God, how fat my cheeks have become. Can you believe it? Now say again, that I will never put any weight on, I'll laugh out loud into your faces from now on. And tomorrow we'll have free German beer and Frankfurter sausages. Hurray! Long live our Kaiser Wilhelm! Although it's not his fault that he was born. Dear parents, I didn't really want to ask you for money, but I can't manage here with my 5.30 Marks. Can't you send me 2 Marks? I'm always very thirsty here, even though I drink so much lemonade. Dear Adolf! So you wish the Yser Canal at our backs. Believe me, I've had it at my back once and that's enough for the rest of my life. Things are different behind the front. Here the Lys has overflowed its banks and completely flooded the country. The river has swollen enormously. In some places, only the treetops look out of the water. So Eugen is now a proud prisoner of war? I wonder if he still has such a big mouth now. I would be very interested. And Herman, Emilia's husband, is in the English camp in Ruhleben? What's going on!?! The world has become crazy. Tomorrow, 50 Iron Crosses will be distributed in the battalion. Our paymaster (!!!!!!!!!!!!!) has received the Iron Cross, probably for brave behaviour in the provisions room! Well, maybe I'll be in for one too! Hooray! I want to go for a glass of beer with some comrades, in an inn where three (pretty) French women are serving. The French girls all have classical, little feet, which they know how to expose coquettishly. Best regards from your son and brother, Alex.

Menin, 28 January 1915: So we celebrated the Emperor's birthday in a dignified, very dignified manner. On 26 evening there was a military tattoo by six bands, I am sure they must have heard the drums in Ypres. From 4 o'clock we celebrated in a monastery, with two barrels of Patzenhofer beer, then we had Berliner Buletten, which unfortunately didn't stay long in our stomachs, but came out with the superfluous beer with the rest of the vomit - and all this in a monastery in front of the nuns! now i'm diligently collecting wool, it's getting cold here. So far I have relied on my white woollen blanket which i've conquered in Diksmuide, probably a Ghurka blanket. It is very warm but also very heavy when i have it in my knapsack. Do me a favour and buy the Illustrierte from the 17th and the war special number 24. If I should come back, these sheets will be a nice reminder of our achievements. It's really touching how Julia takes care of me, so many lovely things she has sent and now the slippers! I am very grateful to her for this. It has been freezing really hard here and the mighty effeminate French are walking around with red noses and two scarves wrapped around their heads and necks. But that is no reason not to send me woollen things. Unfortunately my old scarf has been lost and that is why I would like to ask you to send me a new one. Furthermore a shaving brush and some sugar. Nothing else is on my mind. Very warm regards from your son and brother Alex.

Menin, January 29, 1915: All of you, my dear! The herring butter was once again a real surprise. In any case, I am very well supplied for the time being. We will be spending time in the trenches. This afternoon at 3:15 we will be leaving; not immediately to our positions, but first into the alert quarters. The 143rd regiment is said to have made a successful attack and we will probably take over their positions. We may then have a counterattack to repel. Well, then, we'll have experienced everything the war has to offer. Let's hope that I will be able to give you news in a few days and greetings from your son, brother Alex.

On 30 January, the regiment's last front-line action took place during its stay in Menin. This time at a more southerly front of the Ypres Arc, not far from Hollebeke, where IR 143 was relieved. In the afternoon of that day the regiment marched over Wervique and Comines to Kortewilde. The II and III Battalions took up positions from there to the front. The condition of the positions here was even worse than usual. The sandbag coverings were often insufficient and were regularly penetrated by rifle bullets. At the beginning of February, the French enemy was replaced by British troops. On 31 January, Infantry Regiment No. 99 made a partial attack on the enemy trenches, unleashing heavy retaliatory fire that caused the 201st Regiment losses of 7 killed and 41 wounded.

During their stay, the men of RIR 201 took Menin and its inhabitants to their hearts. The regimental history supplements the experiences of Alexander Stranz:

Most of the inhabitants of Menin were Flemish, i.e. of Low German descent; therefore we were able to get along with them reasonably well. But it was precisely the Flemings who - in contrast to the French - initially received us rather unfriendly. While the French inhabitants of Halluin met us with a friendly attitude (which is by no means always synonymous with kindness!), the Flemings were cold and frosty; only later, when they had got to know us better, did they become more receptive. Menin was not a 'beautiful' city; its buildings lacked the characteristics of a finer culture. Not even the town hall with its belfry could lay claim to artistic taste. Nevertheless, we still like to look at the pictures of Menin, because they take us back to the beautiful times spent there (...) The living room in Menin was almost always something in between a kitchen and a parlour; its tiled floor, the fireplace with its mostly tasteless frippery under glass lintels, the high-backed woven chairs all seemed a little strange to us. Equally strange to us was the low, iron stove, which, with its long and wide exhaust pipe, served as a heating device, cooking machine and clothes dryer. In the cold days, it was the centre around which we sat down to chat with our hosts. As soon as we entered, the friendly Flemish housewife asked: "A bit of coffee?", and of course we did not refuse such a friendly offer. After all, in every household there was always a large pot of coffee to keep warm on the stove top. Our conversations, in which our wives sometimes addressed us as 'Soldatske', but more often by our first names and called us by our first names, were mostly about the war, but also about domestic and economic circumstances. We learned all kinds of things about the life of this people, who are related to us by blood, but under whose roof the fate of war has sent us as 'enemies'.

With few exceptions, Menin's population was still resident in the village in the spring of 1915. Where there had been industry, bleaching and weaving before the war, the remaining male population was mostly without employment, smoking home-grown tobacco in their nose-warmers, demonstrating astonishing skills in spitting, sitting for hours in the Estaminet, the 'Volksfriend' or the 'Harmonie' over sour beer or a glass of anisette. Here and there you could still find old women in the houses making lace, and many of their pretty works were bought by our field graves and sent home. The graceful daughters of our landlords' families were a little bashful at first, but as time went on, they became more and more friendly, and in the end they were not at all unwilling to chat with their 'Fritz' or 'Willi', and even learned a few words of German.

But it was the adolescents who felt most at home, as they were always on holiday. Most of the time they loitered in the streets and squares. Since the boys from eight to twelve were already passionate cigarette smokers, but were now suffering from a severe shortage of supplies during the war, it very often happened that such a tiny tot turned to one of our fieldgreys with a: 'm'sieur - cigarette?’ A request which, after the man had recovered from his astonishment, was usually granted.

Kortewilde, 4 February 1915: My loved ones! Last night they shot my best comrade and friend. Do you know what it means to lose the one with whom you have gone through everything side by side until now? It's like a wagon without a wheel! We were standing together and talking when, at one point, a bullet goes through the sandbag and grazes his head! A little further down and he wouldn't be there. Thank God it's only a splintered bone, but he'll be away from the company for four to six weeks, and who knows if I'll still be there. So on the 30th at 5 o'clock we left and arrived at our reserve position at 8 o'clock. On the very first day the 99ers made an attack, you should have heard the shooting. They were over at the enemy in no time at all and took three machine guns and six prisoners. Our losses: five dead. Now the enemy feared the attack would continue and sparked into our trenches and there our 6th Company had 16 dead and wounded! The 99ers had the success and we had the dead. First they wanted to straighten the line and then they had to fear that the trench was undermined. And I don't know which is better, being shot in the attack or being blown up. And now, during the night, the French wanted to retake the position eight times with 'hurrah', but they are beaten back with just as much 'hurrah'. However, our first attack seems to have taken them completely by surprise, because they didn't even fire their three machine guns. On the second, third and fourth night they gave up trying. If you haven't seen such trench systems, you can't even imagine it. It is like a small town, but the houses are not built upwards, but downwards. Because of all the water, a proper sewer system has been built and even the pumps are not missing. Signposts are everywhere: 'To the 143rd Regiment', 'Towards the 8th Subsection', 'Battalion Staff II/201', 'Villa zum feuchten Rattenloch' (Villa to the wet rat hole), etc. What our pioneers have achieved is tremendous! However, asphalt roads are hard to find here. On planks you walk man after man. One misstep and you're up to your knees in water! In some places, the path is really not that ideal, as you have to walk through tough mud. And me, I see how the person in front of me falls and suddenly I'm sitting in the mud too! Well, I tell you, you have no choice but to shout loudly for help. And if no helping hand approaches you, you're hopelessly lost! Because you can't get out of such a mess on your own! It's straight up like playing Cowboy and Redskins, and you'd enjoy it if bullets weren't constantly whizzing over your head, reminding you of the seriousness of the situation! But when you're always bent over with a heavy backpack on your back and a rifle in your hand, you're so exhausted! And the path at the end! This is hilly terrain! All of a sudden, when you've crested the hilltop, you're going down again! Then it goes 'boom!', 'whoosh!', 'crash!' and shrapnel bursts overhead! But because they come regularly, you don't really notice them. Then all of a sudden someone shouts 'Fire' and then it goes 'Boom, boom, boom'. And our batteries fire overhead. You get a bigger fright than when the enemy shrapnel bursts overhead. At least I saw the church spires of Ypres! Right in front of us! We were at Hill 59, to the left of Hill 60! A large church, all shot up, was also visible. It must have been a wonderful building once. The position wasn't so bad. I don't think there's another one like it in front of the whole of Ypres. There were about three of us together and the atmosphere was quite relaxed. Unfortunately, it was over when my friend was wounded! The French were always shooting at our embrasures and when it got too much for us, three of our groups concentrated their fire on a French iron shield and dented the thing so badly that there was a hole in it! It was a real prize shoot! But then I saw that I could still hit something! Well, you have to get used to shooting again first. In any case, I came back safe and sound. Tomorrow my platoon will probably be on pioneer duty. It's going to be pretty exhausting, but also very varied. If everything goes well, we'll be back in Menin the night after tomorrow. Before I forget, if you would now see me with my helmet on , you wouldn't think I'm a volunteer grenadier, but a volunteer fireman! Because I have modernised myself and unscrewed the helmet spike! Much to Münke's annoyance! This minute I received the latest card from you and frankly it didn't pleasantly surprise me that it's finally your turn Adolf. Dear little Lotte, I thought for a long time that you would complain about my silence regarding the shipments. As long as I don't write anything, they are always to my utter satisfaction and praiseworthy. But now please send me the finest sandpaper! What for, I am not allowed to tell you as a soldier! Soap and milk more often! Enough for today, if there is time tomorrow, a second letter will follow, until then, greetings and kisses from your son, brother and now comrade, Alex.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to THE IRON TIME to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.